If your eyes glaze over when you read words like “Appropriations Clause” and “rule promulgation,” I understand. Recent Supreme Court terms have been defined by explosive rulings related to easily recognizable concerns, like “Is Sam Alito going to force me to have a kid?” and “Is Clarence Thomas going to get that kid shot?” So a question like “Is that federal agency funded correctly?” might not seem all that important or even relevant to your day-to-day life. But when the justices hear oral argument in Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Community Financial Services Association of America on October 3, that’s exactly the reaction our corporate overlords are counting on.

At first glance, CFPB v. CFSA is a case about the constitutionality of the funding scheme Congress set up for the CFPB more than a decade ago. Look again, though, and it’s revealed as a case about empowering big business over regular people, and empowering the conservative-controlled federal judiciary over elected representatives.

The CFPB is a government agency that Congress established by passing the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, in the wake of the financial crisis two years earlier. One of the agency’s many responsibilities is to make and enforce rules to protect consumers from “unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices and from discrimination.” In this case, the CFSA, a trade association of payday lenders regulated by the Bureau, is challenging a rule saying that lenders can’t withdraw loan repayments from someone’s bank account if two consecutive attempts failed due to insufficient funds. The rationale here is pretty straightforward: As the agency explained, after back-to-back failed attempts, the lender knows full well that the borrower doesn’t have the money, and all they’re doing is racking up overdraft fees the borrower cannot afford.

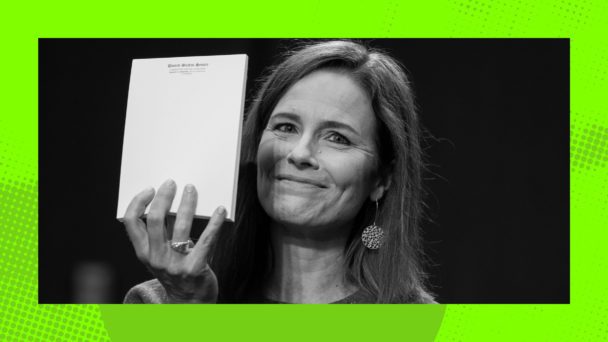

(Photo by Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Congress created the Bureau to make rules like this one, which protect some of the most vulnerable people in the country from some of its most abusive institutions. Payday lenders make short-term, small-dollar loans with disproportionately high fees relative to the principal amount. While credit cards or personal bank loans usually have annual interest rates between 10 and 30 percent, the average rate for payday loans is 391 percent, and can run as high as 652 percent in some states (I’m looking at you, Idaho.) The average payday loan borrower takes out eight loans a year of about $375 each to help cover expenses like rent and groceries, and pays over $500 in fees for the privilege. CFSA is suing so it can get back to hounding broke people for money they don’t have.

CFSA threw a bunch of arguments at the wall in its efforts to get the rule invalidated. They lost in federal district court, but at the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals—the country’s Trumpiest, most conservative federal appeals court—one of them stuck. In the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress specified that CFPB would receive a capped amount of yearly funding from the Federal Reserve System rather than rely on annual congressional appropriations. The Fifth Circuit seized on this, holding that the agency’s rule was invalid because Congress didn’t fund the agency the right way. According to the court, the Constitution requires that funds “be disbursed in accord with Congress’s dictate and Congress’s alone”—so, when Congress authorized the Bureau to receive funds directly from the Federal Reserve, it unconstitutionally “cede[d] its power of the purse to the Bureau.” The court then vacated the payday lending rule after concluding that the CFPB’s purportedly unconstitutional funding structure made CFSA “entitled to a rewinding of the Bureau’s action.”

The CFPB, as you might imagine, feels differently. It argues that the Constitution only requires Congress to authorize appropriations with a statute, and that the Dodd-Frank Act clears that bar. Congress has similarly funded numerous other agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Even Justice Antonin Scalia, patron saint of the conservative legal movement, once said that the constitutionality of appropriations like the Bureau’s “has never seriously been questioned.” Yet the Fifth Circuit concluded that it “must respectfully disagree” with every other court that has heard Republicans make this argument over the years.

This is surprising because federal courts have upheld the constitutionality of this structure at least seven times before. It’s also not surprising because the Fifth Circuit is basically the clown capitol of the conservative legal movement’s circus. If a repeatedly-rejected Republican argument was going to get a foothold anywhere, it would be in the Fifth Circuit.

By invalidating the payday lending rule based on the CFPB’s funding structure, the Fifth Circuit made this case about much more than one rule. Suddenly, all of CFPB’s rules and enforcement actions are vulnerable to invalidation by corporate cronies on the bench, as are, in theory, actions taken by other federal financial regulators funded in the same way. Scholars of financial regulation have sounded the alarm, warning the Court in an amicus brief that effectively defunding the CFPB would cause “regulatory chaos” and “stifle credit markets, destabilize banks, and likely throw the economy into recession.” And it’s not just the CFPB at stake: Since “not one federal bank regulator is funded by standard congressional appropriations,” they write, “the CFPB and its peers—and the consumers and lenders who depend on them—rise and fall together.”

Pictured L-R: future freelance loansharks? (Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP) (Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images)

Financial services companies have realized this is an opportunity: Since the lower court’s ruling, defendants in several CFPB enforcement actions have argued that the agency’s rules are invalid and their case should be dismissed. The Bureau has spent over a decade working to build up a fairer economy by reining in lenders who target poor people and people of color, mislead their customers, and keep people trapped in cycles of debt. If the Court were to bless the Fifth Circuit’s harebrained theory here, it could all come tumbling down. Such a result would also expand the authority of the judiciary, enabling judges to destabilize the economy just because they don’t like the particular way Congress authorized an expenditure.

In its briefing, CFSA tells the Court that affirming the Fifth Circuit here would enhance Congress’s oversight of the Bureau and give power to the people by “taking back the purse-strings” from the agency. In reality, the only people this would empower are the lenders exploiting millions of Americans who are just trying to get by.