Earlier this summer, Justice Samuel Alito sat for two fawning profiles published in The Wall Street Journal. (The headline on one: “Samuel Alito, the Supreme Court’s Plain-Spoken Defender.”) The interviews were jointly conducted by the WSJ’s James Taranto and David Rivkin, a conservative lawyer and occasional legal commentator. Rivkin currently represents the Federalist Society’s Leonard Leo in a congressional investigation into Leo’s role as the Republican justices’ luxury travel agent. And as fate would have it, Rivkin is representing the petitioners in Moore v. United States, a case the Court will hear this term that could place sharp limits on the government’s ability to tax the uber-rich.

In response, last month, Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Dick Durbin sent a letter to Chief Justice John Roberts calling for Alito’s recusal in Moore, given Rivkin’s co-authorship of, again, an interview headlined “Samuel Alito, the Supreme Court’s Plain-Spoken Defender.” Among Durbin’s concerns was that Rivkin’s “efforts to help Justice Alito air his personal grievances could cast doubt on Justice Alito’s ability to fairly discharge his duties in a case in which Mr. Rivkin represents one of the parties.”

It might strike you, a normal person, as inappropriate for Alito to participate in Moore; you might think Alito’s failure to recuse would create, at minimum, the appearance of corruption. But, according to Alito, that would make you just a simple rube who doesn’t understand how good he is at his job. Today, Alito released a statement declaring that “no valid reason” exists for him to recuse in Moore, and that there was “nothing out of the ordinary about the interviews in question.” Rivkin, Alito explains, writes “as a journalist, not an advocate.”

The notion that Alito’s vote in Moore might be affected by his relationship with Rivkin, Alito says, “fundamentally misunderstands the circumstances under which Supreme Court Justices must work.”

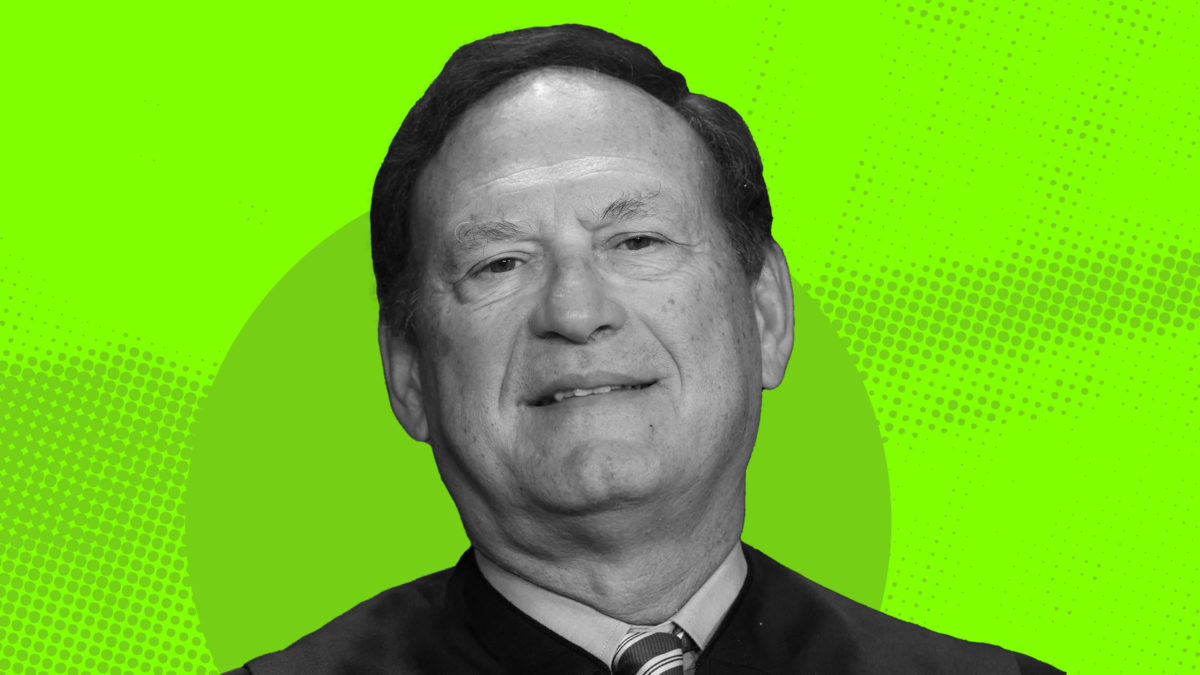

When you were secretly hoping for something cooler than “Plain-Spoken Defender” (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Alito’s statement seems to herald a curious new standard that would broaden the kinds of relationships justices could engage in with attorneys who appear before them. Imagine: I had dinner at their house last night as a friend, not as a life-tenured Supreme Court justice deciding their client’s fate today! I’m joking, but this isn’t that far-fetched: Elite legal circles are already small and incestuous, and Alito points out that the Court would constantly be short-staffed if the justices had to recuse every time a friend, former colleague, or former clerk (or former soft-focus Wall Street Journal profile writer) argues a case before them.

This was not, in Alito’s mind, a persuasive argument for formalizing recusal rules, and perhaps for adding more justices to the Court to ensure that a meaningful code of ethics does not prevent it from functioning. Rather, it was an argument to just trust him to forget that friendships exist the moment he clocks in for work. “We are required to put favorable or unfavorable comments and any personal connections with an attorney out of our minds and judge the cases based solely on the law and the facts,” he concludes. “And that is what we do.”

Alito is trying to tap into the myth that the Supreme Court is the embodiment of justice itself, and that Supreme Court justices are beyond reproach by virtue of the fact that they are Supreme Court justices. Concerned observers simply don’t understand his work; common folk may be influenced by personal relationships, but Alito, because he wears black pajamas to work, doesn’t consider such lowly things. The public is supposed to believe that the Court’s decisions—decisions that consistently enrich and empower his friends and hurt his enemies—are solely the product of the objective applications of law to facts, nothing more. It is an unimpressive attempt to disguise the abundance of causes for concern about the way this Court wields its power: however it wants.