On Monday, in an unsigned, one-paragraph order, the Supreme Court’s six conservatives allowed President Donald Trump to functionally dismantle the Department of Education. The Court’s shadow docket decision in this case, McMahon v. New York, should not be confused with the Court’s other, similarly brief shadow docket decisions that allowed Trump to unilaterally fire tens of thousands of federal workers, ship noncitizens to dangerous countries without meaningful process, remove independent agency officials without cause, purge the military of trans people, and turn over your private data to a teenager named Big Balls. I want to stress that this is not an exhaustive list of recent cases in which the conservatives have given their favorite president permission to rewrite the law as he sees fit, but I have to end this paragraph sometime.

In her dissent for the three liberals, Justice Sonia Sotomayor sounded as if she still could not believe the hamfisted scheme the majority was sanctioning. By taking Secretary of Education Linda McMahon at her word that she is merely “reorganizing” the department by firing more than 2,000 of its employees, Sotomayor wrote, the Court had “handed the Executive the power to repeal statutes by firing all those necessary to carry them out.” She concluded: “The majority is either willfully blind to the implications of its ruling or naive, but either way the threat to our Constitution’s separation of powers is grave.”

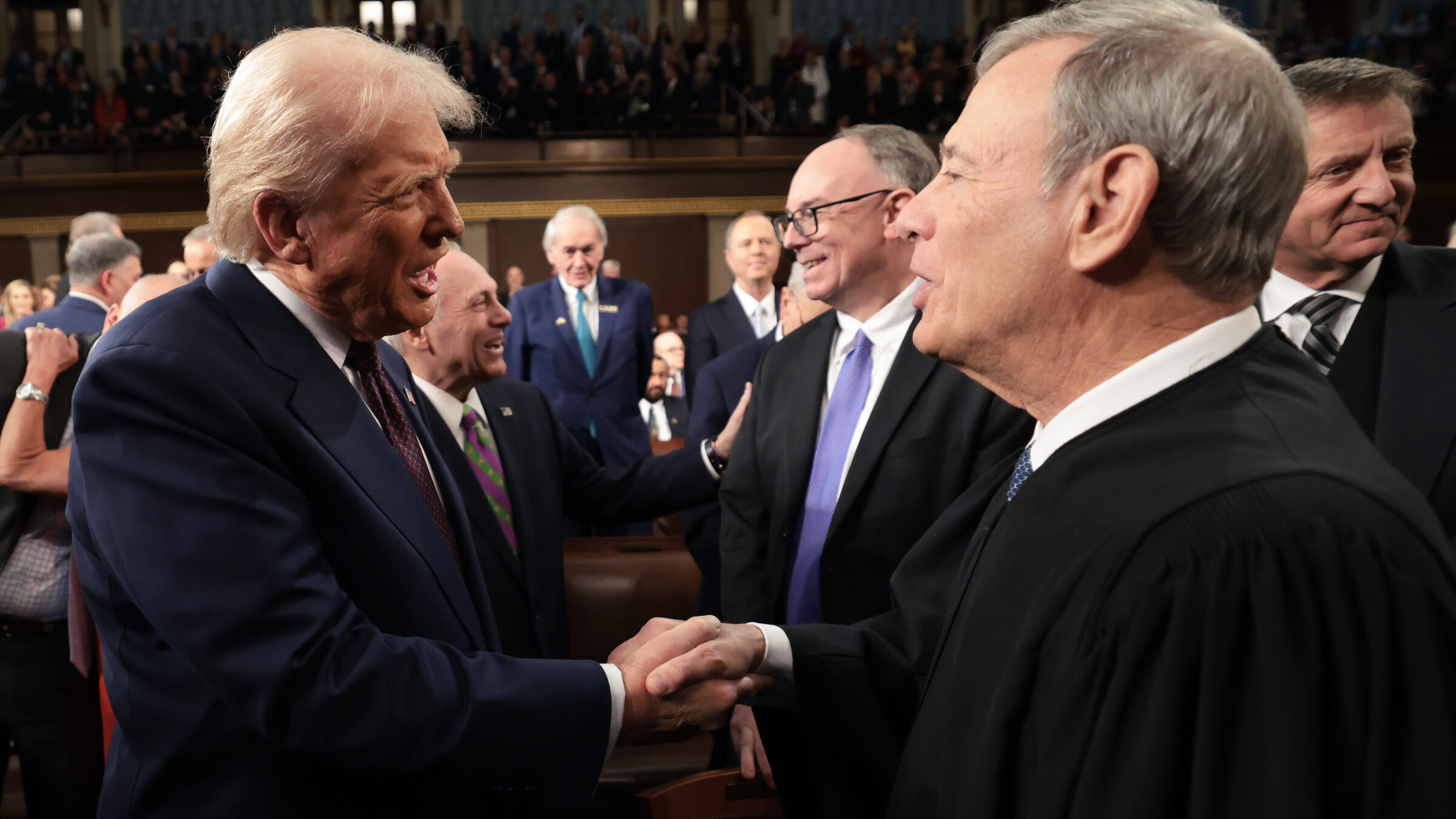

Given how gleefully the Court has spent the first few months of the second Trump administration rolling over and showing its belly at his request, it is already challenging to remember that during the first Trump administration, the Court occasionally expressed unease with the White House’s ungainly attempts to translate contemptuous lawlessness into erudite legalese. At the time, the alliance between establishment conservatives, evangelical Christians, Make America Great Again sycophants, and terminally online racists was still new and relatively fragile. Both Trump and Chief Justice John Roberts viewed themselves as the true leaders of the American right, and the presence of the other as a sort of momentary inconvenience.

(Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

But to the extent that the Court was once reluctant to endorse every stupid, lazy legal argument the Trump White House coughed up, it is not anymore. The five-justice conservative majority of Trump’s first term is now a six-justice conservative supermajority whose members, like all Republicans who are still relevant in Republican politics, have spent the past eight years fully acclimating to their roles as obedient Trump supplicants. To them, every hour that Mister Trump cannot implement their shared policy agenda is a dire legal emergency, and no task is more urgent than giving him everything he asks for, and apologizing for whichever extremely rude district court judge had the temerity to temporarily rule otherwise.

And by shunting so many of his biggest asks to the shadow docket, where the Court decides cases with minimal briefing and no oral argument, the Republican justices have replaced the tradition of explaining Supreme Court holdings in written opinions with the simple exercise of counting to five. It is as insulting as it is cowardly: At last, the conservative justices have the power to do whatever they want, but they are still too chickenshit to sign their names to it.

In her dissent in McMahon, Sotomayor ticks through the mountains of evidence that Trump’s “reorganization” of the Department of Education is a barely-disguised effort to destroy it by executive fiat. On the campaign trail, he promised to “close up” and “eliminate” the department, and to do so “early in the administration,” or possibly “immediately,” and without seeking the consent of Congress. When he announced McMahon’s nomination, he told her that her assignment was to “put herself out of a job”; on her first day in office, McMahon described “the elimination of bureaucratic bloat” as the department’s “final mission.” For whatever reason, the six conservatives decided that none of this information was worth discussing, in the context of the very basic question of whether Trump sincerely believes he is following the law, or simply bet that his ideological allies would let him get away with breaking it.

Previous iterations of the Court, even under Roberts, were not always as willing to appear this credulous in public. During legal challenges to Trump’s Muslim ban, for example, White House lawyers understandably struggled to argue with a straight face that the president’s explicit call for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” was not unambiguous evidence of his anti-Muslim animus. (Further complicating matters: Trump’s proud use of the term “Muslim ban” when describing the policy, and his public complaints that revised versions, which his administration issued in response to initial court losses, were too “watered down” and “politically correct.”) The Supreme Court eventually upheld the ban in Trump v. Hawaii, but only after the White House finally cranked out a version that was subtle enough about its Islamophobia to secure Justice Anthony Kennedy’s coveted endorsement.

The Trump administration fared less well in Department of Commerce v. New York, a case in which a splintered Court found that Trump’s proffered rationale for adding a question to the 2020 Census about U.S. citizenship—that his government needed this information in order to better enforce the Voting Rights Act—“seemed to have been contrived.” Roberts wrote the majority opinion, which ultimately allowed legal challenges to the citizenship question’s inclusion to proceed. Even for him, the notion that a Republican president would be interested in enabling nonwhite people to participate in democracy was too farcical to even pretend to take seriously.

(Photo by Chen Mengtong/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images)

The rise of the Court’s shadow docket, however, has relieved Roberts and company of the burden of feeling obliged to show their work. During the Biden administration, “emergency” relief was a tool for blocking aspects of the president’s agenda with which the conservative justices did not personally agree; under Trump, it is a rubber stamp for every challenged policy that comes before them. This is barely an exaggeration: As the law professor Steve Vladeck points out, since April 4, the Court has ruled 15 times on “emergency” applications for relief from the White House. The White House has won all 15 times. The justices wrote majority opinions in just three of the cases. In seven, including McMahon, they provided no explanation at all.

To be clear, I am not saying that the justices who decided Trump v. Hawaii and Department of Commerce v. New York would not have eventually reached the same result in McMahon. Republican justices are always going to bend in favor of Republican presidents. Again, Trump eventually got his way on the Muslim ban, and he only lost the relevant question in the Census case by a 5-4 vote.

What I am saying is that the manner in which the Court decided McMahon—a perfunctory order granting the government’s application for a stay of a lower court order, pending further developments at the First Circuit and (if applicable) the Supreme Court—should be understood as a humiliating abdication of the grand constitutional role the justices imagine themselves to fill. As bad as McMahon is, over the last two centuries, the Court has done lots of things that are just as weighty and/or heinous as imbuing the president with the constitutional authority to nuke Cabinet-level departments with the stroke of a pen. But when it did so, the Court used to at least feel compelled to write more than a single fucking paragraph in its own defense.

Trump’s crusade against public education is not new; it is the culmination of a decades-long conservative project in which the justices, through cases they hear on their merits docket, are frequent, active participants. I promise you that in private, the Republican justices cheered when they read Trump’s edict, and again yesterday when they cleared the way for him to implement it. For a gaggle of sanctimonious lawyers who otherwise cannot shut up about the importance of their solemn duty to Say What The Law Is, this should be profoundly embarrassing stuff. But they had the votes to get the result they wanted. Why bother with doing extra work?