On Tuesday, the Supreme Court issued a one-page order in United States v. Shilling, an ongoing legal challenge to President Donald Trump’s efforts to ban transgender people from serving in the U.S. military. The procedural background is complicated, but the upshot of the Court’s order is not: Even as Shilling continues to work its way through the courts, the administration may begin firing transgender troops at its earliest convenience. For the six conservative justices in the majority, there is no crisis quite as urgent as a federal judge trying to prevent a Republican president from doing whatever he wants, whenever he feels like it.

This case started back on January 27, when Trump issued an executive order declaring “adoption of a gender identity inconsistent with an individual’s sex” to be inconsistent “with a soldier’s commitment to an honorable, truthful and disciplined lifestyle.” A month later, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth announced that the Department of Defense would implement the order by mandating honorable discharges for all transgender servicemembers, whose eligibility for severance pay would hinge on whether they agreed to characterize their separations as “voluntary.” The policy also barred the government from covering costs for gender-affirming healthcare, and (of course) instituted a new pronouns policy requiring the use of formal military salutations— “Yes, sir” and “Yes ma’am”—that “reflect an individual’s sex.”

On March 4, a coalition of transgender servicemembers—headlined by Emily Shilling, a 19-year Navy veteran—sued in federal district court in Washington state, arguing that the ban violated their rights under the First and Fifth Amendments. As part of the lawsuit, they asked the court for a preliminary injunction that would temporarily bar the White House from enforcing the ban for as long as the case is pending. This is a common request in challenges like this one, and addresses both the plodding pace of litigation and the practical implications of allowing a possibly unconstitutional law to take effect immediately: If you get fired because of a policy change, and a court later declares the policy unlawful and orders your reinstatement with back pay, great, but that won’t cover the rent payments you already missed.

The judge, George W. Bush appointee Benjamin Settle, granted Shilling’s request for a preliminary injunction, characterizing it as “not an especially close question.” Any burden on the government associated with a brief delay in enforcement “pales in comparison to the hardships imposed on transgender service members,” he wrote. “There can be few matters of greater public interest in this country than protecting the constitutional rights of its citizens.”

The Court’s order on Tuesday, from which all three liberal justices dissented, effectively overrules Settle’s decision. This means that while federal judges continue to grapple for God knows how long with outstanding legal questions about the ban’s constitutionality, the administration is free to implement the ban as if there were no remaining questions about it. This outcome doesn’t technically resolve the merits of Shilling in the administration’s favor. But it does give Trump and Hegseth the green light to purge the ranks of trans people, which is all they really cared about doing in the first place.

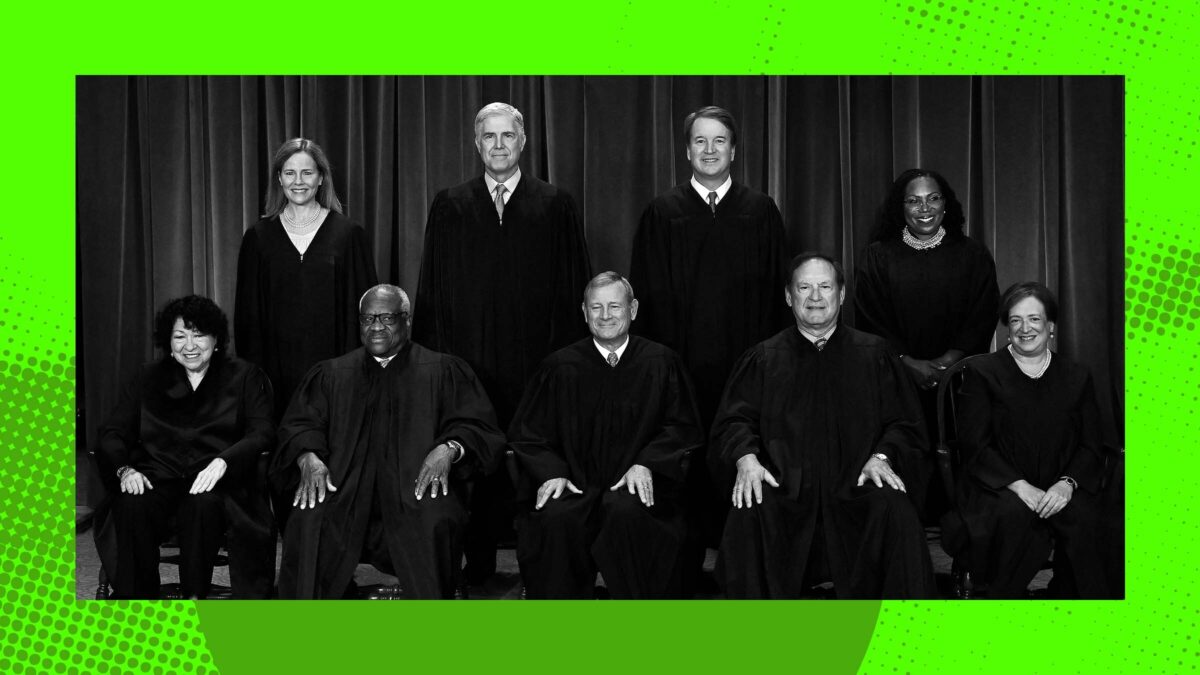

(Photo by Andrew Harnik/Getty Images)

When evaluating both requests for preliminary injunctions and requests to stay these injunctions, judges are supposed to consider the extent to which each side—the party requesting an injunction and the party opposing it—will suffer “irreparable” harm if they lose. Irreparable harm just means any harm for which courts cannot order a legal remedy, like money damages, once the case is fully resolved. If an environmental group sues to protect a forest of 2,000-year-old sequoias from getting clearcut by an international timber conglomerate, for example, they will probably ask the court for a preliminary injunction to block any logging in the meantime. This accounts for the simple fact that if the company razes the forest but then loses the case, “reconstitute the giant pile of wood chips into living trees and put each one back exactly where you found it” is not a viable solution to the problem.

The conservative justices’ decision to side with Trump here reveals a lot about whose interests are sufficiently important to merit intervention, whose interests they do not consider worthy of their time or attention. In their brief, Shilling and company argue that although their constitutional rights are of course important, the real-world stakes might be even higher: Allowing the ban to take effect would result in them losing their jobs, their healthcare, and their careers overnight. An amicus brief points out that although servicemembers can appeal administrative separations if they so choose, this particular discharge method is a “harsh process normally reserved for serious misconduct and failure to meet performance standards.” Hegseth’s choice to use it to implement the ban, they continue, would permanently stigmatize servicemembers based on their trans status—an “unprecedented and un-American” result.

In his order entering a preliminary injunction, Settle agreed. Permanent disqualification from military service is not a “temporary loss of income,” he wrote, but a “definitive loss of career in service to their country” that would be “directly attributable to the likely unconstitutional [ban].” Even if servicemembers were to appeal their separations, it’s not clear how receptive the powers that be would be to such claims, or if, practically speaking, anyone who wins their appeal could thereafter return to their old jobs as if nothing had ever happened. Given that transgender people have been serving in the military for decades without single-handedly triggering its collapse, the notion that Pete Hegseth must be allowed to start firing them posthaste in the name of national security is not especially persuasive.

The White House understands all this, and so it takes a more abstract approach to “irreparable harm” in its briefing, framing the danger as not to actual people or their fundamental rights, but to the conservative legal movement’s ever-expanding conception of the scope of executive power. When “an unelected judge usurps the role of the political branches in operating the Nation’s armed forces,” writes Solicitor General D. John Sauer, they “injure our democratic system” by “preventing the executive branch from carrying out its work.” In other words, because the Constitution designates the president as commander-in-chief, even a temporary constraint on his exercise of that power inflicts a wound from which the republic cannot recover.

Usually, comparing the conclusions drawn by federal judges applying the dueling multi-pronged tests for granting versus staying preliminary injunctions is fodder for the least interesting lecture in a law school civil procedure course. But for anyone who is not a tenured law professor or a sleep-deprived first-year law student, the policies the Court greenlights using its power are far more important than the words it uses to do so. Trump’s official position in this case is that being forced to wait a bit longer to implement gutter transphobia as defense policy would constitute an untenable legal emergency that the Constitution cannot tolerate. The Court, by a 6-to-3 vote, decided he is right.

Many things the Roberts Court does, especially in cases on its emergency docket, look a lot like Shilling: Terse, unreasoned orders, inscrutable to anyone who isn’t familiar with the case, the briefs, and the procedural posture at that particular moment. The conservative justices have learned to use this dynamic to their advantage, handing down sweeping rewrites of the law in formats that obfuscate the substantive monstrousness. This time, they declared the rights and lives and livelihoods of thousands of transgender servicemembers to be less important than Trump’s unfettered authority to implement his policy agenda. In the justices’ view, his priorities deserve their indulgence. His victims deserve only their scorn.