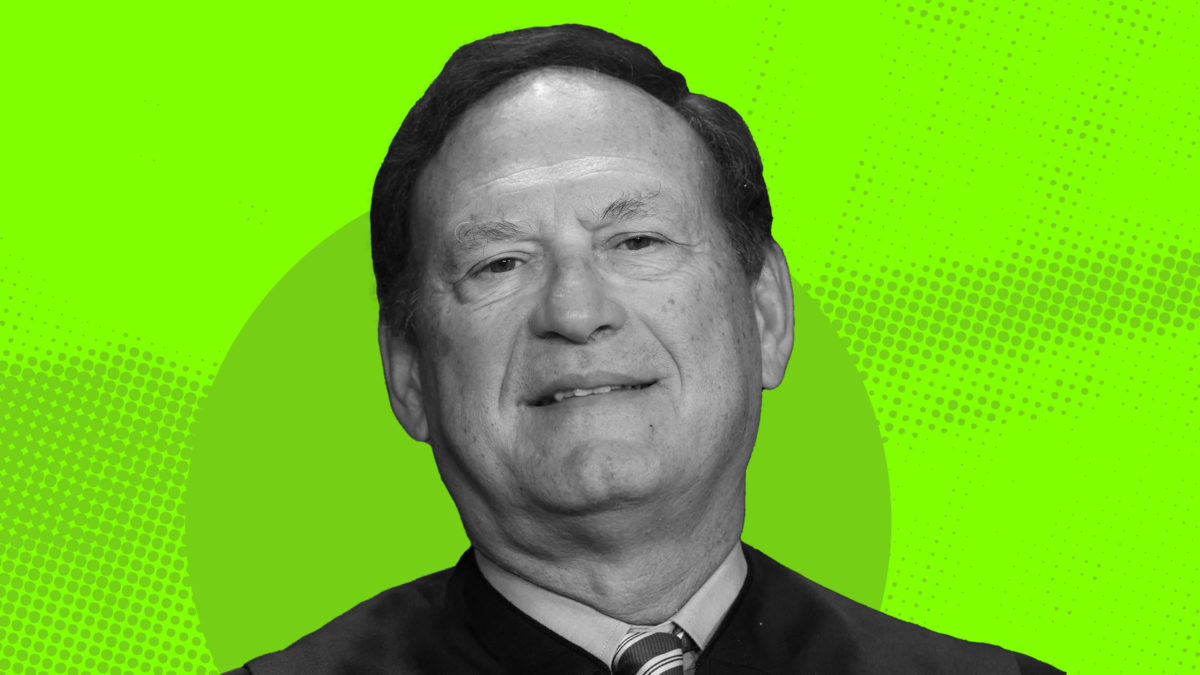

In May 2024, the New York Times revealed that Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito had flags affiliated with far-right extremist movements flying outside of his residences. Alito’s conduct triggered widespread demands for higher judicial ethics standards and meaningful enforcement when those standards are breached. And last week, the legal system actually meted out some discipline in relation to the incident…but not to Alito. Chief Judge Albert Diaz of the Fourth Circuit issued an order on December 10 finding that a federal judge violated ethical rules by publicly acknowledging Alito’s clear lapses in ethical judgment.

The Wall Street Journal reported on Tuesday that the target of the disciplinary measures was Michael Ponsor, a Senior Judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts. Ponsor published an essay in the New York Times over the summer titled “A Federal Judge Wonders: How Could Alito Have Been So Foolish?” This was a very good question. The foolishness at issue was an upside-down American flag—a symbol adopted by proponents of overthrowing the 2020 election on the false grounds that it was “stolen” from Donald Trump—which neighbors spotted in front of Alito’s Virginia home in the days following the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol. Two years later, people saw an “Appeal to Heaven” flag—an obscure emblem of Christian theocrats—hoisted high at Alito’s New Jersey vacation home. (Yes, two different flags, and two different houses.)

When a Supreme Court justice is exposed as a conspiracy-addled, antidemocratic reactionary, it becomes a bit more difficult for the Court to maintain its reputation as an impartial administrator of equal justice for all. Yet, somehow, Alito has faced no consequences for his misconduct, while Ponsor’s discussion of that misconduct gave rise to an ethical inquiry conducted by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. The court’s determination that Ponsor violated ethics rules by publishing criticism of Alito shows that the judiciary is much less concerned with meeting ethical standards than it is with maintaining a myth that the standards are met.

Ponsor bluntly observed in his essay that “any judge with reasonable ethical instincts would have realized immediately that flying the flag then and in that way was improper. And dumb.” The essay also acknowledged that Alito’s flags are “viewed by a great many people as a banner of allegiance on partisan issues that are or could be before the court,” meaning their display would be corrosive to the public trust that courts depend on. Finally, Ponsor recognized that the flimsy Code of Conduct announced by the Court last year is an insufficient substitute for one’s own moral compass. “Basic ethical behavior should not rely on laws or regulations,” he wrote. “It should be folded into a judge’s DNA. That didn’t happen here,” Ponsor concluded.

Within days of the essay’s publication, a rightwing advocacy group filed a complaint under the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act. (The founder of the group is a former clerk for Justice Neil Gorsuch who also notably advocates for incarcerating “the violent Black underclass.”) The complaint characterized Ponsor’s essay as a “highly inappropriate, baseless, and prejudicial political speech by a judge against another judge while he is deciding the legal fates of criminal defendants going through the judicial process.” Chief Judge Diaz, an Obama appointee, reviewed the complaint and published the order finding that Ponsor violated the Code of Conduct for United States Judges.

The central component of Ponsor’s misconduct appears to be discussing the misconduct of someone with more power than him. Diaz wrote that Ponsor “criticized the ethics of a sitting Supreme Court justice” and “such comments diminish the public confidence in the integrity and independence of the federal judiciary,” in violation of the Code. The order does not discuss whether that judicial integrity actually exists, or whether the public’s confidence is warranted. Perversely, the ethics enforcement punishes Ponsor for articulating higher ethical expectations for his profession.

Diaz also found that the essay’s “political implications and undertones” violated the Code’s prohibition on public comments about the merits of pending cases. Ponsor did not reference any pending case in his essay. But given the timing, Diaz said “it would be reasonable for a member of the public to perceive the essay as a commentary on partisan issues and as a call for Justice Alito’s recusal” in the then-pending January 6 cases. Whether the public reasonably perceived Alito’s flags as partisan commentary, and whether Alito should in fact have recused, were again besides the point under Diaz’s analysis.

Along with his own memorandum and order, Diaz released an apology letter written by Ponsor. In the letter, Ponsor expressed contrition for potentially undermining the public’s confidence in the integrity of the judicial system by criticizing Alito’s ethical judgment. Ponsor also said he especially regretted that the essay could have been interpreted as a call for Alito’s recusal. “The fact that I did not have any particular case in mind when I drafted the piece does not reduce the gravity of my lapse,” he wrote. Diaz found that the apology letter constituted “appropriate voluntary corrective action,” and closed the complaint proceeding accordingly.

As a lower court judge who must apply the Court’s decisions—and as a person who lives under them, for that matter—Ponsor has a vested interest in both the appearance and the actual existence of the Court’s integrity. But pushing for that integrity, rather than playing along with the legal system’s charade of propriety, is apparently a disciplinary offense. The determination that criticizing the Supreme Court is literally against the rules is frustrating confirmation that the Court’s justices need not fear any accountability for their bad actions.

Representative Jamie Raskin observed yesterday that “the Roberts Court’s ‘rules for thee and not for me’ approach to judicial ethics” allows its far-right justices “to ignore the ethics rules that bind every other judge.” Alito’s open expressions of sympathy to insurrection and Christian nationalism should undoubtedly call into question his compliance with what little ethical standards the Supreme Court claims to have. By treating the mere mention of Alito’s ethical problems as an ethical problem in and of itself, the court’s ruling deliberately deters judges from speaking up about the Supreme Court’s misconduct. In so doing, the judiciary’s ethics enforcement props up a failing institution, and ensures that real ethical issues go unresolved.