When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last year in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Court’s conservatives tried to couch the decision in moderated, legalistic terms.

In his majority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito wrote that the Court was simply returning the power to regulate abortion “to the people’s elected representatives.” Justice Brett Kavanaugh filed a platitude-ridden concurrence stating that “on the issue of abortion, the Constitution is neither pro-life nor pro-choice. The Constitution is neutral.” Both justices were making the same point. They were claiming that the decision did not speak to the propriety of abortion, but instead was a judgment only about the scope of the Constitution.

But if you looked just slightly closer, you could see a moral reasoning underneath that formalistic veneer. The majority referred to doctors who perform abortions as “abortionists,” a popular term among anti-choice activists, and gave credence to vague claims that sonogram technology had made abortion less palatable. Kavanaugh alluded to the idea that abortion impacts a “potential life” as a key component of his decision.

The conservative legal movement and the anti-choice political movement were always telling two different stories about abortion. If you heard the lawyers tell it, it was a matter of constitutional technicality: There is no right to abortion implicit in the Fourteenth Amendment, so states are free to ban the practice. To the broader anti-choice movement, however, this wasn’t about the balance of state and federal power—it was about stopping the mass murder of unborn babies.

The briefs submitted in Dobbs highlighted the dichotomy. While the parties themselves focused primarily on the narrow questions of whether a federal right to abortion can be read into the Constitution and how much weight to give to stare decisis, conservative organizations filed inflammatory amicus briefs framing abortion as a great moral crisis. Students for Life of America argued that “abortion’s human death toll causes unsustainable population decline” and that abortion serves “eugenicist goals.” The Pacific Justice Institute compared the treatment of fetuses to that of antebellum slaves (“fetuses, when aborted, are treated as slaves of their mothers and put in the most severe involuntary servitude.”) An array of organizations filed briefs arguing that fetuses should be considered legal persons under the Fourteenth Amendment—an outcome that would ban abortion nationwide. One of those briefs, signed by dozens of anti-choice organizations and state legislators, included more citations to the Bible than the Constitution.

The tension between the apocalyptic rhetoric of anti-choice activists and the calculated legalese of the right-wing legal movement made the conservative position hard to parse at a glance. Credulous journalists and academics acted as if there were simply two different groups of conservatives with distinct sets of principles. But the reality is that they are two cogs in a singular machine, serving separate functions but a shared purpose: the elimination of legal abortion.

(Photo by KENA BETANCUR/AFP via Getty Images)

A few years ago, that may have been a controversial statement. Conservative legal organizations like the Federalist Society have held themselves out as distinctly nonpartisan, committed only to a narrow set of legal principles. Their concern with Roe v. Wade was, according to them, not born of political opposition to abortion, but of their adherence to a narrow view of the Fourteenth Amendment. (The group is notoriously cagey about their views, publicly claiming only that they were founded to ensure “that the principles of limited government embodied in our Constitution receive a fair hearing.”)

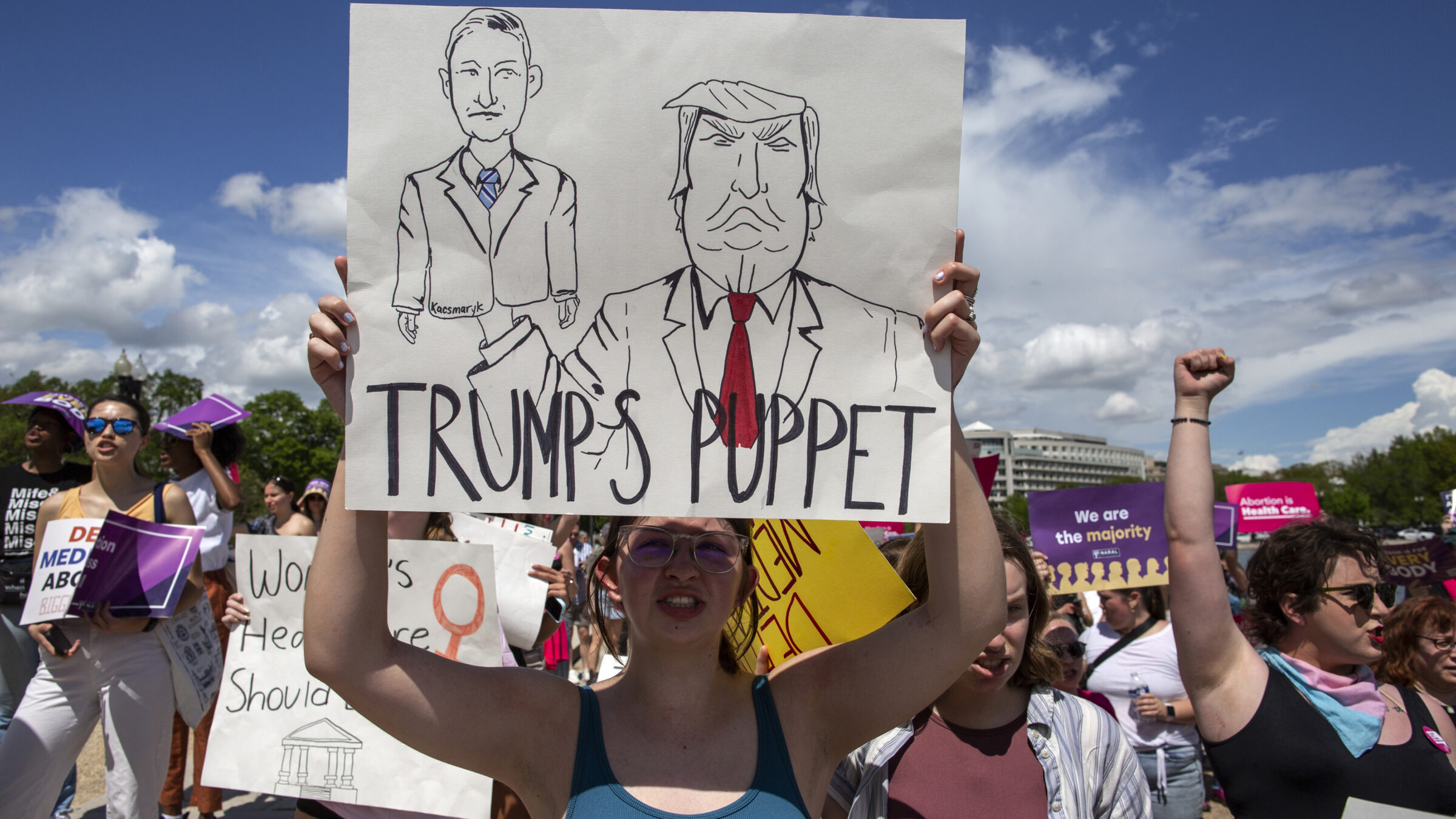

But if that were true, their mission would have been complete after Dobbs. Instead, Republican judges have continued to press the matter. This April, Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, a Trump-appointed federal judge in the Northern District of Texas, attempted to nullify the over two-decade-old FDA approval of the abortion-inducing drug mifepristone. His decision wasn’t predicated on the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment or any other tangible legal principle. It was a transparent attempt to limit access to abortion, so brazen that it shocked even savvy legal analysts. (Kate Shaw, a professor at Cardozo Law School, called the ruling a “travesty”). Moreover, a panel of judges on the ultraconservative Fifth Circuit upheld much of the ruling, testing the limits of the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority. Over the rambling objections of Alito, the Court ultimately stayed the lower court order, keeping mifepristone available at least pending the outcome of further litigation.

The mifepristone case is part of the second phase of the conservative legal movement’s anti-abortion crusade. During the first phase, while their focus was on overturning Roe, the legal movement shied away from the heated rhetoric of anti-choice activists because it was incongruent with their insistence that this was a matter of jurisprudential technicality. Now, however, their interests are more closely aligned, and the lawyers are free to drop the facade. While they once cast doubt on efforts to protect abortion at the federal level by questioning Congress’s ability to regulate abortion at all, they are now calling for a federal abortion ban. While they once predicated their opposition to Roe on the purportedly narrow scope of the Fourteenth Amendment, they are strategizing to use a broad interpretation of the same provision to forbid abortion nationwide.

An abortion rights activist holds a sign with a sketch of Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk and former president Donald Trump (Photo by Probal Rashid/LightRocket via Getty Images)

To a doctrinalist—a liberal legal academic, for instance, focused on jurisprudence rather than political context—this might come across as hypocrisy. But “hypocrisy” doesn’t quite capture the spirit of the conservative effort. It’s not hypocrisy when a mugger asks you for the time to get you to pause before he mugs you. You don’t wonder afterwards why the mugger lost his interest in the hour once you handed over your wallet. It was a simple ploy, laid bare as soon as he pulled out the gun. Conservatives discussing states’ rights and the scope of substantive due process weren’t trying to engage you in a good faith academic debate. They were just asking you for the time.

A year after Dobbs, it may not be particularly insightful to point out that opposition to Roe, even among lawyers, was driven by barely-disguised anti-choice animus. But many liberals’ reactions to Kacsmaryk’s mifepristone decision show that they may not have fully absorbed the lesson. In the days following, Democratic politicians called the decision “lawless.” What they meant is that it was untethered by the usual formalities of legal analysis. But law is not a mode of analysis, it is a fact of power. Yes, Kacsmaryk’s ruling was ludicrous, devoid of any rational throughline. But it was not “lawless,” it was quite literally the law. It was the law because the law is, ultimately, whatever judges say it is, and Kacsmaryk is a judge because conservatives have seeded the judiciary with their political allies.

This isn’t an academic point. Politicians and journalists and lawyers talking about “lawlessness” are, implicitly or not, yearning to return to a halcyon era when judges adhered to rules and norms rather than their personal political preferences. But law is and has always been a reflection of the institutions that define it. When American politics were less polarized and courts were more ideologically balanced, formalism and moderation were the primary modes of legal analysis. Now, our politics are dominated by extremists, and reactionaries control the courts. The trappings of moderation have limited appeal and diminishing utility for reactionary judges. This doesn’t mean that law has fundamentally changed, only that its aesthetics are evolving.

It’s a political imperative that Democrats and liberals adjust to this new paradigm. To date, many senior Democrats have carried on hoping that adhering to old norms will somehow resuscitate them. Dick Durbin, the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, has refused to subpoena Justice Clarence Thomas (or anyone else) over an array of ethical concerns. Senate Democrats have maintained the practice of “blue slips,” which give Senators veto power over judicial appointments in their state, and has functioned to disproportionately impede Democratic nominees. And Democrats have largely refused to embrace substantial judicial reforms like Court expansion, leaving control of the judiciary in right-wing hands for the foreseeable future.

All of this together signals a type of intransigence, an unwillingness to accept that the judiciary is part of the modern political battlefield. Republicans leveraged it to eradicate reproductive rights, and Democrats must leverage it if they want to win them back.

The debate over Roe v. Wade was never a doctrinal dispute. It was a proxy war fought through legal doctrines. Conservatives didn’t win it through superior jurisprudence; they won it by commandeering the federal judiciary and bending the law to their will.

Liberals need to understand that the coming fights over reproductive rights won’t be won through doctrine, either. They will be won through acquiring and leveraging power. That means winning elections, yes. But it also means, at the very least, holding the judiciary accountable, eliminating blue slips, and seriously entertaining court reform. Without that, you’re left trying to have an academic discussion with people who think reproductive freedom is genocide.