Tremane Wood was scheduled to be executed at 10 AM today as punishment for a murder he did not commit. At 9:59, Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt instructed the Oklahoma Department of Corrections to call it off. Stitt commuted the death sentence, and Tremane will spend the rest of his life in prison.

On December 31, 2001, Wood, together with his brother and their girlfriends, participated in the robbery of Ronnie Wipf and Arnold Kleinsasser at a motel in Oklahoma City. In the course of the robbery, Wipf was killed by a single stab wound to the chest. Wood and the others were all charged a week later with one count each of felony murder, robbery, and conspiracy to commit robbery. For the brothers, prosecutors sought the death penalty.

The Oklahoma Indigent Defense System could not represent both of the Wood brothers due to conflict-of-interest restrictions. So one brother, Jake, got the state’s experienced team of capital defense lawyers and investigators. Tremane got a court-appointed private attorney in the throes of various personal crises, including alcohol addiction and substance abuse. Tremane’s attorney did virtually no work on the case, gave no opening statement, and would have called no witnesses if not for Jake’s startling mid-trial confession: He was the one who stabbed Wipf.

Prosecutors contended that Jake was lying to save his little brother, and suggested that Tremane would do the same thing during Jake’s trial. The jury sentenced Jake Wood to life in prison, and Tremane Wood to death.

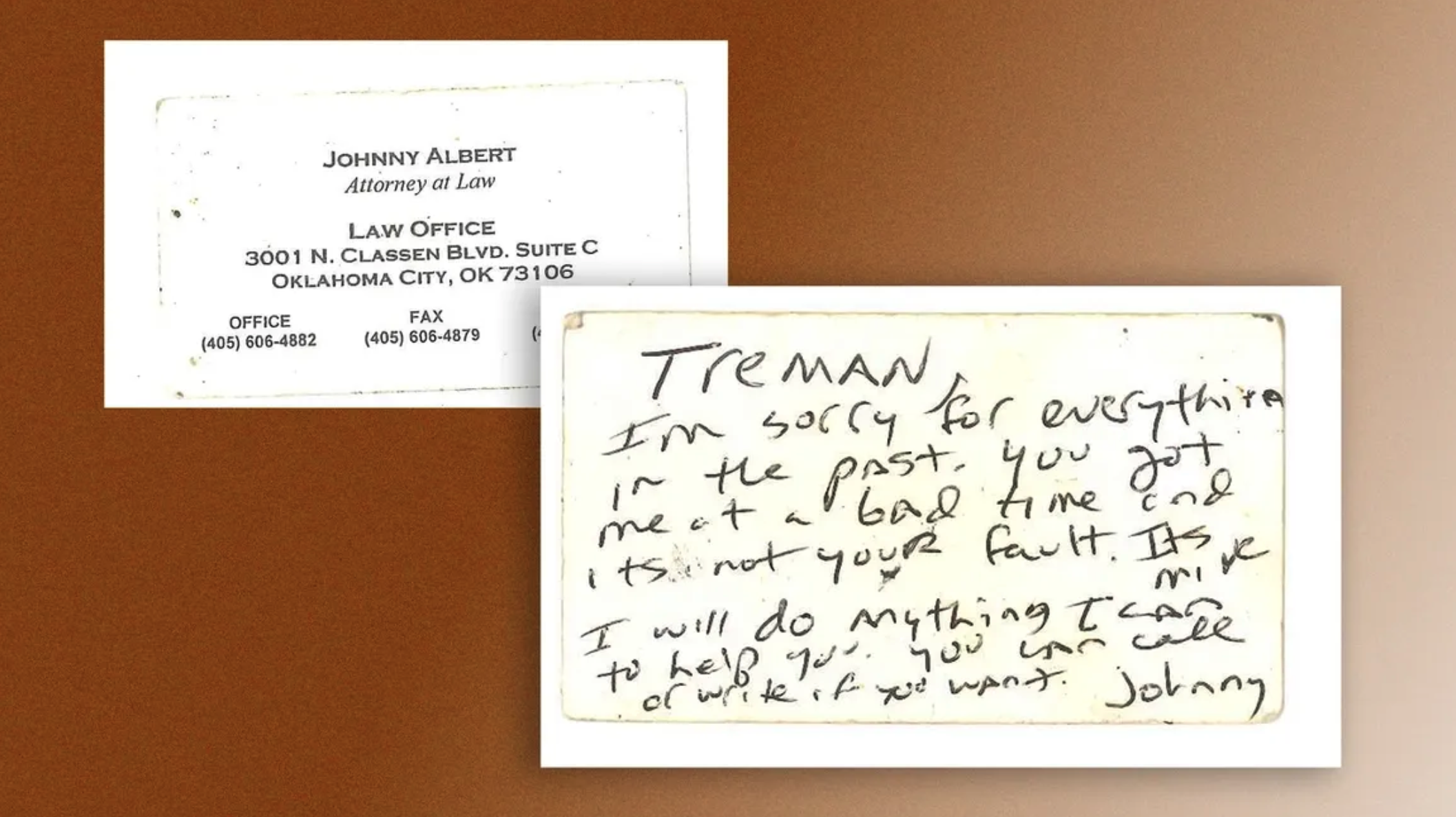

Later, Tremane’s counsel sent him an apology note on the back of a business card, reading, “You got me at a bad time, and it’s not your fault. It’s mine.” Tremane also learned, decades after the trial, that the prosecutors struck secret deals with his ex-girlfriend and another witness to testify against him in exchange for dramatic reductions in their prison sentences. Prosecutors also allowed them to lie on the stand about whether such agreements existed.

Image via Tremane Wood Foundation

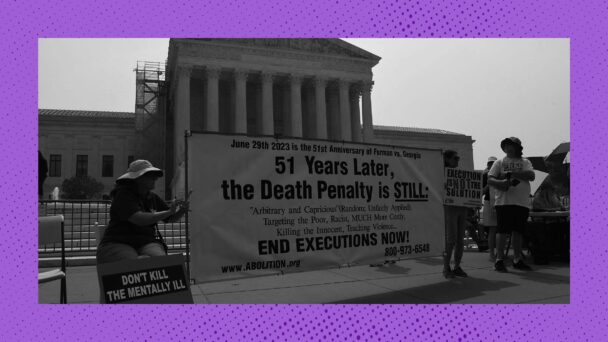

In light of the myriad failures at trial, a majority of the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted last week to recommend clemency in Wood’s case. After the state announced its plans to move forward anyway, Wood petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to stay his execution and take up his appeal. His attorneys argued that this case is no different from another recent Supreme Court decision, Glossip v. Oklahoma. There, too, Oklahoma prosecutors suppressed evidence related to the credibility of a co-defendant who testified against a defendant who was sentenced to death.

Mere months ago, the Court held that this violated Richard Glossip’s constitutional right to a fair trial. Yet on the morning of Wood’s scheduled execution, the Court denied both of his requests without explanation. Only Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson noted her dissent.

The Supreme Court is often the last possible backstop to pause or outright prevent state-sponsored killing—a power it permits to go to waste. In 2023, the Court received 158 requests from people sentenced to death, asking for review of their constitutional claims or a stay of execution, and granted only 4. The 2024 statistics are similar: 148 death row requests, only 3 granted. This year, the Court has not granted a single request to postpone an execution. Stitt’s acceptance of the state parole board’s recommendation in Wood’s case is only Stitt’s second grant of commutation in his seven years in office.

On Thursday evening, hours after the state was supposed to kill him, Wood was rushed to a hospital after officials found him unresponsive in his cell. He was stabilized shortly after his arrival, and was able to speak with his family and spiritual advisor. Doctors determined that his condition was likely the result of “dehydration and stress.”

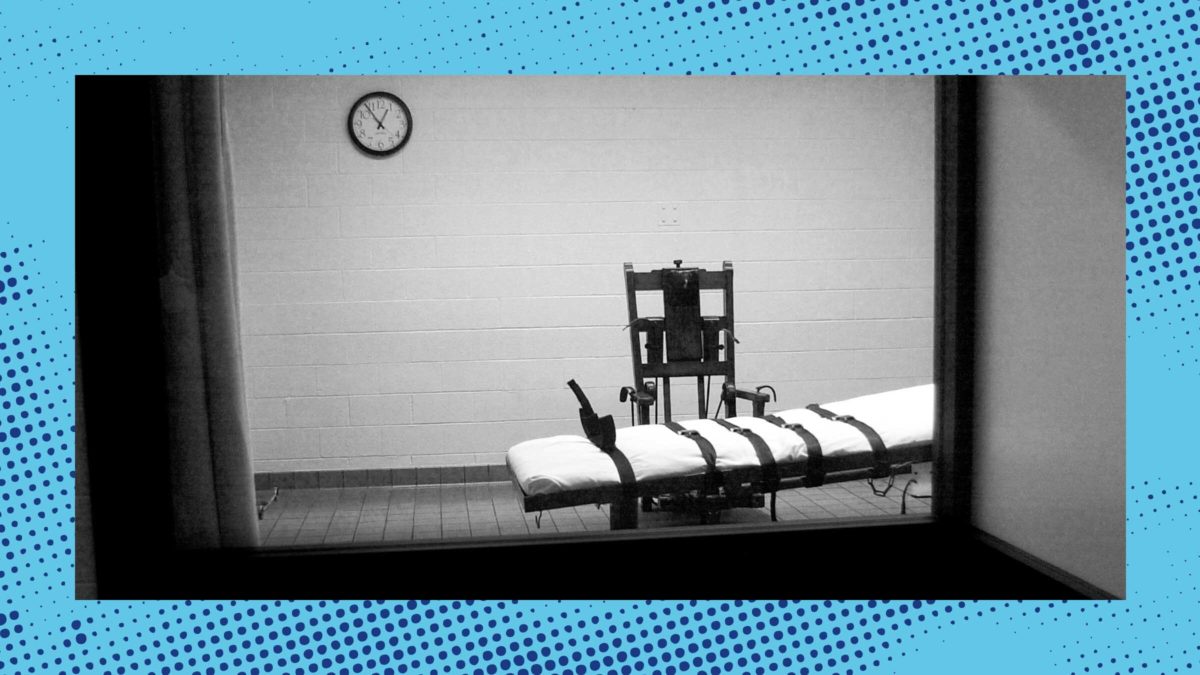

In 1972, the Supreme Court found that dozens of state death penalty statutes violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment, effectively making capital punishment unconstitutional in much of the country. The Court backtracked four years later, but continued to struggle with the issue; in 1994, after decades of voting to uphold the death penalty, Justice Harry Blackmun famously declared that it suffered from “inherent constitutional deficiencies” that could not be cured, and said that he would no longer “tinker with the machinery of death.” Today’s Court makes no such promise.