Earlier today, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in challenges to two of the Biden administration’s higher-profile efforts to end the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first case, National Federation of Independent Business v. Department of Labor, an array of well-heeled business groups, conservative organizations, and red-state governments challenged the administration’s rule that requires private employers to implement either a vaccine mandate or, for unvaccinated employees, a testing-and-masking policy in the workplace. In the second, Biden v. Missouri, red states objected to a separate vaccine mandate for employees of health care providers—hospitals, clinics, and so on.

Despite the radical right-wing leanings of this 6-3 Court, the administration has at least a chance of prevailing in the healthcare provider case. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked skeptical questions of the state challengers at oral argument, suggesting that they might join their three liberal colleagues and vote to uphold the rule.

The good news stops there. The conservative justices appear eager to strike down the vaccine-or-test mandate, which covers an estimated 84 million people. This result would do more than hobble the nation’s already-insufficient response to COVID-19. It would also advance the conservative legal movement’s decades-long campaign to kneecap the federal government’s ability to effectively address other unfolding crises.

The Biden administration’s authority to require basic public-health measures in the workplace is crystal-clear. In a statute passed in 1970, Congress required the Occupational Health and Safety Administration to issue an “emergency temporary standard” regulating workplace conditions when the agency determines that such a standard is “necessary” to protect employees from a “grave danger” resulting from exposure to “physically harmful” “new hazards.” The agency promulgated the vaccine-or-test rule last year after examining data and evidence on the dangers of COVID-19 in the workplace, and the efficacy of vaccines, masking, and testing. As it turns out, a contagious disease that has killed more than 800,000 Americans and is entering its third year counts as a “grave danger.”

That should be the end of the case: Congress authorized a particular category of agency action, and the agency reasonably invoked that power to regulate employers commensurate with the danger their employees face. But for the right-wing justices, when an agency takes action to address an especially important problem—for example, a deadly pandemic—an ordinary congressional grant of authority is not enough. Rather, Congress must have specifically anticipated that problem and explicitly authorized the agency to take that particular measure to address it.

At oral argument, the conservatives repeatedly invoked this expansive made-up rule, which is known in legal circles as the “major questions doctrine.” Roberts asked Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who argued in defense of the vaccine-or-test mandate, to confirm that mandating vaccine coverage is “something that the federal government has never done before.” He also remarked that he didn’t think that Congress “had COVID in mind” in 1970, when it passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act, and observed that 1970 “was almost closer to the Spanish Flu than it is to today’s problem.” The Chief Justice didn’t expand on why Congress’s inability to predict the onset of COVID-19 five decades ago is evidence that Congress wouldn’t have wanted the government empowered to do anything about it.

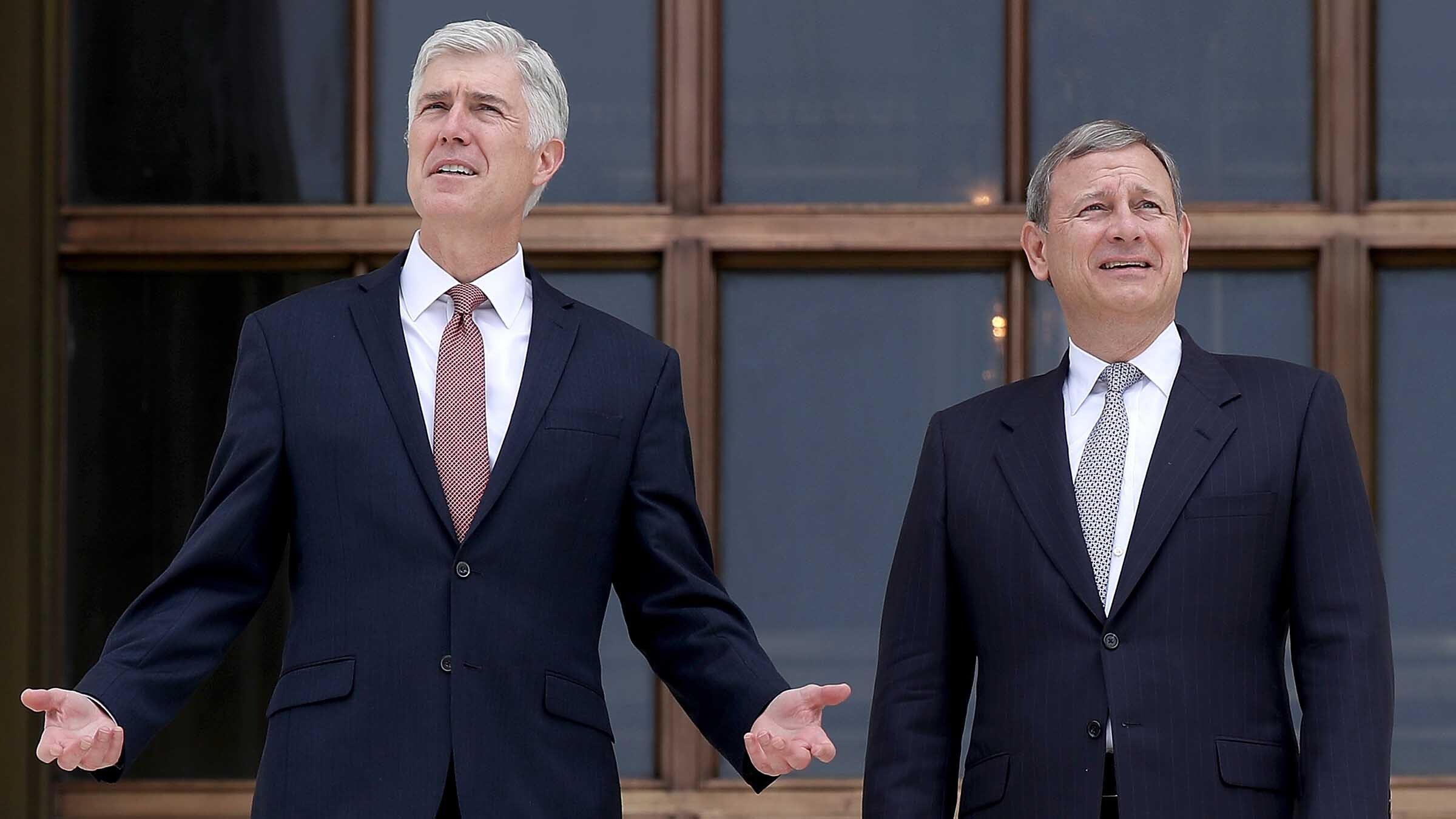

Pictured: Neil Gorsuch and John Roberts encountering a new idea (Getty Images)

Other conservatives followed the Chief’s lead on Friday, ignoring Justice Elena Kagan’s (correct) rejoinder that it makes no sense to declare a vaccine-or-test mandate unlawful simply because it’s “kind of a big deal.” Justice Samuel Alito complained that the mandate is “different from anything OSHA has done before.” Justice Neil Gorsuch agreed with Chief Justice Robert’s point that the statute is “50 years old” and “doesn’t address the question” of whether a vaccine-or-test mandate is permissible. The source of Gorsuch’s implicit assertion that statutes carry less force once they pass the half-century mark remains unclear.

The justices’ questions suggest an absurd conclusion: that because OSHA has never imposed a vaccine-or-test mandate in response to a pandemic before, it can’t do so now. Instead, Congress must pass a brand-new law specifically authorizing OSHA to protect employees from the spread of disease—maybe specifically from COVID-19—in the workplace. As Prelogar pointed out, such a rule would be brand new. It would also place decades of agency rules on suddenly-shaky ground. What the conservative justices want to do, apparently, is require that Congress magically foresee every possible measure that would be necessary to address future emergencies, and then spell out the authorization for those measures in painstaking detail in the U.S. Code.

Conservative justices have hinted at a similar anti-novelty logic in other contexts. In 2020, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Seila Law v. CFPB invalidating the single-director structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a decade-old independent agency that Republicans had consistently attacked as a freedom-trampling job killer. Roberts wrote that because no executive branch agency had previously been designed precisely like the CFPB—with one director, removable by the president only for good cause—the Bureau was “an innovation with no foothold in history or tradition.” This logic is the jurisprudential equivalent of being skeptical of cars because you’ve only ever seen horses and buggies before. Kagan mocked it in her dissent, writing that “novelty is not the test of constitutionality when it comes to structuring agencies.”

This morning’s arguments suggest that the Court is eager to expand that anti-novelty rule against agency innovation into the vaccine-or-testing mandate context. And where the Senate’s retention of the filibuster stymies even a Democratic-controlled Congress from passing almost any legislation, that rule would be a death knell for the federal government’s ability to protect workers from COVID-19. Even more alarmingly, it would imperil countless other rules passed under decades-old statutes intended to confront modern problems—like the EPA’s regulation of greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act. (After all, Congress probably wasn’t thinking about carbon dioxide when it conceived of “air pollutants” in 1970.)

The Court’s ongoing dismantling of the administrative state is a deliberate process. At a moment when conservatives are likely to control the Court for at least a generation, they don’t need to win congressional or presidential elections to ensure a perpetual veto over federal policy; the Court’s power to scrap lifesaving vaccine mandates is just one example. That’s why conservatives fought so hard to control the federal courts in the first place: When life-tenured judges are making the choices, reactionary politics are suddenly a lot harder to stop.