Traditionally, when asked in public settings to talk about how they do their jobs, Supreme Court justices have spent a lot of time extolling the virtues of stare decisis—the principle that judges follow precedent when deciding new cases, in order to promote stability in the law across courts and over time. Stare decisis is a foundational part of the American legal system, so Supreme Court justices, who have spent their lives rising to the very top of that system, are expected to treat it with an appropriate amount of reverence.

In particular, the justices are supposed to express staunch disapproval of the notion that the Court would (or should) overturn precedent simply because five members think the prior decision is wrong. In a 1991 opinion, then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist lauded stare decisis for promoting “the evenhanded, predictable, and consistent development of legal principles,” and contributing to the “actual and perceived integrity of the judicial process.” Upholding precedent, he continued, is “usually the wise policy, because, in most matters, it is more important that the applicable rule of law be settled than it be settled right.”

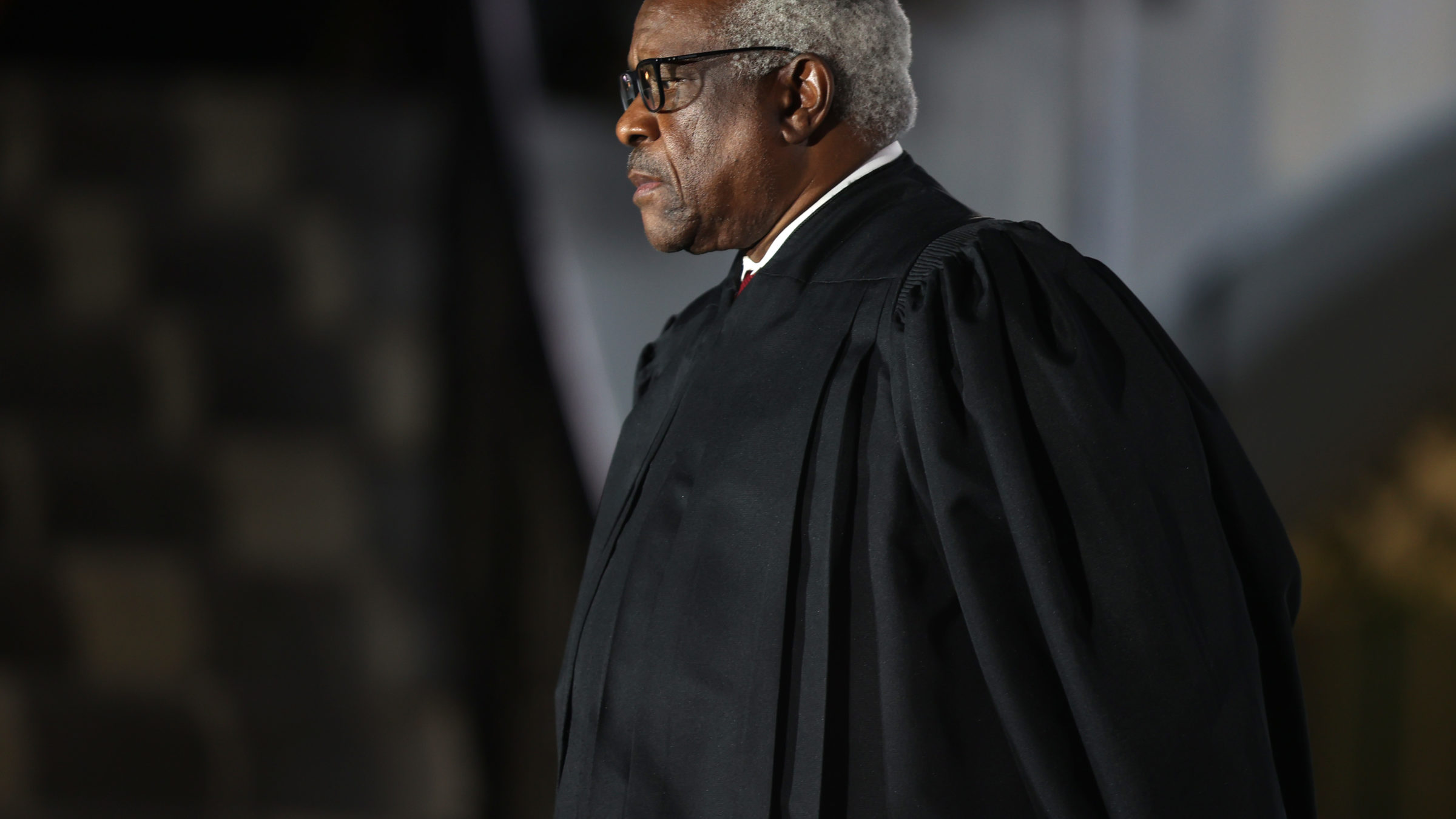

In comments last month at Catholic University’s Columbus School of Law, Justice Clarence Thomas came very, very close to dropping this charade altogether. “At some point, we need to think about what we’re doing with stare decisis,” he said. “It’s not some sort of talismanic deal where you can just say ‘stare decisis’ and not think—turn off the brain, right?” If a result is “totally stupid,” he continued, “you don’t go along with it just because it’s decided.”

Thomas was careful to note that he still gives “perspective” to precedent. But he also said he doesn’t think precedent is “the gospel,” and he analogized judges who overemphasize stare decisis to train passengers who are unaware that if they were to check the engine room, they would “find it’s an orangutan driving.” In Thomas’s view, to be worth upholding, Supreme Court precedent must be “respectful of our legal tradition, and our country, and our laws, and be based on something—not just something somebody dreamt up and others went along with.”

(Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

It has always been the case that justices emphasize stare decisis when they want to uphold a precedent, and downplay stare decisis when they want to overrule it. But Thomas’s comments are part of a rapid transformation in the willingness of the conservative justices—particularly since Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation in 2020 yielded the current six-justice conservative supermajority—to candidly discuss their power to implement their policy agenda by judicial fiat.

As recently as a couple years ago, at least professing respect for settled law was universally understood as an important part of the job. Now, Thomas and company are more willing than ever to emphasize that, whatever the pros of upholding precedent might be, they have plenty of excuses to set it aside whenever they have the votes.

At his confirmation hearings in 2018, Brett Kavanaugh dealt with a steady stream of questions from Democratic senators who feared that his confirmation would put Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey on life support. But under oath, he said all the right things: Because the Court decided Roe and reaffirmed it in Casey, he said, Casey was not just precedent, but “precedent on precedent.” He described stare decisis as “rooted in the Constitution” and “not a matter of policy to be discarded at whim,” and added that the fact that a precedent is older—Roe was decided in 1973—“does ordinarily add to the force of the precedent, and make it an even rarer circumstance where the Court would disturb it.”

Even if a prior decision was “grievously wrong,” Kavanaugh continued, that fact would not be, by itself, enough for the Court to overturn it. Instead, the justices would move on to considering the factors in favor of overruling the decision—factors that “if faithfully applied,” he said, would ensure that departures from stare decisis remain “rare.”

Four years later, Kavanaugh was ready to discuss his obligations using considerably more flexible language. “As I’ve looked at it,” he said at oral argument in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, “history tells a somewhat different story than is sometimes assumed” about stare decisis. “Some of the most important cases” in the Court’s history, Kavanaugh pointed out, involved overturning “seriously wrong” precedent—for example, Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 case in which the Court overturned Plessy v. Ferguson and struck down racial segregation in public schools.

(Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

His argument was neither subtle nor smart. By invoking Brown, Kavanaugh laid the groundwork for framing his vote to overturn “precedent on precedent” as a noble act of judicial courage; after all, if the Brown Court hadn’t overruled Plessy, Kavanaugh said, “the country would be a much different place.” When the Court issued its opinion in Dobbs in 2022, Kavanaugh wrote a concurrence in which he marshaled some numbers to portray his flip-flop as routine and unremarkable: “Every current Member of this Court has voted to overrule precedent,” he wrote, as had “every one of the 48 justices appointed to this Court” over the previous century. Strangely, he decided that the real-world differences between the Court striking down racial segregation in schools and the Court striking down protections for reproductive autonomy did not merit further discussion.

After her nomination in 2020, Barrett, too, knew exactly what to say when asked about the fate of Roe. When asked by South Carolina Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, Barrett affirmed that the Court has a “very rigorous process” for deciding when to overturn precedent—a process that requires the justices to consider “many factors,” including the public’s reliance on the interests a Supreme Court decision protects.

Unlike Kavanaugh, Barrett did not write separately in Dobbs to reconcile her vote with her earlier comments. That said, in her recent book, Listening to the Law, Barrett drops a hint about how she might have done it: Although the Court doesn’t overturn precedent “lightly,” she writes, it “can and does fix mistakes.” She also brought some data to bear, noting that “the Roberts Court, of which I am a part, has overturned precedent roughly once per term.” This is true, but it omits the obvious facts that she only joined the Roberts Court five years ago, and that the precedents her confirmation enabled the Roberts Court to overturn just happened to be precedents the conservative legal movement had fought for decades.

Outside of Thomas, probably no conservative justice is more enthusiastic about reimagining stare decisis than Justice Samuel Alito, who in his Dobbs majority opinion argued that stare decisis could not save a case as “egregiously wrong” and “exceptionally weak” as Roe. But during his confirmation hearings in 2006, even Alito knew to stick to conventional talking points, calling Roe an “important” precedent and lauding stare decisis as a “fundamental part of our legal system” that “limits the power of the judiciary” and “reflects the view that courts should respect the judgments and wisdom that are embodied in prior judicial decisions.” As it turns out, all Alito needed in order to see Roe differently was the power to cast one of five votes to get rid of it.

(Photo by Ken Cedeno/Corbis via Getty Images)

Again, the extent to which a Supreme Court justice considers stare decisis important correlates strongly with how badly that justice wants to overrule a precedent. But what Thomas’s recent comments reveal is how comfortable the conservative justices have become with admitting that “stability” or “consistency” in the law was never especially important to them in the first place. Between Dobbs and Students For Fair Admissions and Loper Bright Enterprises and Rucho and Janus and so on, this conservative supermajority has transformed overturning landmark Supreme Court cases into a regular occurrence. The notion that responsible justices respect the work of their predecessors has been replaced with a sort of free-floating authority to invent new ways to stuff it in the garbage.

Thomas joined Alito’s opinion in Dobbs, which held that the Due Process Clause does not protect the right to abortion care. But he also made clear that he would have gone even further: In a concurrence, Thomas argued that any Supreme Court precedents recognizing a substantive due process right—including those that protect contraceptive access, sexual privacy, and marriage equality—are “demonstrably erroneous,” and he called on the Court to “reconsider all” of them at its “earliest opportunity.”

At the time, no other justice joined Thomas’s opinion. But in the three years since, this conservative supermajority has only grown more ambitious, and less interested in maintaining the institutional checks that they used to swear they would take seriously. They do not view precedents with which they disagree as entitled to their respect, but as errors that they have a solemn duty to fix.