In his last days as president, Donald Trump was getting desperate. After losing the 2020 election in decisive fashion, he began pushing baseless conspiracy theories that the results were tainted by voter fraud, and ordered his Department of Justice to open sham investigations of crimes against democracy that did not take place. As the date for certifying the results approached, he began organizing slates of illegitimate electors, and pressured Republican state officials to send those slates to Washington instead. When that effort fizzled out, Trump ordered Vice President Mike Pence to set aside the results during the formal vote count; when Pence balked, Trump turned to his enraged supporters outside the White House, urging them to “fight like hell.” They responded by ransacking the U.S. Capitol, leading to the deaths of nine people.

On Monday, in its final ruling of the 2023-24 term, the Supreme Court decided that none of this, legally speaking, matters. Writing for all six members of the Court’s Republican supermajority, Chief Justice John Roberts invented a sweeping doctrine of presidential immunity that broadly insulates Trump from prosecution for his actions leading up to January 6. The result in Trump v. United States also ensures that if Trump wins a second term this fall, he will be free to exercise the now-near-boundless powers of the office without fear of meaningful consequences.

“The relationship between the president and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably,” writes Justice Sonia Sotomayor in a dissent joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. “In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law.”

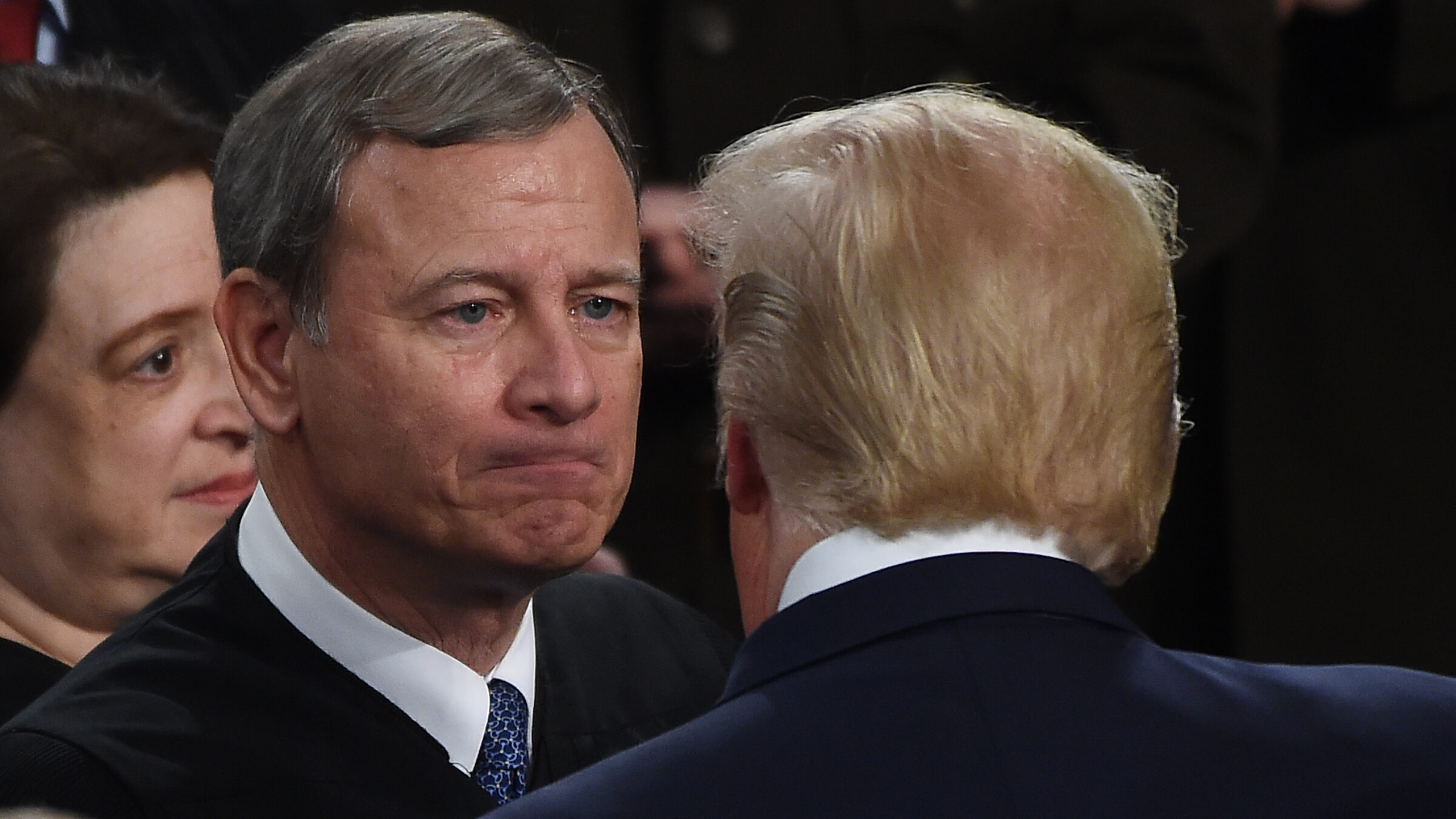

When the justices you appointed did what you asked (Photo by JEFF KOWALSKY/AFP via Getty Images)

Trump v. United States—which, to be clear, is the name of a Supreme Court case, not a short summary of the state of American politics—is not technically the end of Special Prosecutor Jack Smith’s prosecution of Trump in Washington, D.C. But every aspect of the Court’s handling of this case, from the glacial pace of its resolution to the substantive result that goes beyond even what Trump asked for, was designed to rescue Trump from facing a jury of his peers before polls open in November. For the six Republican justices in the majority, the practical consequences for the presumptive Republican presidential nominee are what matter: Voters will select the next chief executive of the federal government without a legal determination about whether one of their two options recently tried to overthrow it.

Legal pundits have long cast Roberts as the Court’s resident institutionalist, a conservative justice who would nonetheless refuse on principle to endorse Trump’s myriad efforts to undermine the hallowed rule of law. This narrative has always been wrong, but never more so than today: To the extent that John Roberts ever imagined himself as a meaningful check on Trump’s power, that version of John Roberts is gone. He is as staunch a proponent of the MAGA agenda as any of his colleagues who fly coup-sympathetic flags above their homes; he just manages to be a little less uncouth about it.

Roberts’s opinion divides the scope of presidential immunity into three basic categories. First, he addresses acts that are within a president’s “conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority”—that is, duties spelled out in Article II of the Constitution. In these situations, Roberts writes, a president’s immunity is absolute; however they choose to wield their power, “Congress cannot act on, and courts cannot examine” it.

This reads as almost tautological: an affirmation that the president is allowed to do what the president is allowed to do. But as Sotomayor points out in dissent, Article II uses vague language that could, according to the majority, immunize cartoonishly unlawful actions from prosecution. For example, Article II gives the president the exclusive authority to command the armed forces; under Roberts’s formulation, it is not clear what (if anything) would prevent a president from invoking this authority to order SEAL Team 6 to assassinate a political rival. In retrospect, Trump’s error on January 6 might have been charging mere civilians with the task of overthrowing the government; had he instead commissioned the military to march to the Capitol and murder Mike Pence, he’d be in an (even) stronger legal position than he is right now.

Perhaps the wildest aspect of Robert’s analysis is his inclusion of the president’s general duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” in his list of a president’s “conclusive and preclusive powers.” This, in theory, could encompass just about any decision a president makes inside the confines of the Oval Office. As Sotomayor writes, the doctrine functions as a “loaded weapon” in the hands of any president who would “place his own interests, his own political survival, or his own financial gain above the interests of the Nation.”

Roberts’s opinion deals mostly in abstractions, since he really, really doesn’t want to talk about January 6. But just based on this, it’s hard for me to see how a president could be prosecuted for ordering SEAL Team 6 to assassinate a political rival https://t.co/vK54niPiEN pic.twitter.com/Kebc43qhik

— Jay Willis (@jaywillis) July 1, 2024

Incredibly, the opinion gets more unhinged from here. For “official acts” that fall outside the scope of Article II, Roberts writes, presidents enjoy “at least presumptive immunity,” which prosecutors can overcome only if they prove that prosecution would pose no “dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” When differentiating between “official” and “unofficial” acts, Roberts continues, courts may not inquire into a president’s “motives,” which, he says, risks weaponizing the legal system for an “improper purpose.”

Roberts’s putative concern is with specious investigations that allow bad-faith prosecutors to second-guess every decision a president makes. But together, the absoluteness of Roberts’s standard and the weight of the burden of proof render this “test” a dumb joke. “Under that rule, any official use of official power for any purpose, even the most corrupt purpose indicated by objective evidence of the most corrupt motives and intent, remains official and immune,” Sotomayor writes. “It is hard to imagine a criminal prosecution for a President’s official acts that would pose no dangers of intrusions…in the majority’s eyes.”

As you might expect, after tailoring a legal framework to protect Donald Trump, Roberts’s application of this framework to the case at hand is very favorable to Donald Trump. For example, Roberts concludes that Trump enjoys absolute immunity for asking the Department of Justice to prosecute fake voter fraud cases, since this implicated the “investigative and prosecutorial decisionmaking” authority that is the “special province of the Executive Branch.” That these demands were baseless components of a slow-motion coup attempt has no bearing on Roberts’s analysis, which transforms the old Richard Nixon adage—“it’s not illegal when the president does it”—into an ironclad principle of constitutional law.

The majority returns most of the charges in the indictment to the trial court for further fact-finding, which means that parts of Smith’s prosecution may eventually go forward. But the calendar matters: With five months to go until the election, there simply isn’t time to hold a trial before then, even if the lower courts were to resolve these questions tomorrow. This is perhaps the most important aspect of how the majority handled the case: It threw out some charges against Trump, and empowered him to run out the clock on the rest.

(Photo by Olivier DOULIERY / AFP)

Roberts’s language throughout the opinion is pretty staid, and by assigning it to himself, he ducked the unflattering headlines that would have followed a deranged majority opinion written by, say, Clarence Thomas. But this is a matter of form, not substance. The result in Trump v. United States is still a full-throated endorsement of the absolute power Trump craves, rendered in anodyne legalese and sprinkled with mealy-mouthed appeals to the importance of our great nation’s tripartite system of governance. It creates a brand-new version of the presidency in which a re-elected President Trump could spend four years doing—and here I apologize for the legal jargon—whatever the fuck he wants. In dissent, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson calls the opinion a “five-alarm fire that threatens to consume democratic self-governance,” a characterization that could just as easily apply to the Court that issued it.

The conservative justices frame their task as difficult and complicated in light of the long-term consequences: They cannot afford to “fixate…on present exigencies,” Roberts explains, in ways that might make future presidents “unduly cautious in the discharge of [their] official duties.” But it is striking how much this lazy concern-trolling ignores what Donald Trump actually did here, in the real world, right across the street from where the justices go to the office every day. Whatever Trump was doing while trying to foment a mass death event at the Capitol, he was not “discharging his official duties.” As it so often does, the Court deals in abstractions to gloss over the practical consequences of its decision: By endlessly wringing its hands about the implications for hypothetical presidents who are not aspiring dictators, the Court hands a triumphant victory to a real-life president who is one.