As a co-host of 5-4, a podcast about how much the Supreme Court sucks, Rhiannon Hamam spends an inordinate amount of time reading some of the most ghoulish, morally bankrupt gibberish that nine life-tenured fancy lawyers could ever come up with. This summer for Balls & Strikes, she’s returning to a dozen of the worst cases she’s been unable to get out of her head, despite her fondest wishes and best efforts, to see how all the awful shit the Court is doing today intersects with all the awful shit it’s done before. This is Wild Pitches, a column that will remind you that saying that the Court is “bad” right now does not mean that it was ever “good” in the first place.

Republican Bob McDonnell won Virginia’s gubernatorial election in 2009 and took office in January 2010. His campaign slogan was “Bob’s for Jobs.” First, I want to point out that it is incredibly easy to make campaign yard signs for the white suburbs. “Let’s rhyme something with Bob!” Second, I want to highlight a bit of dramatic irony, which is that while Bob promised to create jobs, he was pretty bad at doing his.

To be specific, Bob was bad at budgeting and finance. When he took office, McDonnell and his wife Maureen had nearly $100,000 in credit card debt and an estimated $1.5 million in debt in multiple Virgina Beach properties they owned through a real estate firm. The McDonnells desperately needed money to continue presenting the image of a successful and astute family in the public eye, and to avoid personal bankruptcy.

Enter sugar daddy. In 2009, Bob McDonnell met Jonnie Williams, the CEO of Star Scientific, when Williams offered up his private jet for McDonnell’s campaign travel. At that time, Williams had just begun to pivot Star Scientific from a company that sold confounding tobacco products of questionable efficacy—like “tobacco lozenges”—to one that peddled dubious dietary supplements and cosmetics made from tobacco derivatives. (Gonna propose a better name for the company: Not So Scientific.)

Williams was trying to find ways to boost his company’s profile. He knew that if a research university were to announce a trial launch of his new supplement, Anatabloc, their involvement would confer some badly-needed legitimacy on the company (and, probably, a healthy stock bump). So in October 2010, Williams asked McDonnell for help. McDonnell agreed to introduce Williams to Virginia’s Secretary of Health and Human Resources, Dr. William Hazel. Soon after, Bob’s wife Maureen asked Williams to buy her an Oscar de la Renta gown to attend a political event; in exchange, she promised Williams a seat next to the governor at the event. On a later occasion, over dinner at the governor’s mansion, Bob, Maureen, and Williams talked about the proposed studies.

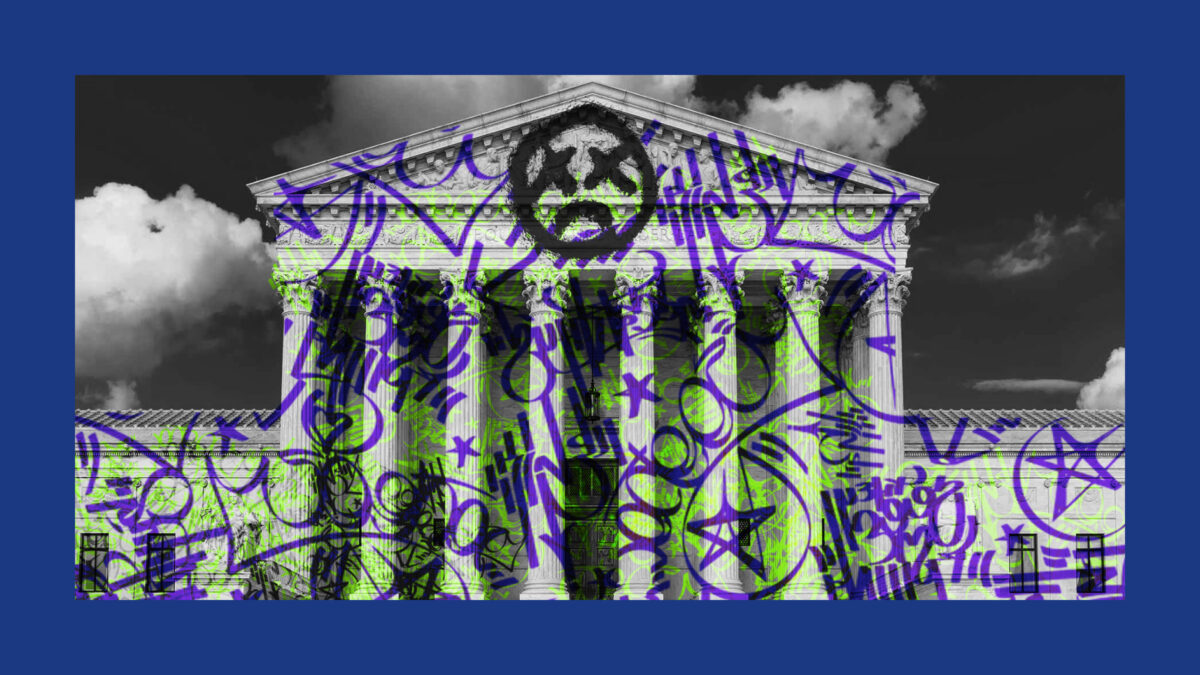

(Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

Both Williams and the McDonnells realized how helpful they could be to one another. The McDonnells hosted a launch event for Anatabloc at the governor’s mansion with state researchers from Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Virginia, where Jonnie Williams handed out eight $25,000 checks for researchers to use in preparing grant proposals. Meanwhile, Maureen McDonnell asked Williams for a $50,000 loan to address the financial stress of the family’s real estate investments; according to charging documents, Williams agreed to lend the money, and told the governor that “loan paperwork was not necessary.”

Bob McDonnell, meanwhile, set up more meetings for Williams with state agencies, and asked a state official to “reach out to the Anatabloc people and meet with them.” Then came a $15,000 gift from Williams to cover catering costs at the McDonnells’ daughter’s wedding. Williams also offered the McDonnells a stay at his vacation home—and, when Maureen asked for it, access to his Ferrari during their getaway, too.

This is the politician version of 2Chainz saying he would be “fresh as hell if the feds watching,” because the feds were indeed watching! A week after McDonnell’s term ended and they moved out of the governor’s mansion, federal prosecutors charged them in a 14-count indictment that included allegations of “honest services” fraud, bribery, and corruption. At trial, a jury found both McDonnells guilty; Bob was sentenced to two years in prison, and Maureen a year and a day. Of course, they appealed, and of course (because powerful people live by different rules), the judge did not require their incarceration as the case made its way through the appellate process.

Under the criminal law at issue here, the prosecution needed to show that Bob McDonnell had committed (or planned to commit) an “official act” in exchange for the loans and gifts from Williams. An “official act” is defined as “any decision or action on any question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy, which may at any time be pending, or which may by law be brought before any public official.” Put plainly, the legal question is whether Bob McDonnell committed “any action” on the matter of Anatabloc research in exchange for $175,000 in loans and gifts.

When you’re trying to describe to your friends how big the catered spread was at your daughter’s wedding (Photo by Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Pause for temperature check! How do we feel? I mean, I’m no federal prosecutor, but I feel like this is a slam dunk case for the government! While Williams handed over tens of thousands of dollars in loans and showered Bob and Maureen McDonnell with gifts, Bob was setting up meetings, hosting events, and networking with government officials about Anatabloc research.

And yet! A fully unanimous Supreme Court said, Hold up, what if this was actually normal and fine? In an opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Court held that McDonnell’s actions designed to help initiate the research studies were not, in fact, actions designed to help initiate the research studies. “Setting up a meeting, hosting an event, or calling an official (or agreeing to do so) merely to talk about a research study or to gather additional information…does not qualify as a decision or action on the pending question of whether to initiate the study,” Roberts wrote.

In fact, Roberts continued, public officials’ freedom to take these actions is actually what representative government is all about. “The basic compact underlying representative government,” he wrote, “assumes that public officials will hear from their constituents and act appropriately on their concerns—whether it is the union official worried about a plant closing or the homeowners who wonder why it took five days to restore power to their neighborhood after a storm.” If we allow Bob McDonnell to be prosecuted for taking $175,000 in loans and gifts from a weirdo pharmaceutical CEO in exchange for encouraging state research on the product the CEO sells, then according to Roberts, We As A Society would be opening the floodgates to potentially prosecute the government official whom those “homeowners invited…on their annual outing to the ballgame.”

Something I’ve learned over three years of analyzing these garbage Supreme Court opinions every week, and which I believe will likely be a theme throughout this series, is that when you are reading one, you should ask yourself at the end of every page, “Does this make any sense at all?” A legal culture of judicial supremacy and deference to the Court has put legal media and academia in the concerning position of just accepting everything these robed dipshits say at face value.

You do not have to do this. You are a human being who lives in the world. You know better. Say it with me: These people are lying to us, and they are wrong.

“Corruption? Illegal?? Well now I’ve heard everything!!” (Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

Take the utter nonsense Roberts passes off as analysis here. McDonnell setting up meetings and hosting events for Anatabloc in his capacity as Governor of Virginia simply “don’t qualify” as actions on the question of Anatabloc research, according to the Chief Justice. There is no compelling reason offered in the entire opinion for why this is the case; there is only John Roberts and his vibes asserting that the actions “don’t qualify.” And miss me with the comparisons to the humble constituent bringing their concerns to a responsive elected official. A governor shilling for a snake oil CEO in exchange for $175,000 in loans and gifts is not the same as a public official responding to the concerns of “a union official worried about a plant closing.” In all of the silly and reductive parallels Roberts draws to idyllic channels of communication between public officials and constituents, there is no personal financial gain to the public official. The constituents aren’t paying the public officials for their time and energy and actions on the matters they bring up. Mister Chief Justice, we are comparing apples and Oscar de la Renta here.

Beyond how insulting it is to be told that, legally speaking, actions aren’t actions, McDonnell came with predictable consequences for public corruption cases. A recorded phone call in which an elected representative agrees to propose legislation on a matter in direct exchange for a cash gift, or a written contract where a businessman and a mayor agree to direct terms of a quid pro quo—no one does that, because public officials know that those actions are illegal. An accountability mechanism that only functions in the context of smoking-gun evidence of bribery encourages public officials and the monied interests who seek to influence them to game the system. Politicians are allowed, by the language of the ruling, to stop just short of direct political action and avoid committing formally illegal acts, but are more or less permitted to tiptoe (in very expensive shoes) as close to that line as possible without worrying about charges of corruption.

McDonnell also exposes a much bigger problem in American government than Roberts would ever admit. The Roberts Court has long approached public corruption cases with skepticism: In 2020, it overturned convictions of two defendants involved in the “Bridgegate” scandal in New Jersey, and just this term, it overturned public fraud convictions of a construction business owner contracting with the government, and for a former government official taking illicit payments to benefit a developer. All three of these decisions, like McDonnell, were unanimous.

The Court’s habit of beating statutory language to death in service of the most technical and narrow interpretation of “corruption” imaginable obfuscates the purpose of laws that target public corruption in the first place. The justices could, for example, acknowledge the massive influence money has in our politics—the flow of money and favors exchanging hands in government offices, and the corresponding erosion of public trust in the very idea of representative government. Instead, they tie themselves in linguistic and intellectual knots to reach the conclusion that these scandals—these betrayals of the public duty and trust—are technically not “real” illegal activity.

And on whose behalf? When you read a case like McDonnell, you realize the inevitability of Clarence Thomas getting wined, dined, yachted, flown out, and generally spoiled by adoring billionaires. You understand why the Republican defenses of his actions focus almost exclusively on whether there was a technical, formal violation of existing law: This kind of behavior has so permeated our system of government, from city councils to Capitol Hill, that Supreme Court justices simply do not see the problem. In fact, they are a part of it.

As a former public defender, I can assure you that the judiciary’s meticulous skepticism of public corruption laws does not apply to other criminal statutes. All too often, the Court is willing to sweep a broad range of behavior into the scope of criminal laws, if it means a poor person gets convicted and punished.

The powerful and wealthy live by different rules, though. In our system, one of the most immediate benefits of attaining political power is entry to rooms full of people who have money and want your attention. Aggressive enforcement of public corruption laws would mean stripping away that juicy benefit of political power. The McDonnell decision pulls back the curtain on an ugly world in which corruption is so normalized that Supreme Court justices will look away—as if their family real estate deals, their luxury vacations, and their billionaire cosplay depend on it.