Depressing legal question: is there a constitutional remedy available when a Border Patrol agent shoots an innocent child for no reason? I would hope the answer is yes, personally. But in Hernandez v. Mesa, the Court’s answer to that depressing legal question is a resounding no. I would like to live in a world where our purported legal protections from police officers violently wilding out actually mean something, a world where the law provides for meaningful accountability so that if a police officer violently wilds out, there is meaningful legal redress. There are, after all, multiple amendments in the Bill of Rights written to protect individuals from police overreach, misconduct, and excessive use of force–not least of which is the Fourth Amendment, which bans police from unreasonably searching or seizing anyone. When the police violate those rights, I would like to live in a world where they would be held to account. Alas we are in this world. This is a world where the Supreme Court has made up every possible reason to bar victims of police violence from justice, including by completely disallowing a lawsuit against a violent officer to be filed at all.

On June 7, 2010, fifteen-year-old Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca was shot dead by Border Patrol Agent Jesus Mesa at the Paso del Norte Bridge, the border area that connects El Paso, Texas, with Cuidad Juárez, Mexico. Hernández, a Mexican citizen, had been playing a game with friends under the bridge at the border, running up the embankment on the American side, touching the border fence, and running back across the border into Mexican territory. Kids played this game often, and their activities were familiar to Border Patrol agents. Even though the children posed no risk to border security, Agent Mesa interrupted the game and detained one of Hernández’s friends on the United States side of the border. Hernández and the other kids ran back into Mexico, but even having technically crossed the border and standing in Mexican territory, they remained a mere 60 feet away from Mesa, who was still in the U.S. Agent Mesa claimed that the children began throwing rocks at him, but cellphone footage of the incident indicated that was not true. Whether reacting to kids throwing rocks, or kids playing, or kids running away, Mesa took perhaps the most depraved and disturbing course of action available to him: he aimed his weapon and fired at least two shots across the border at the group of children. Hernández was struck in the face and died.

Hernández’s parents filed a lawsuit against Mesa in federal court in the United States. Their claim was that Mesa’s use of excessive force (shooting their child in cold blood) had violated Sergio Hernández’s Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights, and that a 1972 case called Bivens entitled them to sue for damages to remedy that constitutional violation. The Bivens case established an important accountability mechanism for rogue federal officers in the law, but by the time the Hernandez case made it to the Supreme Court nearly four decades later, a conservative majority was no longer interested in protecting that remedy.

Attorney Bob Hilliard represented the family of Mexican teenager Sergio Adrian Hernandez Guereca (MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images)

In Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics Agents, the Supreme Court held that the Constitution implicitly guarantees the ability of an individual to file a lawsuit for money damages against federal law enforcement officers when they violate constitutional rights. In that case, federal agents raided Webster Bivens’ home without a warrant, manacled him in front of his wife and children, searched the home, and arrested him without basis. The Supreme Court ruled that Bivens could sue the agents for their illegal actions, which violated his Fourth Amendment rights against unreasonable search and seizure. In situations where asking for an injunction wouldn’t address the harm already done, and the government itself can claim immunity from a lawsuit that is based on the misconduct of its officers, the Bivens case stands for the proposition that an individual can pursue a claim for money damages against the federal actors who violated her constitutional rights. A Bivens claim, as these lawsuits are now known, ensures a legal pathway to redress where no others exist.

But in a deeply unfortunate turn of events for the Hernández family, and any of us who could be constitutionally harmed by federal officials (every single one of us [sobbing]), conservatives on the Supreme Court have been stomping out the applicability of Bivens since the 1980s. Even though Bivens stated boldly that federal courts should use any remedies “to make good the wrong done” by rogue federal officers, Republican-appointed judges have consistently ruled that a Bivens lawsuit can only proceed when the underlying facts giving rise to the suit closely mirror the facts and legal context of Bivens itself. Shamefully, writing for a five-justice majority in 2020, Justice Pennywise (née Samuel Alito) held that Sergio Hernández’s parents did not have a cause of action to sue Agent Mesa, because the case was too different from Bivens.

The majority’s ruling rests solely on the fact that Sergio Hernández was on the Mexico side of the border when he was shot. Even though Agent Mesa was in the United States when he fired his gun, and was acting under the authority of the U.S. government, Alito hollowly announces that the “international” nature of the case means that the lawsuit arose in a “new context” than Bivens. A cross-border shooting is “meaningfully different,” according to the opinion, from federal law enforcement officers violating the rights of someone who is physically in the United States. But hold up Samuel. Slow your roll. There are multiple reasons why Hernández’s technical location in Mexico when he was shot, mere yards from the United States, is actually irrelevant. Mesa’s misconduct–shooting a gun at innocent children as a law enforcement officer for the United States government–occurred on U.S. soil. Further, U.S. law governs Mesa’s conduct and the harm he causes. Plus, the Hernández family could almost certainly sue under Bivens if their son had been standing on the U.S. side of the border, just a few feet from where he was killed–if this had all occurred in Houston, or Seattle, or sixty feet from where it actually happened, Sergio Hernandez’s family could sue Agent Mesa. The child’s position in Mexico is the only reason given by the majority for why the Bivens claim cannot proceed. Alito says that because the bullet happened to collide with Hernández’s body on Mexican soil, there can be no lawsuit to hold that officer to account.

Justice Pennywise (née Samuel Alito) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Worth emphasizing: this ruling had nothing to do with whether Agent Mesa violated this child’s constitutional rights by murdering him at the U.S.-Mexico border. The Court ruled that it simply doesn’t matter whether he did or not; regardless of what the Constitution might say about Mesa’s actions, the Hernández family couldn’t even sue Mesa in the first place. Having found nonsensically that the context of Sergio Hernández’s death (federal officer’s misconduct violates the Fourth Amendment) was too different from the context of Webster Bivens’ injuries (federal officers’ misconduct violates the Fourth Amendment), Alito moves on to considering whether any “special circumstances” surrounding the cross-border shooting would also justify closing the courthouse door on the Hernández family. Here’s where Sammy boy really slides into his intolerable bumbling era. Apparently, allowing the Hernándezes’ lawsuit to proceed would impact the foreign relations of the United States, undermine security at the U.S.-Mexico border, and would mean that the judiciary had overstepped its role where the executive branch should be acting.

It’s every damn excuse in the book, and it’s important to remember when reading this opinion that the red-string-board international relations lecture isn’t legal analysis. The majority asserts that one “special circumstance” counseling against allowing a cause of action here is that allowing the cause of action would impact U.S.-Mexico relations, of course with no specific references to how, exactly, that would happen. Importantly, there’s no consideration in the opinion that disallowing a cause of action, as they do, would also impact U.S.-Mexico relations. Deciding that Agent Mesa can’t be held liable in this way isn’t any less of a foreign policy decision than holding that he can be. The same goes for Alito’s pontificating about the potential impact on border security that a Bivens claim could have in this context. The facts of Sergio Hernandez’s death may entail matters of border security (in that a federal officer tasked with ensuring border security shot and killed a child at the border), but the Court deciding there is no legal claim has no less of an impact on border security than deciding that there is one. I’m not even convinced that there would be an impact on foreign relations or border security by deciding the case either way–after all, what we’re talking about is the rogue actions of a single officer who acted unlawfully. Holding that there is a pathway to legal accountability for that misconduct is not some massive transformation in the terms and conditions of international diplomacy.

The Supreme Court, according to Alito, shouldn’t make foreign policy decisions that are properly within the power of the executive branch. But this is a legal question before the Court, not a question of foreign policy. The matter before Alito and his robed cronies is whether there is a constitutional remedy available for when a Border Patrol agent shoots a child dead. That is not a question that the executive branch can answer. The president of the United States cannot decide that a family has a cognizable legal claim in federal court for which they can recover damages. That’s YOUR job, Samuel, you goblin freak.

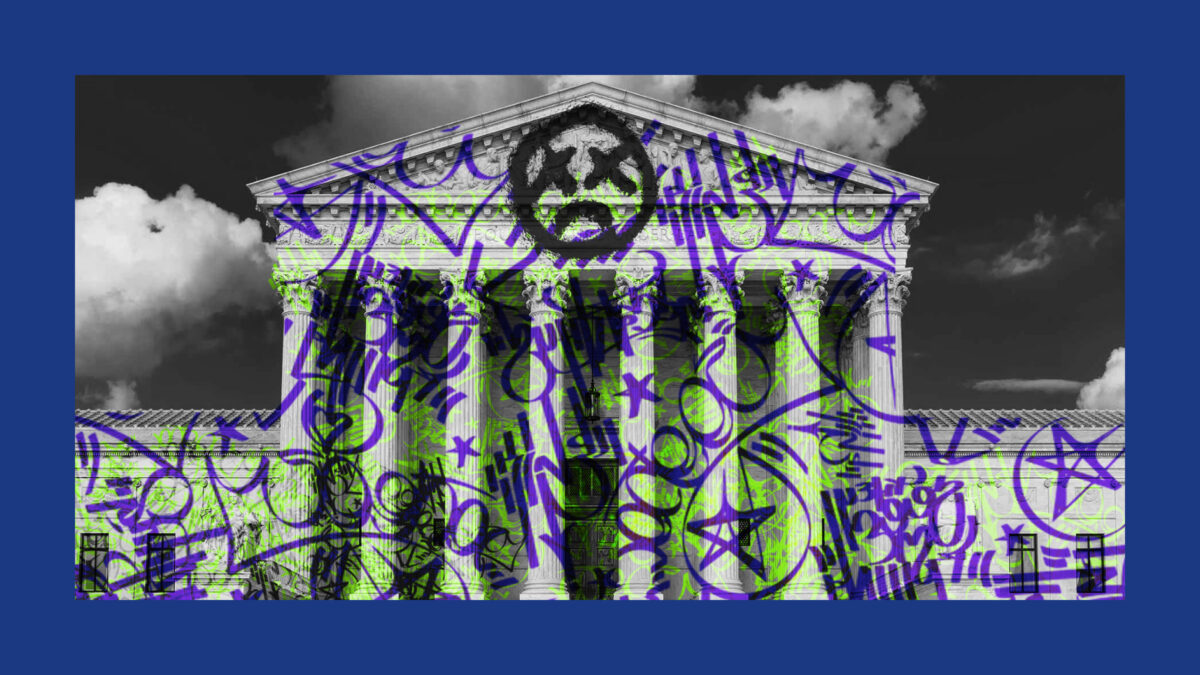

While decrying judicial policymaking in Hernandez v. Mesa, the conservative majority’s policy preferences are laid bare: they simply do not want victims of police violence to be able to sue for damages. That desired outcome is couched in a nonsensical policy lecture in which the conservatives suppose there could be an impact on foreign relations and border security by finding for the Hernández family, and conveniently, that potential abstracted impact is disfavored by them. To launder their policy preferences into objective legal analysis, they disregard and obscure the fact that deciding the case against the Hernández family as they do reciprocally implicates those same policy matters. This is the fake neutrality that the conservative legal movement thrives in. Ruling that a cross-border shooting gives rise to a “new context,” that is “meaningfully different” from other circumstances where a lawsuit could proceed, and that “special circumstances” like “foreign relations” also indicate that this lawsuit cannot proceed–these are not neutral, objective legal conclusions. Conservative Supreme Court justices pick and choose the legal outcomes they prefer behind the smoke screens of judicial restraint, separation of powers, and formalistic legal rules. In the context of Bivens claims, this means the ability to vindicate your constitutional rights against federal officers is so restricted over time that it becomes nearly meaningless. A child was shot and killed by a federal officer, and the Supreme Court says the Constitution doesn’t have a remedy for that.

Meaningful legal remedies are critical to a legal system ostensibly based on individual rights. The Constitution enumerates certain rights–through the First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendments, for example–to establish a system of laws oriented towards the protection of individual liberty. But what does a list of your rights mean if you can’t address the harm done when those rights are violated? Abstract “rights” are meaningless if there is no legal remedy for when a right is taken away. By its terms, the Fourth Amendment protects us from excessive force by police. But for Sergio Hernández, the Fourth Amendment was a hollow pronouncement. By holding that his family had no legal avenue to sue the officer who murdered him, the Supreme Court closed the door on any substantive accountability mechanism for redressing the violation of Hernández’s rights, thereby calling into question what those rights materially ever meant in the first place. The case is disturbing for its revelation of an American legal reality: to a Supreme Court justice, constitutional rights can just be words on paper.