Editor’s note: This month, we’ll be taking a closer look at some of the most consequential cases the Supreme Court—the most conservative Supreme Court in a century—will decide in its upcoming term. Today: Merrill v. Milligan, a case about whether racial gerrymandering is still illegal, or whether it’s totally fine for Republican-controlled legislatures to concoct legislative maps that draw Black people out of existence.

Alabama is home to 1.3 million Black people—one of six states with the country’s highest proportions of Black constituencies—but numbers don’t necessarily translate to political might. While Black people constitute 27 percent of the state’s population, according to the 2020 census, a federal trial court found that Black Alabamians only have “meaningful influence” over 14 percent of its U.S. congressional seats, and the state has only one majority-Black district. And that may be no accident.

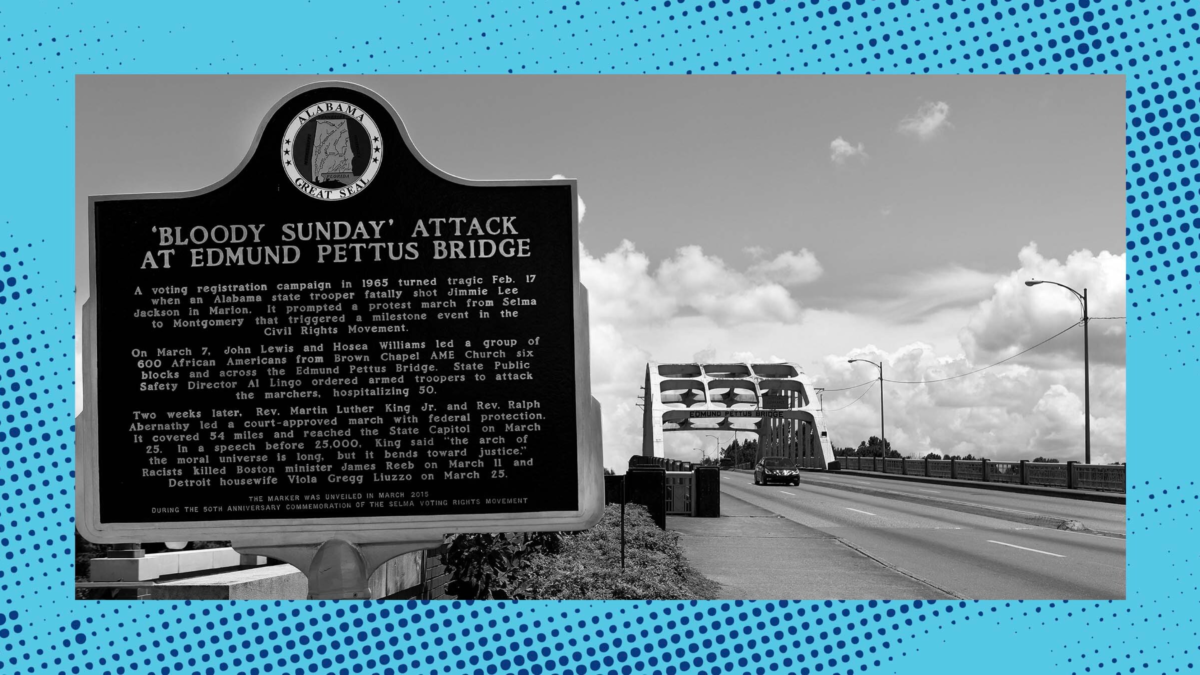

Next term, the Supreme Court will hear Merrill v. Milligan, a case about whether the GOP-controlled Alabama state legislature attempted to dilute the voting power of the state’s “Black Belt” by drawing up a discriminatory 2021 congressional redistricting plan. The two sides are arguing over whether the map violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (“VRA”), which prohibits racial discrimination in voting practices or procedures. At the heart of the case is whether the former Confederate state’s long history of suppressing the Black vote persists—and, if so, whether a majority in the Court are willing to accept that as a reality.

The voters and civil rights groups who challenged the maps claim that the Alabama legislature “packed” and “cracked” Black voters into one gerrymandered U.S. House of Representatives district out of the state’s seven. “Packing” refers to grouping as many voters as possible into as few districts as possible, and “cracking” describes splitting a target voter group into different districts. The most contentious area in Alabama’s redistricting saga is the Black Belt, a region where white settlers enslaved hundreds of thousands of Black people on cotton plantations.

In January 2022, an Alabama district court ruled in the voters’ favor, noting that “no Black person has won a statewide race in a generation,” no Black candidate has ever won a majority-white congressional district, and most Black state legislators in office at the time were elected by majority-Black districts. It then barred the proposed maps and ordered the legislature to produce maps with two majority-Black districts, “or something quite close to it.”

Photo by Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Typically, the next stop for this case would be a federal appeals court. Generally, the Supreme Court only considers questions that a federal appeals court hasn’t when the question is of “imperative public importance,” according to the 1925 Judiciary Act. But in January, the Supreme Court made the extraordinary move of bypassing the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals and granting Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill a stay of the district court’s order on the shadow docket. Merrill claimed that voters would be “irreparably harmed” by the order, because upcoming elections would be based on “district lines that never would or could have been drawn but for sorting Alabamians on the basis of race alone.” Somewhat preposterously, a majority of the Court held that a map that does not dilute Black votes would cause irreparable harm to the state’s voters.

Because of the Court’s order, Alabama’s May primary election proceeded with the maps that a trial court ruled diluted Black voter power. The Court used its emergency powers to allow the GOP to use a racially-gerrymandered map and it didn’t bother to explain to the public why doing so was of imperative importance. On October 4, the Court will hear oral arguments to decide if the GOP’s proposed maps violated the VRA, and which redistricting maps—the lower court’s or theirs—Alabama will use going forward.

Chief Justice John Roberts dissented from the stay, stating that “the District Court properly applied existing law in an extensive opinion with no apparent errors for our correction.” Separately, Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Stephen Breyer also dissented, but went further than a technical disagreement and chastised the majority for effectively revising VRA precedent by overturning a lower court order that complies with the Supreme Court’s past racial gerrymander cases. And the justices did this with “the scanty review this Court gives matters on its shadow docket,” Kagan wrote. She cited her dissent in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee to note that for the Court to reverse such a decision without explanation is “a ruling that undermines Section 2 and the right it provides.”

While Roberts dissented, he also agreed with the majority’s decision to hear the full case because he claimed the VRA precedent has “engendered considerable disagreement and uncertainty regarding the nature and contours of a vote dilution claim.” This seemed to be in keeping with Roberts’ skepticism of contemporary Black voter suppression. In another 2013 case on voting rights in Alabama, Shelby County v. Holder, the Court dismantled the provision of the VRA that required states with histories of suppressing the votes of people of color to seek approval from the federal government before passing new elections-related legislation. “Things have changed dramatically,” Roberts wrote, as “voter turnout and registration rates now approach parity” in previously-regulated counties. He cited a congressional report which found that “there has been approximately a 1,000 percent increase since 1965 in the number of African-American elected officials in the six States originally covered by the Voting Rights Act.”

One way of interpreting the change in Black voter participation after the passage of the VRA was that it was successfully doing its job, but in Roberts’ view, the statistics told a different story: that the racism the VRA was meant to ameliorate was over. The list of counties and states that had to seek approval from the federal government for elections-related laws was “based on decades-old data and eradicated practices,” he wrote. “There is no longer such a disparity.” As demonstrated in Shelby County, Roberts has a deep misunderstanding about racism in the South—one belied by almost every facet of life in the Black Belt.

Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill, a man who apparently feels very strongly about preserving racist maps (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

In Merrill, the Alabama Black Legislative Caucus submitted an amicus brief showing that white antagonism to Black political power has persisted since the state’s earliest days, particularly in the Black Belt. In 1865, the state legislature passed Black Codes, laws that facilitated the arbitrary incarceration of freed Black people and the subsequent exploitation of their labor. The federal government had to force the state to allow Black people to participate in the post-Civil War state constitutional convention. In 1868, the legislature passed a constitution that recognized the 14th Amendment, forced by Congress to do so in order to rejoin the United States. But in 1875, Alabama passed a regressive state constitution that defunded public education, mandated racial segregation in schools, and allowed for the levying of discriminatory poll taxes.

More than 130 years later, contemporary state politics bear out this legacy of segregation in both attitudes and practices. In a 2010 recording cited in the brief, Alabama senators and influential legislative allies admitted to wanting to defeat a referendum on electronic bingo partly because they believed it would prompt high Black voter turnout. “Just keep in mind if [a pro-gambling] bill passes and we have a referendum in November, every Black in this state will be bused to the polls. And that ain’t gonna help,” one political ally said. Another suggested that Black voters would be lured to the polls by “free food.” It was only last year that a majority of voters cast ballots in favor of redrafting the state constitution to eliminate passages like the one mandating racial segregation in schools.

“Alabama’s historical commitment to racial hierarchy still defines its contemporary political culture,” the brief says, quoting the book Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics. “There is no reason to expect that culture to change of its own accord.”

The Alabamian members of the Black Legislative Caucus reported their own experiences enduring the legacy of racism in state politics. In the brief, they note routine “racist commentary and disrespectful behavior—such as refusal to recognize their right to speak during debate on proposed legislation implicating the constitutional rights of Black protestors—during the course of their duties.” The legislature is almost exclusively composed of Black Democrats and White Republicans. And over the last decade, the number of Black state legislators has decreased 23 percent, even though the state’s Black population has increased more than any other racial group over the same time period. If there were one place that proves why prohibiting racially discriminatory election processes remains necessary, it just might be Alabama’s Black Belt.

Nevertheless, the conservative justices have given many indications that they believe racism is over. Almost a decade ago, in Shelby County, Roberts insisted that the racial hierarchy of the South was no longer in existence. None of this bodes well for whether the justices will accept the role of white supremacy in Alabama’s electoral process.