In 2008, a New York state court sentenced Angel Ortiz to ten years in prison for robbery and attempted sexual abuse. While he was incarcerated, he earned a 17-month early release with “good time” credits that the state awards for good behavior. Instead of gaining his freedom, however, Ortiz remained in the same cell for the entire duration of what should have been his early-release period. Then, even after Ortiz completed his full sentence, the state still refused to release him from its custody. For eight more months, he was held in conditions largely identical to those in which he’d been incarcerated all along.

New York claims all of this is perfectly legal and okay because Ortiz was unable comply with a state law that bars people convicted of a sex offense from living within 1,000 feet of a school. In a city as dense as New York City, where Ortiz spent most of his life, obtaining compliant housing is basically impossible. Last month, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with New York’s position, denying his request for review in Ortiz v. Breslin with a single sentence.

Upon becoming eligible for early release, Ortiz had suggested multiple residences for himself, including the apartment shared by his mother and daughter and, in the alternative, several shelters. But only a few shelters complied with the law, and they maintained long waitlists because, as it turns out, many people are in Ortiz’s predicament. With nowhere else to go, the state transferred him to a “residential treatment facility,” where he lived with the general prison population behind barbed wire well after his sentence had ended. As his lawyers put it, Ortiz was stuck in a “Kafkaesque trap” in which the state required him to find housing that the state also made it impossible for him to obtain.

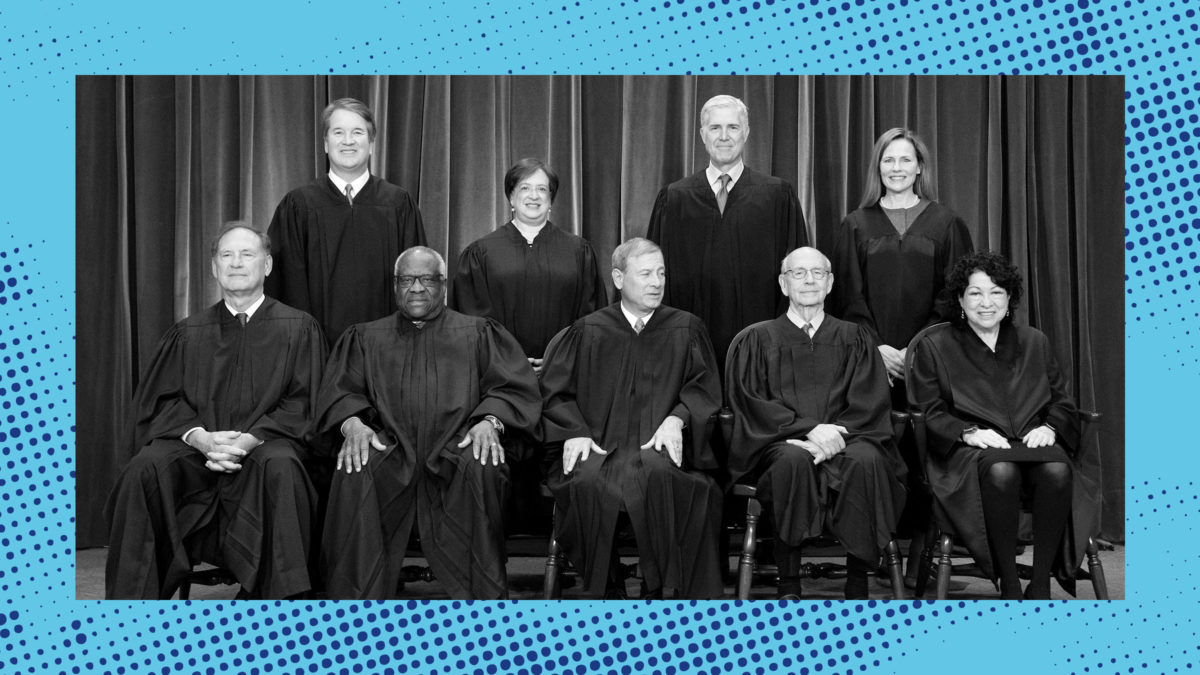

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a critical statement—not quite a dissent—about the Court’s decision to deny review, calling out the “serious constitutional concerns” with the law. “Rather than tailor its policy to the geography of New York City or provide shelter options for this group, New York has chosen to imprison people who cannot afford compliant housing past both their conditional release date and the expiration of their maximum sentences,” she wrote, calling on the state to “choose to reevaluate its policy in a manner that gives due regard to the constitutional liberty interests of people like Ortiz.”

However, Sotomayor’s statement fell short of indicting the judiciary for its role in enabling Ortiz’s wrongful incarceration. She noted that “legislatures and agencies are often not receptive to the plight of people convicted of sex offenses,” and reiterated the importance of judges stepping in to aid members of marginalized communities. But courts failed Ortiz at least as often as the electorally accountable branches of government. He challenged his conviction up to the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court; at every level, judges denied him relief. Her colleagues at the Supreme Court rescheduled their consideration of his case a dozen times before ultimately turning him away.

Criminalizing people for a status or chronic condition, like addiction or mental illness, is something that the Constitution does not allow. In 1962, for example, the Court struck down a California law that criminalized being addicted to narcotics, and that allowed the state to bring a prosecution against someone “at any time before he reforms.” Allowing such a law to stand “would doubtless be universally thought to be an infliction of cruel and unusual punishment,” wrote Justice Potter Stewart for a six-justice majority. In coming to that conclusion, Stewart recognized addiction as like any other illness contracted involuntarily. “Even one day in prison would be a cruel and unusual punishment for the ‘crime’ of having a common cold,” he wrote.

The Court hasn’t yet ruled on whether residency restrictions, or other state and local laws that target people experiencing homelessness, similarly criminalize a status. Yet in her statement, Sotomayor highlighted the expert consensus that residency restrictions like New York’s do nothing to reduce recidivism, citing research suggesting that such laws may increase the likelihood of homelessness, unemployment, and isolation—all of which are conditions that make reoffending more likely. Multiple courts have struck down residency laws on this basis already. “No one doubts that New York’s goal of preventing sexual violence toward children is legitimate and compelling,” she wrote. “But New York nonetheless must advance that objective through rational means.”

Sotomayor chalked up the Court’s treatment of Ortiz to the lack of a “clear split” between federal appeals courts on this issue. (A split occurs when lower courts rule differently on the same legal question and is one criterion weighing in favor of granting review.) But the truth is that the Court doesn’t have rigid criteria for granting certiorari, and has total control over its docket. Nothing but indifference stopped Sotomayor’s colleagues from stepping in.

Ortiz is not the only person who has endured wrongful incarceration because of this law. As his lawyers noted, thousands have experienced the same treatment since 2015, and the state was expected to incarcerate at least 250 more people beyond their release dates just last year. Still, the justices can’t be bothered to intervene, even as they embrace, for example, stale challenges to environmental regulations that are literally no longer in effect. This Court is far more preoccupied with protecting the liberty interests of people like fossil fuels producers than it is with protecting the liberty interests of indigent people convicted of crimes. In the eyes of these justices, some people matter, and some do not.