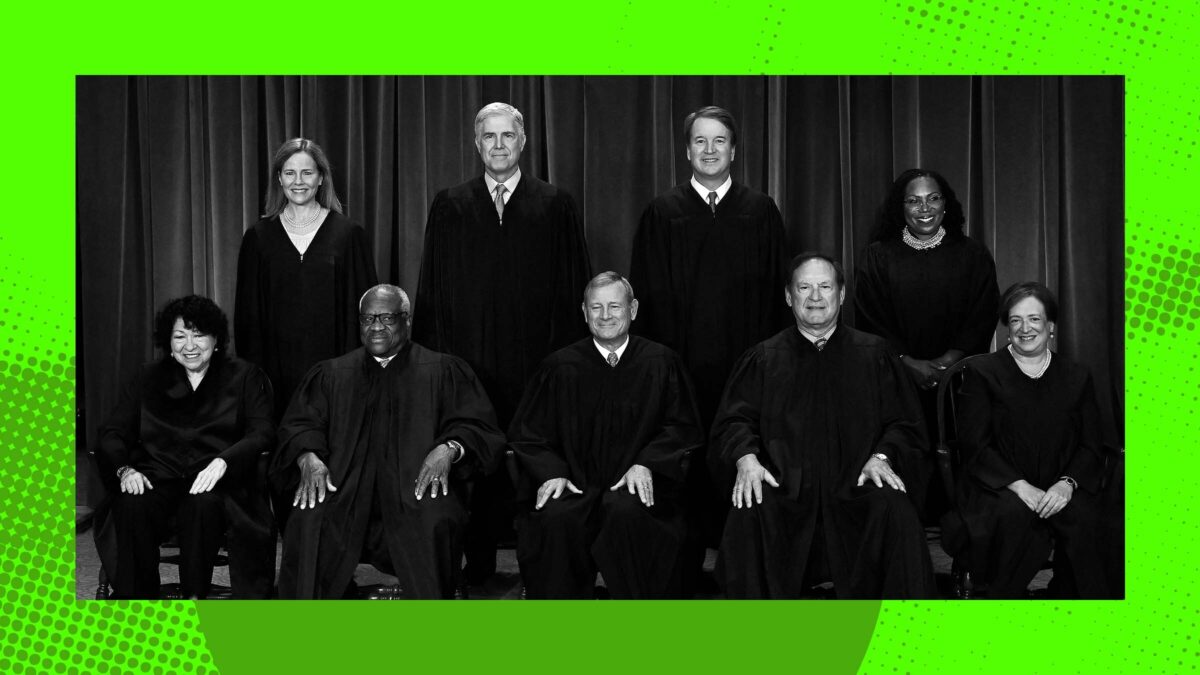

Two weeks ago, a federal district court declared Texas Republicans’ proposal to redraw the state’s congressional districts to be an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, and blocked it from taking effect. On Thursday evening, the Republican majority on the Supreme Court reimposed that map, which will allow the state to use it in the 2026 midterm elections. As a direct result of this decision, Republicans could win five additional seats in Congress, to which President Donald Trump has claimed his party is “entitled.” The three liberal justices dissented from the unsigned shadow docket order.

The decision below, which held that Texas illegally engaged in race-based redistricting, was not the knee-jerk response of some far-left partisan. Judge Jeffrey Brown, a Trump appointee, authored the 160-page majority opinion after a nine-day hearing featuring 23 witnesses and thousands of exhibits. After assessing the credibility of the witnesses and evaluating the extensive record before them, Brown and Judge David Guaderrama reached a simple conclusion: “Substantial evidence shows that Texas racially gerrymandered the 2025 Map.”

District courts have a unique role in the legal system: They are the ones actually tasked with finding the facts. And under the Court’s own precedent, appellate judges are supposed to defer to a district court’s factual determinations about “whether racial considerations predominated in drawing district lines,” unless the district court’s findings are the product of “clear error.”

This is a demanding standard—not a “if it were me, I wouldn’t have done it like that” standard, or a “but I don’t like that result” standard, or a “but I was really hoping Republicans would keep their majority in the House next year” standard. Rather than apply it, which would have meant respecting both the lower court’s conclusions and voters of color as equal members of the political process, the Court opted to perform its own made-up analysis of its own made-up facts.

Abbott v. League of United Latin American Citizens is the Supreme Court’s latest rejection of a district court’s comprehensive fact-finding and analysis, without so much as full briefing or oral argument, upon request of Republican officials and at the expense of marginalized people. Yet again, a district court showed its work. Yet again, the Supreme Court showed its ass.

The majority opinion contends that Texas should be able to use the gerrymandered map because the district court likely “committed at least two serious errors.” First, the majority claimed, the lower court “failed to honor the presumption of legislative good faith.” This principle calls on courts to not hold “ambiguous” and “circumstantial” evidence against a legislature accused of discriminating based on race, which is illegal and bad, if the legislature could merely have been discriminating based on partisanship, which is legal and fine. (As some of you surely heard over Thanksgiving, assuming someone did something racist is just as bad as racism, if not worse.)

Second, the majority said the lower court “failed to draw a dispositive or near-dispositive adverse inference” against the map’s challengers, because “they did not produce a viable alternative map that met the State’s avowedly partisan goals.” This is a fairly new idea—and, apparently, requirement—that the Court has surfaced in recent redistricting cases. Basically, it means that someone alleging that lawmakers created a racial gerrymander must show that lawmakers could have made an alternative map that secured the same partisan advantage, but without the alleged racism. Otherwise, the Court is more inclined to assume that the legislature was acting in good faith. Put together, the majority argued that the district court should have just assumed better things about Texas Republicans, and worse things about the League of United Latin American Citizens.

Justice Samuel Alito authored a concurrence, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, that stressed that race had nothing to do with Texas’s new map. According to Alito, it is “indisputable” that Texas Republicans adopted the map for “partisan advantage pure and simple.” Alito also emphasized that it is “critical” for challengers to “disentangle race and politics” by producing a just-as-good partisan map. “Because of the correlation between race and partisan preference, litigants can easily use claims of racial gerrymandering for partisan ends,” he wrote. The obvious corollary—that states can easily use racial gerrymanders for partisan ends—featured no part in his thinking.

The majority opinion and Alito’s concurrence suffer from the same analytical deficiencies. First, they ignore the fact that any assumptions that courts make—whether presumptions about the legislature’s intent or the strength of the challengers’ case—can be overcome with facts and evidence. And second, they ignore the simple reality that district court judges—not the justices on the Supreme Court—are the people best-positioned to review that evidence.

The district court determined that considerable direct evidence overcame these presumptions. In this opinion, the Supreme Court replaced those facts with what a majority of its justices preferred to believe. What legal basis did it have for doing so? Writing for the liberals in dissent, Justice Elena Kagan provided a short answer: “It has none.”

The Court’s order reimposing Texas’s racial gerrymander is best explained not by legal principle, but partisan preference and political power. The Republican justices ruled as they did because they want to help their allies. For them, multiracial democracy is not a core constitutional commitment, but a gift to bestow upon minorities when Republicans find it convenient.