On November 17, 2022, Kenneth Smith spent four agonizing hours strapped to a gurney waiting for the state of Alabama to kill him. Smith, who was convicted of murder in 1988 and sentenced to die by lethal injection, could do nothing but watch as correctional officers poked and prodded his arms and hands, searching fruitlessly for veins. Then, without warning or explanation, the officers—it’s not clear if any of them were medical professionals—tried a different approach, jabbing a large needle underneath Smith’s collarbone, which made him cry out in pain and plead for his lawyers or the court to intervene.

Smith’s death warrant expired at midnight, and because officials couldn’t find his veins in time, they had to stop the execution attempt. When they unstrapped Smith from the gurney, he was hyperventilating and couldn’t sit, stand, or walk without help. It was Alabama’s third failed execution attempt in six months. Smith, who remains on death row, now experiences back spasms and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

In 2019, the Court wrote in Bucklew v. Precythe that the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment,” does not “guarantee a prisoner a painless death.” But the Bucklew Court did hold that people on death row can challenge a state’s execution method if they can show that procedure would cause them “superadded” pain—and if they can point to a “feasible and readily implemented” alternative method that would “significantly reduce” the risk.

So, after Alabama’s disastrous attempt to execute him, Smith asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit to stop the state from trying to kill him via lethal injection. Instead, he asked that Alabama use nitrogen hypoxia, a method of asphyxiation in which people breathe pure nitrogen until they die. The state legislature approved the use of nitrogen hypoxia in 2018; Oklahoma’s and Mississippi’s legislatures have done so, too. In Alabama, at least 48 people on death row have opted for this method of execution, though no state has yet attempted it.

The Eleventh Circuit granted Smith’s request, finding that he had shown that the state would have “extreme difficulty” accessing his veins, due in part to Smith’s age, weight, and the immense anxiety that the execution provokes. The state appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that because it has yet to finalize an execution protocol for nitrogen hypoxia, the Court should allow it to force Smith to relive last fall’s nightmare.

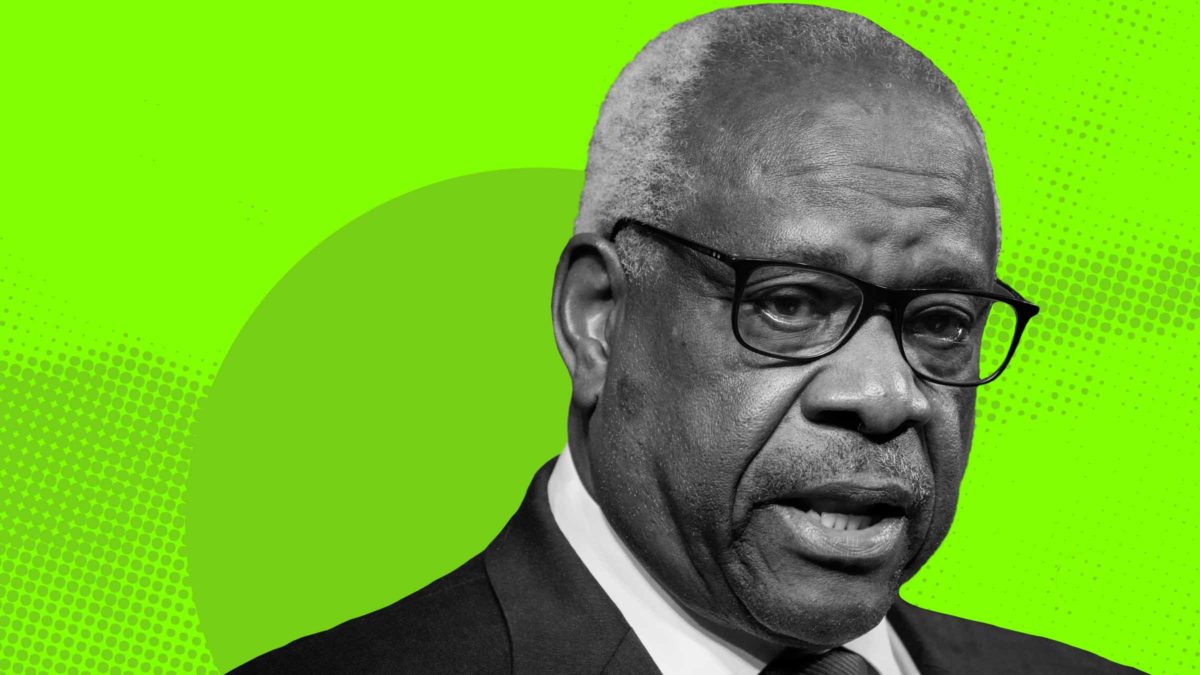

On Tuesday, the Court refused to do so. But Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Samuel Alito, dissented. If it were up to the two of them, the government would be free to subject people to severe pain without once worrying about running afoul of the Constitution’s protections for people sentenced to death.

Thomas’s argument is that because Alabama has not finalized its nitrogen hypoxia protocol, let alone killed anyone using it, Smith didn’t prove that an alternative execution method is “available.” Of course, it’s Alabama’s job to craft an execution protocol, not Smith’s. Thomas’s argument here would allow the state’s five-years-and-counting delay to justify its failure to give Smith a choice to which he is legally entitled. His opinion characterized the legal availability of nitrogen hypoxia as a “threadbare allegation” and “simply irrelevant, without more.”

Another theme of Thomas’s dissent was his oft-repeated complaints that portray people on death row as dishonest abusers of the court system who use legal technicalities and procedural tricks to delay their executions. The Court’s refusal to grant Alabama’s request, he argued, will become yet another “instrument of dilatory litigation tactics” in death penalty cases. For Thomas, constitutional rights are not for everyone, but only for those whom he believes to be worthy of their protections.

The Supreme Court’s death penalty jurisprudence is horrific and monstrous, but it has, at the very least, granted people on death row the option of choosing a less painful method of execution. Yet Alito and Thomas don’t want people to actually exercise that right. If there’s one thing they love more than the state executing people, it’s the state executing people as quickly and cruelly as possible.