At 7 A.M. on a Friday in August 2017, Michael Walker, a union representative of Teamsters Local 174, gave the cut signal—a slashing sign across his throat—to the drivers loading and unloading concrete at a Seattle facility. Negotiations over a new union contract had broken down with the ready-mix concrete company Glacier Northwest, and their old contract had expired. The union shop steward and picketing captains told 43 Glacier Northwest drivers out on concrete delivery routes to return their trucks. Forty-five minutes later, all the trucks were back at the company’s yard. The workers were on strike.

For centuries, work stoppages have been a vital tool in the kit of unions organizing for fairer work conditions. The Industrial Revolution of the mid-nineteenth century sparked an organized labor movement that opposed long work hours, safety hazards, and arbitrary (and frequent) wage cuts. Unions adopted labor reform platforms with demands to improve the lives of workers. In 1902, 147,000 coal miners successfully went on strike for five months for better pay after the federal government stepped in for the first time to mediate negotiations.

Over half a century later, half a million steel workers, as part of the largest work stoppage in U.S. history, withheld their labor for four months until they secured a contract that protected jobs, standardized hours, and increased pay. In 1994, Major League Baseball players refused to work mid-season, resulting in the World Series cancellation, over a salary cap that the league’s owners had proposed. Two years later, they got a contract without a cap.

Strikes have been essential in preserving American workers’ rights. But they may be under threat now. Last week, the Supreme Court agreed to review a case about that 2017 concrete strike, Glacier Northwest v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters. The company is arguing that the strike caused it to suffer monetary losses. The Court will decide if the company can sue to make the union pay for it.

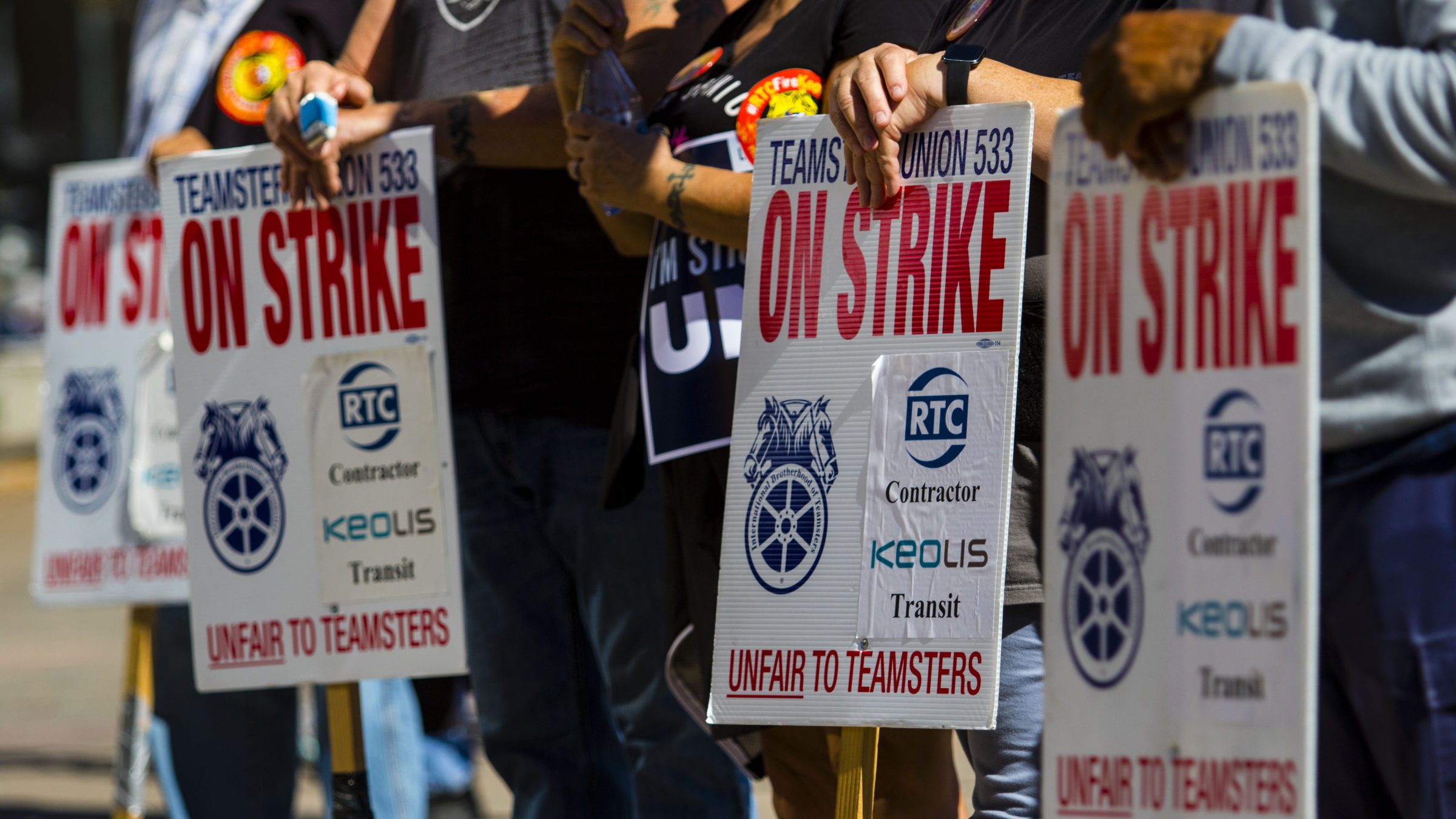

(Kevin Schafer / Contributor / Getty Images)

After the strike began, Glacier Northwest’s managers had to dispose of the undelivered concrete contained in 16 trucks to avoid damage caused by hardening concrete. The company issued disciplinary letters to these 16 drivers and then sued the union over the wasted concrete. The Teamsters Local fired back with a complaint to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), a group of commissioners who are charged with deciding workplace union disputes, claiming that the company’s lawsuit was illegally interfering with the workers’ right to unionize as established by the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). At stake now is the Board’s authority over union-related disputes and whether a work stoppage of this kind is legally protected activity—or whether megacorporations are free to sue workers for everything that goes wrong while they’re out of the job.

In defending the striking workers, the Teamsters pointed out that the employees left the trucks running “precisely so that the concrete would not harden” and to allow the company to use the concrete “as it saw fit.” They also noted that company management “failed to arrange for replacement workers or additional management personnel, notwithstanding the expiration of the collective bargaining agreement and its no-strike clause.”

Glacier Northwest maintained that of the 16 drivers who left wet concrete in trucks, only seven notified management of having done so. The company alleged that the other workers intentionally left concrete mix in the trucks so that it would harden and ruin the vehicles. According to the company, if the NLRA prohibits it from bringing this lawsuit, employers’ private property will be “at the mercy of deliberate sabotage,” and it will have “no means of just compensation.”

The Washington Supreme Court rejected the company’s lawsuit, holding that the NLRA prohibits lawsuits of this type, even if the law doesn’t outright say that. The state court relied on a Supreme Court case San Diego Unions v. Garmon, in which the justices held that an employer couldn’t sue for alleged economic losses from union picketing outside the workplace. The Garmon Court broadly defined the activity that the law protects, and said if something “arguably” constitutes union organizing and is not “violence” or “vandalism,” that dispute should be handled by the NLRB, not judges.

Glacier Northwest is trying to cast its employees’ strike as falling within that exception. But the Washington Supreme Court held that while the company’s economic losses were “unfortunate,” they didn’t amount to either “vandalism” or “violence,” since “economic harm may be inflicted through a strike as a legitimate bargaining tactic.” Glacier Northwest wants to convince the justices that it is not.

If the Court sides with Glacier Northwest, companies will be free to threaten employees with lawsuits anytime they dare to strike. In its complaint to the NLRB, the Teamsters describe the company’s lawsuit as “objectively baseless” and allege that it is using the process to gain information about the union’s strike tactics.

(Photo by Ty O’Neil/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

On its face, withholding labor often results in economic loss—that’s the very point in demonstrating the value of workers. Striking is most impactful for time-sensitive tasks. Farm workers, for example, have the most leverage in union contract negotiations when ripe crops need to be harvested. The idea that strikers destroy property when they withhold their labor is a dangerous one because it can be stretched to deter most strikes, especially the most effective ones—those that put a dent in their employers’ wallet.

There is little reason for hope that the Roberts Court will take an expansive view of labor rights in this case. It is the most business-friendly court in over a century, according to professors Lee Epstein and Mitu Gulati, who found that business litigants have won 63 percent of the cases brought before the Court since Roberts became chief justice in 2005. By extension, the Court has been no friend to unions. Last year, in Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, the Court upheld a farm owner’s private property rights over that of farmworkers’ right to unionize, striking down a California law that allowed union representatives to enter farmland to organize workers. The law restricted access to a maximum of three hours a day and when workers were off the clock. Still, the Court held that the law amounted to an unconstitutional “taking” of the farm owners’ land.

Citing Cedar Point Nursery, Glacier Northwest has appealed to the Court’s longstanding skepticism of union rights in Ross, arguing that “union organizing does not override the importance of safeguarding the basic property rights that help preserve individual liberty.” If the conservative justices agree, it will become even riskier for workers to strike, put centuries of hard-fought gains in workers’ rights on shakier ground than ever.