It was around 1:00 AM on a November night when William Wooden heard someone knocking on his door. He wasn’t expecting anyone in particular, given the late hour. Plus, there was the weather, which was rough that night. Temperatures in Madisonville, a town of about 5,000 people nestled near the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Tennessee, tend to be pretty mild that time of year. But in 2014, Monroe County was enduring a cold spell, and outside of the single-wide mobile home Wooden shared with his wife, Janet Harris, the air hovered around freezing.

Wooden opened the door anyway, where he found a stranger named Conway Mason standing on his porch. Mason was an investigator with the Monroe County Sheriff’s Department, but Wooden couldn’t have known that from looking at him, since Mason wasn’t wearing his uniform and his car was unmarked. Nor did Wooden realize that the deputy wasn’t alone—there were two other uniformed cops standing out of sight. They’d later claim they were there looking for a “fugitive” named Brian Harrelson.

What happened next is disputed. Both Wooden and Mason agree that Mason asked to speak to Janet, and both agree that Wooden said he’d go inside and get her. But, right around the moment that would change the trajectory of the rest of Wooden’s life, their stories start to diverge. The officer claims he asked to come inside because it was cold, and says Wooden consented to his entry. Wooden says that neither the ask nor the consent happened. Either way, as Wooden walked down the hall away from the officers, Mason and another deputy entered the house without a warrant. Only then did they notice that Wooden was holding a rifle.

The officers yelled for Wooden to drop the weapon and the uniformed officer drew his gun. Wooden obeyed, but it was already too late. “I said, ‘Aren’t you a convicted felon?’ […] and he said he was,” Mason testified later. They handcuffed Wooden and patted him down, where they found another gun in a holster.

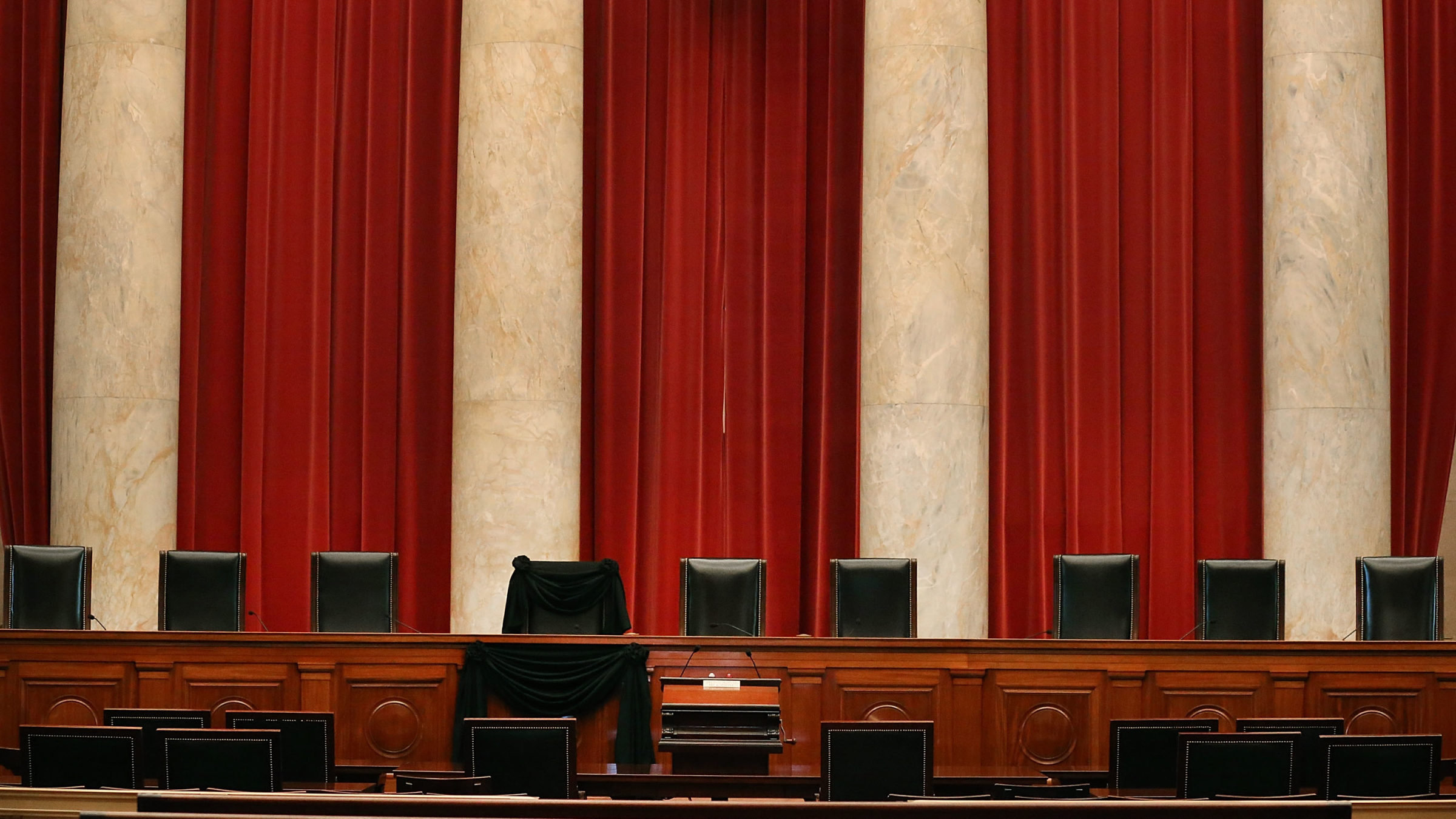

The cops never did find Harrelson that night, but when they searched the house they found plenty of other things: another rifle, drug paraphernalia, plus Janet and a few others hanging out in a back room. And while Wooden wasn’t the only one who was arrested, he ended up paying the biggest price, in a winding and chaotic legal case that epitomized the arbitrariness of American criminal law even before yesterday, when it made its way before the justices of the United States Supreme Court.

The short version of what happened after that night is this: Wooden was charged in state court, but the case was dismissed within days, and he figured the whole thing was over. A few months later, however, federal prosecutors came after him: He was charged with, tried for, and convicted of being a felon in possession of a gun. Before his sentencing, prosecutors argued that Wooden’s previous convictions—more on that soon—qualified him as a career criminal under the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA). As a result, instead of the recommended two-year sentence he would otherwise have faced, Wooden received a mandatory minimum of fifteen years. Today, Wooden is spending his sixth year locked up in a federal prison in Arkansas. He’ll be 65 when he’s scheduled for release.

Wooden appealed his sentence on a number of grounds. He argued that Mason entered his house without permission and without a warrant, violating his Fourth Amendment rights. He argued that even if he had consented to Mason’s entry, because Mason had dressed in plain clothes and arrived in an unmarked vehicle, he used deception to gain access to the home—a constitutionally-protected area—by claiming he just wanted to stay warm. Lastly, Wooden argued that he did not qualify as a career criminal under the ACCA, a sentence-enhancing statute that kicks in after at least three “violent felony” or “serious drug” convictions that were “committed on occasions different from one another.”

The Supreme Court agreed to hear his case, but only to address that very narrow final question. Back in 1997—some seventeen years before Conway Mason knocked on his door—Wooden and three others had broken into a mini-storage facility in Georgia. While inside the building, they entered ten different storage units. Nearly two decades later, after his arrest in Tennessee, federal prosecutors argued that each of those entries into each unit was a different “occasion,” and that that night’s burglary in Georgia should count as ten separate offenses under the ACCA. Wooden, of course, says they were committed on the same “occasion”—his entry into the mini-storage facility—and should count as a single offense.

Because the ACCA is triggered by repeat convictions, for Wooden, the resolution of this technical-sounding question makes all the difference in the world: If the government is right, his record is lengthy enough to trigger the ACCA’s mandatory minimums. If he’s right, it isn’t. “Were these burglaries committed ‘on occasions different from one another’?” his lawyers ask in a brief filed with the Court. “Fifteen years in federal prison depends on the answer.”

Yesterday’s oral argument—an hour-plus of the highest court in the land attempting to suss out the precise definition of the phrase “occasion”—was a textualist fever dream. In briefs filed with the Court, Wooden’s counsel argued that an “occasion” means under the “same circumstances” or resulting from the same “criminal opportunity”—a single “criminal episode.” Whether a given sequence of events qualifies, his lawyers conceded at oral argument, is “admittedly” a “context-specific” determination.

Meanwhile, the government’s counsel, Erica Ross, argued for the harshest possible definition that more or less dispensed with context altogether: If “one offense is over before the next begins, then the two are committed on different occasions,” she argued. Ross added that such an approach has the “benefits of administrability”—that is, it makes it easier for prosecutors to lock people up for the maximum amount of time.

If you’ve ever listened to a Supreme Court oral argument, you will be unsurprised to hear that the justices immediately embarked on a meandering journey of hypotheticals. Justice Clarence Thomas wanted to know whether an “occasion” is the same opportunity if someone takes a smoke break in between crimes. Justice Samuel Alito wondered if a mugger who waits by a broken street light and mugs passers-by at 10:00 PM, 11:00 PM, and midnight took advantage of “one criminal opportunity or three.” Chief Justice John Roberts followed up asking if the answer would be different were it a moonless night instead.

Not to be outdone, Justice Elena Kagan asked about a “multitasking” crime boss using multiple phones to arrange drug sales, run an illegal gambling operation, and arrange a hit on a rival. “They’re all going on very close in time to each other,” Kagan said. “Single occasion or three occasions?”

The conversation predictably devolved into the sort of absurdity that is near-guaranteed when we count on vague statutory terms to dictate outcomes without reference to human judgment. “Let’s say you’re a newspaper reporter and you’re trying to write a story about what happened here,” an incredulous-sounding Kagan asked Ross. “I mean, would you ever say something like ‘the facility storage units were burglarized on ten occasions’?” If Ross recognized that her definition failed a basic test of common sense, she didn’t show it. “I think you could say—you might well say they broke through drywall on ten occasions,” she said. “You know, there are ways to think about that.”

That several justices seemed uncomfortable with the government’s argument was a relief, sure. Yet the focus on the precise definition of a single word, as it so often does, obscures rather than illuminates what’s happening here. The ACCA claims to target “career criminals.” It’s absurd, then, to claim a person who breaks into ten different storage units in one night should qualify. But it took until well into Ross’s argument for a justice to articulate that fundamental point. “If the only criminal activity by this defendant his entire life had been the burglaries of this warehouse,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked, and “20 years later…he commits another criminal activity, do you think the layperson would believe that this person was a ‘career criminal’?”

The need for such a myopic analysis of the word “occasion” yesterday can be partially blamed on the failure of the ACCA itself. Writing for SCOTUSBlog in February, John Elwood called the ACCA a “‘three strikes’-type sentencing enhancement whose legendary ambiguity has spawned so much litigation that…it can sometimes seem as if there are more Armed Career Criminal Act appeals than there are armed career criminals.” It is a sentencing relic of the Reagan administration, harkening back to the early stages of modern mass incarceration when lawmakers eagerly signed their names to the cruelest legislation they could think up. Both the ACCA’s harsh punishments and thoughtless ambiguity are reflective of a Congress that has long been preoccupied by political opportunity rather than long-term reflection.

Still, zeroing in on the definition of a single term is also a tool of convenience for the Court, because it perpetuates the fantasy of a functional system—of pretending that the arbitrariness in the criminal legal process can be rooted out through honing in on the correct legislative term. This obscures the rot at the core of a system that is almost as inconsistent as it is cruel. Here, the definition of “occasion” is only one sliver of the arbitrariness threaded throughout Wooden’s case, from the moment Mason knocked on his door. Remember, back in 2014, the local prosecutor decided not to charge him at all. How is that reconcilable with a fifteen-year federal prison sentence, dictated by the definition of “occasion”? If we were really attempting to address arbitrariness, that feels like a good place to start.

The most powerful actors in the legal system remain more concerned with how an individual should be punished than with how a system should be changed.

I keep thinking, too, about the night the cops knocked on Wooden’s door, trying to make some sense of it. But like countless other disputed incidents with law enforcement, this one doesn’t really add up. Why were these cops looking for Brian Harrelson at Wooden’s house at 1:00 AM? In court, Mason claimed it was because he “had seen [Harrelson’s] vehicle at the residence […] within [the past] few days.” But Harrelson’s car wasn’t there the night Mason knocked on the door. Most importantly, if they had suspected for days that Harrelson was in the residence, why didn’t they get a search warrant?

Which leads to another question that keeps nagging at me: Why were three cops out looking for Harrelson at all? You hear the word “fugitive” and think of Harrison Ford jumping off a dam to escape Tommy Lee Jones. But Harrelson was a fugitive in a much more technical sense—he was wanted for a simple misdemeanor theft charge.

There are more fundamental questions I have, too, about the system as it is and how we want it to be. Why is burglarizing a storage facility with no one inside considered a violent felony? Regardless of how we define “occasion,” should merely holding a gun be enough to transform someone into a career criminal? And why is the government not only justifying the cruelty of a law like the ACCA, but strenuously arguing before the Supreme Court that it should be construed as harshly as possible?

Most of these are questions the Supreme Court can’t address, and others are questions they won’t. Instead, they’ve done what the Court does best—dilute the real-life repercussions of a system that relies on violations of people’s rights, narrowing their concerns into the most basic and technical form. Given the extraordinary arbitrariness that arose at each stage of this case, it is in the Court’s best interests to now pretend that the only variable that matters when it comes to William Wooden’s future is the meaning of the word “occasion.”

This is why the story of what happened to Wooden, even though it has no bearing on the specific question the Court is considering, matters here: What the courts don’t consider worthy of analysis tells us as much as what they do. Wooden’s ordeal illustrates so many of the inhumanities that plague the criminal legal system, and how ill-equipped the courts are to rectify them. Part of that is by design, but the reticence of individual judges plays a significant role, too. The most powerful actors in the legal system remain more concerned with how an individual should be punished than with how a system should be changed.

Both simple logic and basic humanity would dictate that Wooden prevails in this case. But even if he does, the vast majority of the institutional faults that led him here remain unscathed. Once again, courts prioritize regulating civilians over regulating the state, insisting that individual people pay for systemic failures—not only failures of law but also failures of enforcement, and not just the arbitrariness of language but also the arbitrariness of process.