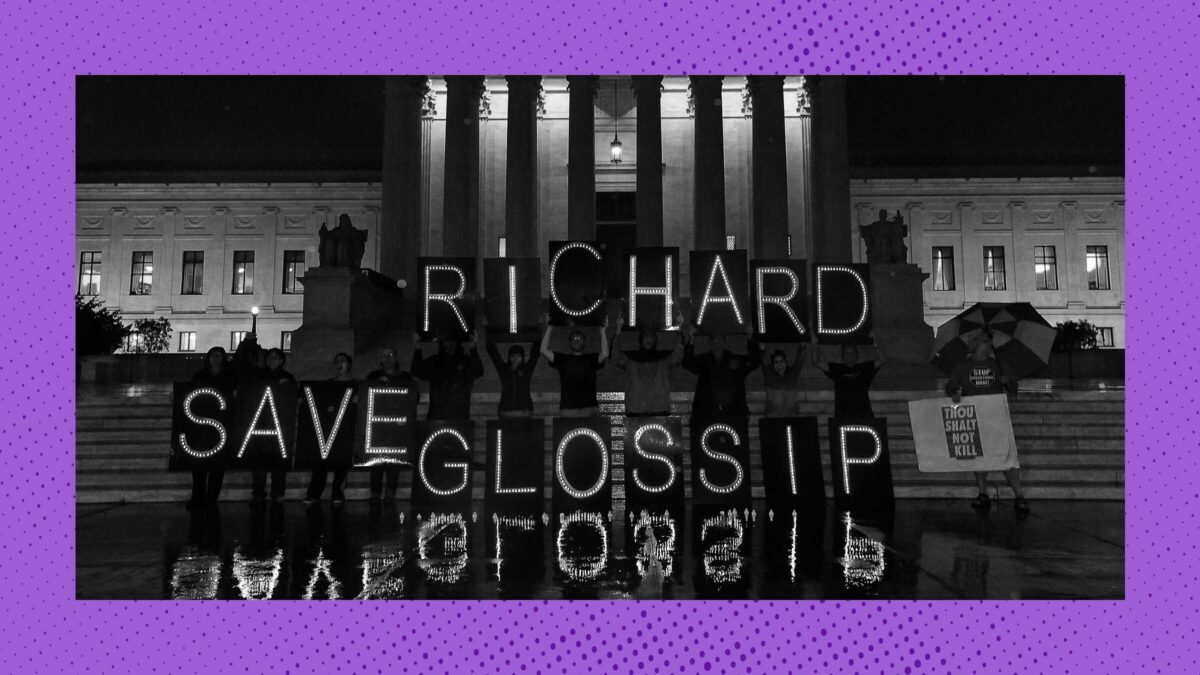

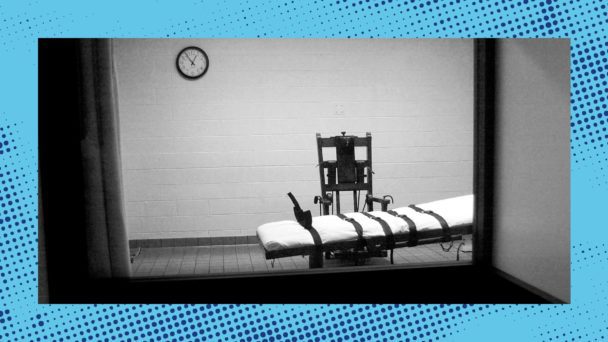

Richard Glossip has been served a last meal three times, coming perilously close to execution for a crime he almost certainly did not commit. And one-third of the justices on the Supreme Court are tired of all the hold up.

On Wednesday, the Court heard oral argument in Glossip v. Oklahoma, an unusual case in which both Richard, the person on death row, and Oklahoma, the state that put him there, are asking the justices for permission to let him live. Two decades ago, Glossip was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese based on the testimony of Justin Sneed, the man who actually killed Van Treese by beating him with a baseball bat. In an admitted effort to save himself from the death penalty, Sneed testified that he murdered Van Treese, who owned the motel where both men worked, because Glossip offered him $10,000 to do so. The gambit was successful: Glossip, not Sneed, was sentenced to die.

In recent years, multiple independent investigations commissioned by Oklahoma officials unearthed a truckload of errors in Glossip’s trials, including the suppression of key evidence that Sneed lied under oath about his psychiatric state at the time of the murder. When he killed Van Treese, Sneed was dealing with undiagnosed bipolar disorder, which, when combined with his methamphetamine usage, could have contributed to impulsive and violent behavior. After his arrest, a psychiatrist prescribed him lithium to treat his bipolar disorder. But under oath, Sneed said he’d only asked for Sudafed because he had a cold, and that he’d somehow been accidentally given the lithium, thus lying about his mental state and denying Glossip the opportunity to challenge Sneed’s testimony.

Because of the cumulative errors in the case, the state’s chief law enforcement officer, Attorney General Gentner Drummond, has since admitted that he has “lost faith in the basic fairness of the prosecution.” Last year, Drummond requested that the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals vacate Glossip’s conviction and death sentence and remand his case for a new trial.

Astonishingly, the state court refused to do so, which is how Glossip’s case ended up before the U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday. Attorneys general do not confess errors lightly. And Paul Clement, a prominent Supreme Court lawyer who represented Oklahoma before the justices, bluntly explained why the state would take this rare step, fighting side by side with a man it had planned to execute. “Our prosecutors elicited perjury here, and a man’s going to go to his death,” Clement said. “We can’t allow that to happen.”

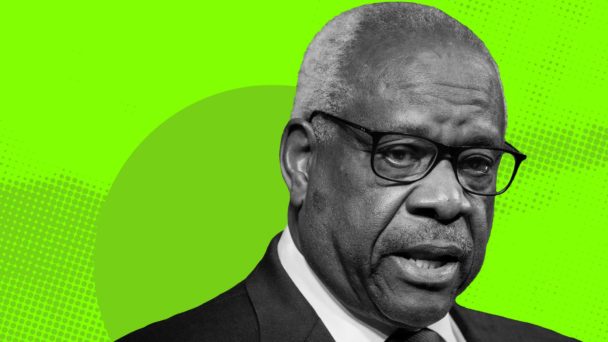

At oral argument, the Democratic justices were understandably bothered by the idea of the state executing someone after an unfair, unreliable, unconstitutional trial. Yet Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, along with Chief Justice John Roberts, distinguished themselves from their colleagues in the extent to which they did not give a damn. While a death row prisoner and a would-be executioner were united in trying to save a man’s life, one-third of the Supreme Court impatiently searched for reasons to kill him.

Roberts pondered whether perjury is that big a deal anyway, pointing out that the jury was already aware that Sneed was taking lithium, and suggesting that it was immaterial that it was prescribed by a psychiatrist, rather than in some kind of Sudafed mix-up. “Do you really think it would make that much of a difference to the jury?” Roberts asked. Justice Sonia Sotomayor intervened to make clear that that was only part of the problem: “The issue wasn’t about him taking lithium,” she said. “The issue was about why he was taking the lithium.” Again, Glossip did not have the opportunity to develop any related defenses, or to challenge Sneed’s credibility for lying under oath—or, for that matter, the credibility of the prosecutor who was aware that Sneed was lying.

Later, when Roberts again floated the argument that the perjury was immaterial in this case, Justice Elena Kagan shut it down. “That seems pretty material to me,” she said. “Your one witness has been exposed as a liar.”

Thomas, meanwhile, took offense to the accusation that the prosecutors in Glossip’s case were anything less than honest, going on at length about their lack of any opportunity to defend themselves. “Did you at any point get a statement from either one of the prosecutors? Did you interview them?” Thomas asked Glossip’s lawyer, as if that were his job. “Not only are their reputations being impugned, but they are central to this case,” he continued. “It would seem that an interview of these two prosecutors would be central.” To Thomas, a prosecutor’s reputation is worth a great deal, while a man’s life is worth very little.

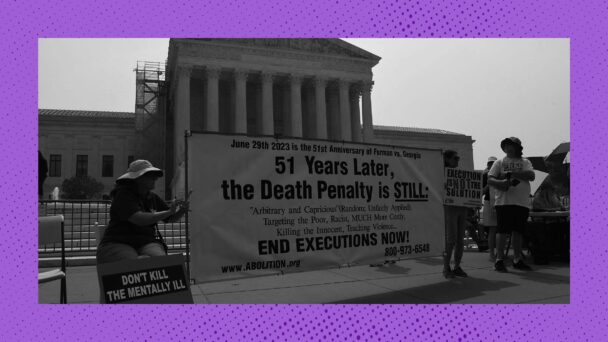

Alito also made no secret of his disinterest in Glossip’s life, but took a different tack, ignoring the substance of Glossip’s case and pushing to resolve the case on procedural grounds. Oklahoma law includes a procedural bar intended to prevent repeated appeals by people who have been convicted of crimes: Courts don’t consider post-conviction relief claims unless those claims couldn’t have been raised earlier, or unless there is clear and convincing evidence that the convicted person is actually innocent.

The Oklahoma attorney general waived the bar in Glossip’s case, but on Wednesday, Alito was eager to reinstate it. “Whether the waiver of a procedural bar must be accepted by the Oklahoma court is a question of Oklahoma law, right?” he asked. “The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals can say: We always accept these, we never accept them, or sometimes we accept them, right?” In other words, whether Oklahoma gets to execute someone who didn’t get a fair trial is the Oklahoma court’s prerogative, not the Supreme Court’s. (Given the lengths to which the Court will go in other contexts to butt its way into things it should stay out of, Alito picked a hell of a time to say that this was not the Court’s business.)

These lines of questioning about local procedure, besmirched prosecutors, and purportedly consequence-free perjury were distractions from the real issue before the Court in this case: the possible state-sanctioned killing of an innocent man. Yet Alito, Thomas, and Roberts were inventing any reason they could to make a state execute someone whose conviction is so riddled with errors that the state stopped defending it. The bloodlust displayed by one-third of the Court is a damning indictment of the whole institution.