Early Tuesday morning, the Department of Justice released Special Counsel Jack Smith’s final report of his efforts to prosecute former and soon-to-be President Donald Trump for trying to overturn the results of the 2020 election. After Trump’s win in the 2024 election, Smith asked the presiding judge to dismiss the case and then abruptly resigned, citing a longstanding Department of Justice policy against prosecuting sitting presidents. Both requests were formalities, given Trump’s public promise to fire Smith within “two seconds” of taking office.

But in his report, Smith says that if the 2024 election had come out differently, he would still be doing his job right now. He expresses confidence that he had Trump dead to rights, and that the case, which he says he “stands fully behind,” would not have been especially close. “But for Mr. Trump’s election and imminent return to the presidency, the office assessed that the admissible evidence was sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction at trial,” Smith wrote.

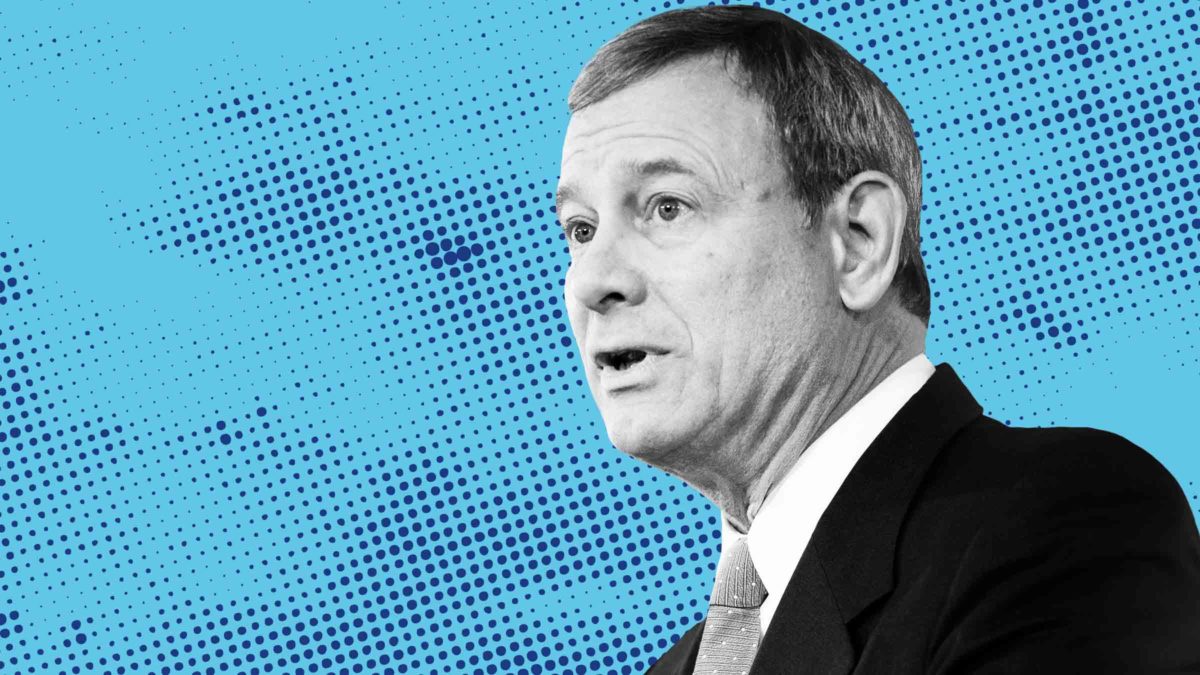

On the one hand, “I had him, I swear” is what any prosecutor would say about a case that, for reasons beyond their control, they could not see all the way through. But on the other, Smith spends as much time recapping the factual background as he does detailing the multitude of roadblocks erected by the federal judiciary that made his job harder: principally, Chief Justice John Roberts and the other members of the Supreme Court’s six-justice conservative supermajority, who as the election drew nearer did everything in their power to help Trump, the presumptive nominee of their preferred political party, to run out the clock on the legal process.

Over the past few months, Trump, his allies, and a select few of the legal profession’s more credulous dorks have framed the result in 2024 as a de facto exoneration for Trump. The only reason the election could function as a get-out-of-jail free card in the first place is the willingness of sympathetic federal judges to kick the can down the road on his behalf. Roberts, a lifelong Republican, wants other Republicans in elected office, and had no problem reshaping the law to keep Donald Trump safely beyond the criminal legal system’s reach.

The facts in Smith’s report are mostly matters of public record, and will be familiar to anyone who remembers watching several thousand Trump supporters attack the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. The more interesting sections of the report discuss the behind-the-scenes impact of the Court’s July 2024 decision in Trump v. United States, in which Roberts invented a sweeping immunity doctrine for “official acts” of presidents accused of crimes, on Smith’s efforts to hold Trump accountable for insurrection-adjacent conduct. (Smith does not spend his time arguing with the majority in that case, but in a footnote, he quotes Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s characterization of Trump as creating a “law-free zone around the President,” which is about as close as a federal prosecutor gets to saying that the Supreme Court is full of shit.)

The result in Trump, Smith wrote, did not change his bottom-line conclusion that he could prosecute the former president. But it did throw the brakes on the proceedings, forcing Smith’s team to undertake an “exhaustive and detailed review” of the facts and evidence in order to determine how they could proceed. The report also details several legal questions left unresolved by Trump that, Smith says, the Court “would likely have had to address before the prosecution could have proceeded to trial”—for example, the precise scope of “core” exercises of presidential power that are immune from prosecution, and the limits of the “presumptive” immunity that Roberts created for “non-core” acts, too.

In August, Smith obtained a superseding indictment designed to be consistent with the opinion in Trump. But at that point, a full year had passed since the original indictment, and as of Election Day, the prosecution and defense were still fighting over whether material mentioned in the superseding indictment, too, might be subject to Trump immunity. In light of the election results and Smith’s subsequent decisions to dismiss the case and resign his office, it is safe to say that no court, Supreme or otherwise, will be ruling on those issues anytime soon.

Part of the reason Smith ran out of time is that the Biden administration did not give him enough of it. Under the leadership of Attorney General Merrick Garland, the Department of Justice did not take meaningful steps to prosecute Trump for his role in January 6 for some two years, hoping instead that a combination of public outrage, the work of the House Select Committee on January 6, and the simple passage of time would render Trump politically irrelevant. As Smith notes, Garland did not even appoint Smith until November 2022, and only because Trump’s decision to seek re-election compelled Garland to tap an independent prosecutor to direct the Department of Justice’s investigation going forward.

As it turns out, this reluctance to do the basic work of defending democracy from people who attacked it had consequences: While Smith was trying to speed-run a prosecution that should have started during Biden’s first week in office, the Republican Party unified around the message that any effort to prosecute their man for his crimes was (yet another) partisan witch hunt. Smith’s report contains probably the strongest language a Department of Justice official has used or will ever use to publicly describe the events of January 6. It is a fitting tribute to Garland’s legacy that you only got to read it two months after Trump won another presidential election, once again wriggling free of the criminal legal system’s purportedly firm grasp.

But if Garland is responsible for the prosecution getting off to a late start, it is the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority who ensured that it will remain incomplete. By using the powers of their offices to drag things out, the Republican justices gave Trump the time he needed to defend himself in the court of public opinion, persuading a dispositive number of voters that his nationally televised efforts to steal an election were not such a big deal after all. The result might not be the formal exoneration for which Trump hoped. But what Roberts and company understood all along is that a week from now, no one will remember the difference.