Brian Umphress is a state court judge in Jack County, Texas, who in the year of our Lord 2025 still refuses to officiate same-sex marriages. Umphress says that he opposes Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 Supreme Court decision that recognized marriage as a fundamental right, “not only on account of his Christian faith, but also because same-sex marriage remains illegal under the laws of Texas.” The fact that same-sex marriage remains legal under the supreme law of the United States apparently didn’t factor into his decisionmaking.

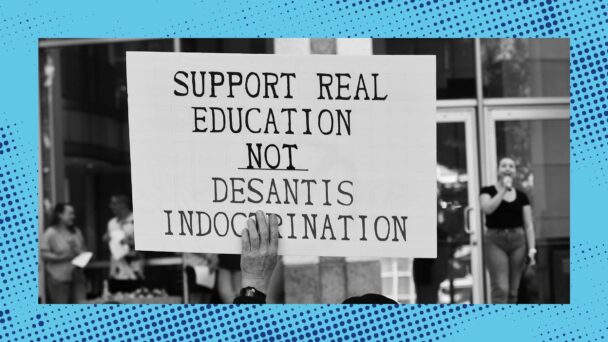

The Texas State Commission on Judicial Conduct has not disciplined Umphress for any of this. Yet he is now suing the Commission, arguing that he has a constitutional right to not officiate same-sex marriages, and that same-sex couples do not have a constitutional right to get married. His case, Umphress v. Steel, aims to shore up legal protections for judges who will officiate marriages “only for opposite-sex couples,” empowering state actors to selectively withdraw fundamental rights. Umphress’s lawsuit is part of a broader conservative project to erode the legitimacy of Obergefell and undermine marriage equality nationwide.

As a general rule (in theory, anyway), courts will only hear a case if a plaintiff alleges that they experienced an actual injury that the defendant caused and a court can fix. So when Umphress filed a complaint in federal court in 2020, Judge Mark Pittman dismissed the case. Pittman, a Trump appointee, wrote that federal courts will eventually need to resolve “an actual controversy” in which the fundamental rights to marriage and religious freedom are in conflict. But here there was no such controversy, he concluded, and “no credible indication that there will be.”

Umphress then appealed and found a friendlier audience at the Fifth Circuit. Why? Because back in 2019, the Commission issued a public warning to a different judge in a different county for similar conduct, finding that her refusal to perform same-sex weddings cast doubt on her capacity to act impartially. The Commission withdrew the warning last year, and in its briefs in Umphress’s case, the Commission “expressly and exhaustively” stated it had “no plans” to discipline him. Even so, in an unsigned opinion, a three-judge Fifth Circuit panel concluded that there is “a substantial threat” that the Commission would take enforcement action against Umphress, and that he was thus entitled to their protection.

The panel also declared that the case turned on an unanswered threshold question of state law. The state’s judicial code of conduct generally prohibits judges from engaging in extrajudicial activities that “cast reasonable doubt” on their capacity to “act impartially as a judge.” And, the Fifth Circuit said, state courts need to decide whether Texas judges violate this provision by “publicly refusing to perform same-sex weddings on moral or religious grounds while continuing to officiate at opposite-sex weddings.”

Like many states, Texas allows federal appellate courts to “certify” underlying questions of state law to the state supreme court for it to decide. So, the Fifth Circuit sent the question to the Texas Supreme Court, and it did so in a way that tees up industrious litigants to go wild: “We disclaim any intention or desire that the Supreme Court of Texas confine its reply to the precise form or scope of the question certified,” the panel wrote. In other words, Texas’s supreme court is free to facilitate Umphress’s war on marriage equality, and even though Umphress got his case thrown out of federal court, he is free to keep attacking equal rights in state court, all the while claiming the real victim here is him.

(Photo by Astrid Riecken For The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Unsurprisingly, Umphress’s requests to the state court go beyond protection from professional discipline: He also asks it to hold, as a matter of state law, that state judges are allowed to officiate weddings for only different-sex couples. His brief, filed in July, is dedicated to rehashing arguments against Obergefell itself, and insisting that same-sex marriage is still illegal in Texas. Basically, Texas still has laws on the books prohibiting same-sex marriage, Obergefell nullified those laws, and Umphress is trying to nullify Obergefell.

“Some judges may think it justifiable to flout Texas’s marriage laws if they agree with Obergefell‘s assertion that same-sex marriage is a constitutionally guaranteed right,” he writes. But he contends that judges who find the ruling unpersuasive may rightfully refuse to marry same-sex couples “solely as a matter of legal obligation, as Obergefell did not (and cannot) alter Texas’s marriage laws, and there are no injunctions or court rulings that require Texas wedding officiants to violate the state’s marriage laws or perform same-sex weddings upon request.”

Umphress also expresses resentment at the idea that the Commission would treat judges “politely and respectfully” refusing to marry same-sex couples as “something akin to racism.” The brief takes pains to distinguish disapproval of “homosexual conduct” from disapproval of “homosexual litigants,” even breaking out the old quote, “Hate the sin and not the sinner.”

This argument builds on the offense long taken by conservatives at the notion that their opposition to marriage equality makes them homophobes. In Chief Justice John Roberts’s Obergefell dissent, for example, he lamented that the decision would prompt “assaults on the character of fairminded people.” Justice Sam Alito also raged that people would “vilify” religious objectors to equality as “bigots.” And Alito joined a similar opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas five years later when the Court declined to take up an appeal from Kim Davis, a county clerk in Kentucky who is still fighting to deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples. “Since Obergefell, parties have continually attempted to label people of good will as bigots merely for refusing to alter their religious beliefs in the wake of prevailing orthodoxy,” said Thomas.

Umphress’s ongoing attempt to insulate judges who refuse to officiate same-sex weddings from the abstract possibility of professional discipline and social opprobrium is one of many avenues that the conservative legal movement is taking to reach the same destination: overturning Obergefell. Activists on and off the bench still maintain that the Supreme Court was wrong to constitutionalize gay marriage. And they are cooperating to literally set things straight.