In the final days of his 2024 re-election campaign, President Joe Biden was preparing to do something he should have done a long time ago: announce his support for Supreme Court reform. His preferred interventions—term limits for justices and a binding ethics code—would not be nearly enough to blunt the power of the Court’s six-justice Republican supermajority. But they are also far more aggressive proposals than Biden, your favorite institutionalist’s favorite institutionalist, had ever backed before.

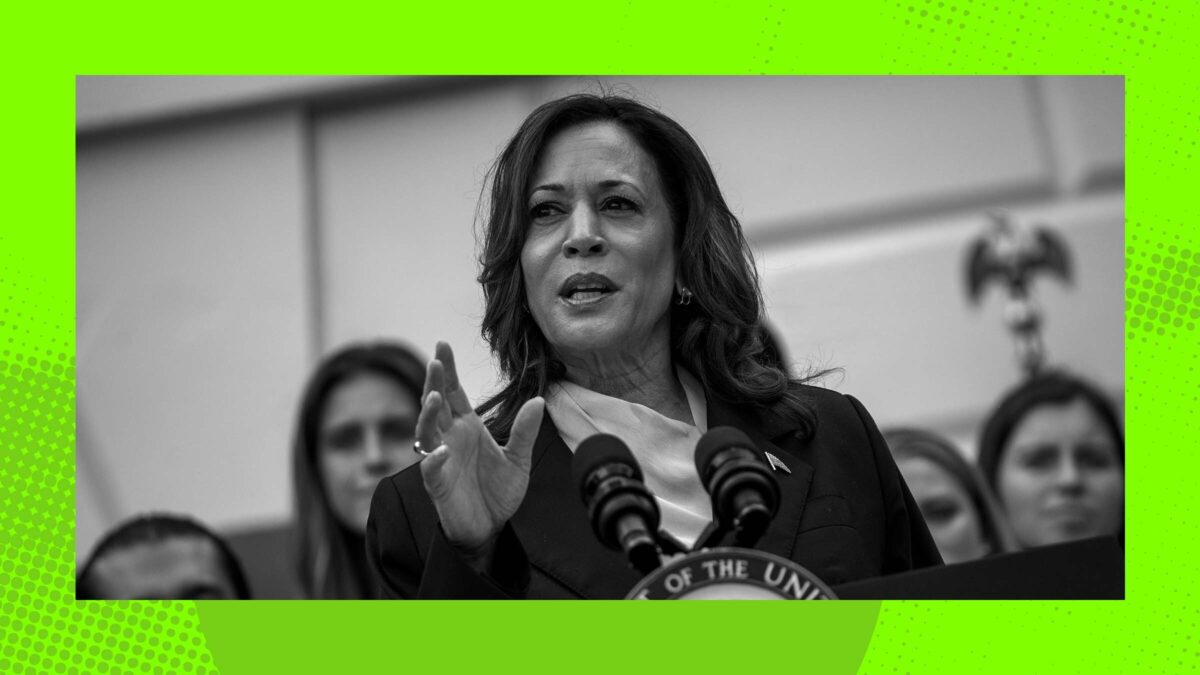

This abrupt change of heart, which came shortly before Biden announced that he would not seek a second term and instead threw his support behind Vice President Kamala Harris, also functions as a tidy encapsulation of his presidency: a good idea that, in retrospect, probably would have been better if it had happened several years earlier.

Harris, who has already locked up the Democratic nomination, now has a chance to do what Biden wouldn’t or couldn’t: make the case to voters that the Supreme Court as it exists today is beyond saving, and build (even more) public support for overhauling it.

(Photo by Jim Vondruska/Getty Images)

Already, there are hints that a President Harris would be considerably more open-minded about the subject than her predecessor. As a presidential candidate in May 2019, Harris blamed Republicans for creating a “crisis of confidence” in the Court, and said that she was therefore “interested in” and “open to” the idea of adding justices to it. “We have to take this challenge head on, and everything is on the table to do that,” she told Politico around the same time.

As a senator from 2016 to 2020, Harris, like most Democratic senators from 2016 to 2020, was generally critical of Trump’s Supreme Court nominees. But unlike most Democratic senators, especially those of a certain age, her attacks often centered on the partisan behavior of the Republican justices, and on the importance of control of the Court to the conservative legal movement’s policy agenda. In 2019, for example, Harris called for the impeachment of Justice Brett Kavanaugh for lying during his confirmation hearings, arguing that his presence on the bench was an “insult to the pursuit of truth and justice.” And in 2020, she framed the rushed Barrett confirmation process as integral to right-wing attacks on the Affordable Care Act, and accused Republican senators of (once again) attempting to “bypass the will of the voters and have the Supreme Court do their dirty work.”

Even in the early days of her Senate career, Harris was notably attuned to the practical implications of the Court’s decisions. When announcing her opposition to the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch, she wrote that his rulings as an appeals court judge “repeatedly have failed to achieve justice for all Americans,” and “valued narrow legalisms over real lives.” She went on to predict that Gorsuch would vote to further erode labor rights (correct), empower corporations to deny access to birth control coverage (also correct), and make it difficult for federal agencies to do the day-to-day work of governing (perhaps the most correct of all).

As vice president, Harris has not really broken from Biden’s cautious approach to Supreme Court reform. But her rhetoric has been sharper: Since the Court overturned Roe in 2022, for example, Harris has repeatedly attacked it for robbing half the country of bodily autonomy, and explicitly blamed Roe’s death on Trump and the justices he appointed. By contrast, although Biden called the decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization a “mistake,” he did not use the word “abortion” in his most recent State of the Union address, which for a Democratic elected official in 2024 is borderline political malpractice.

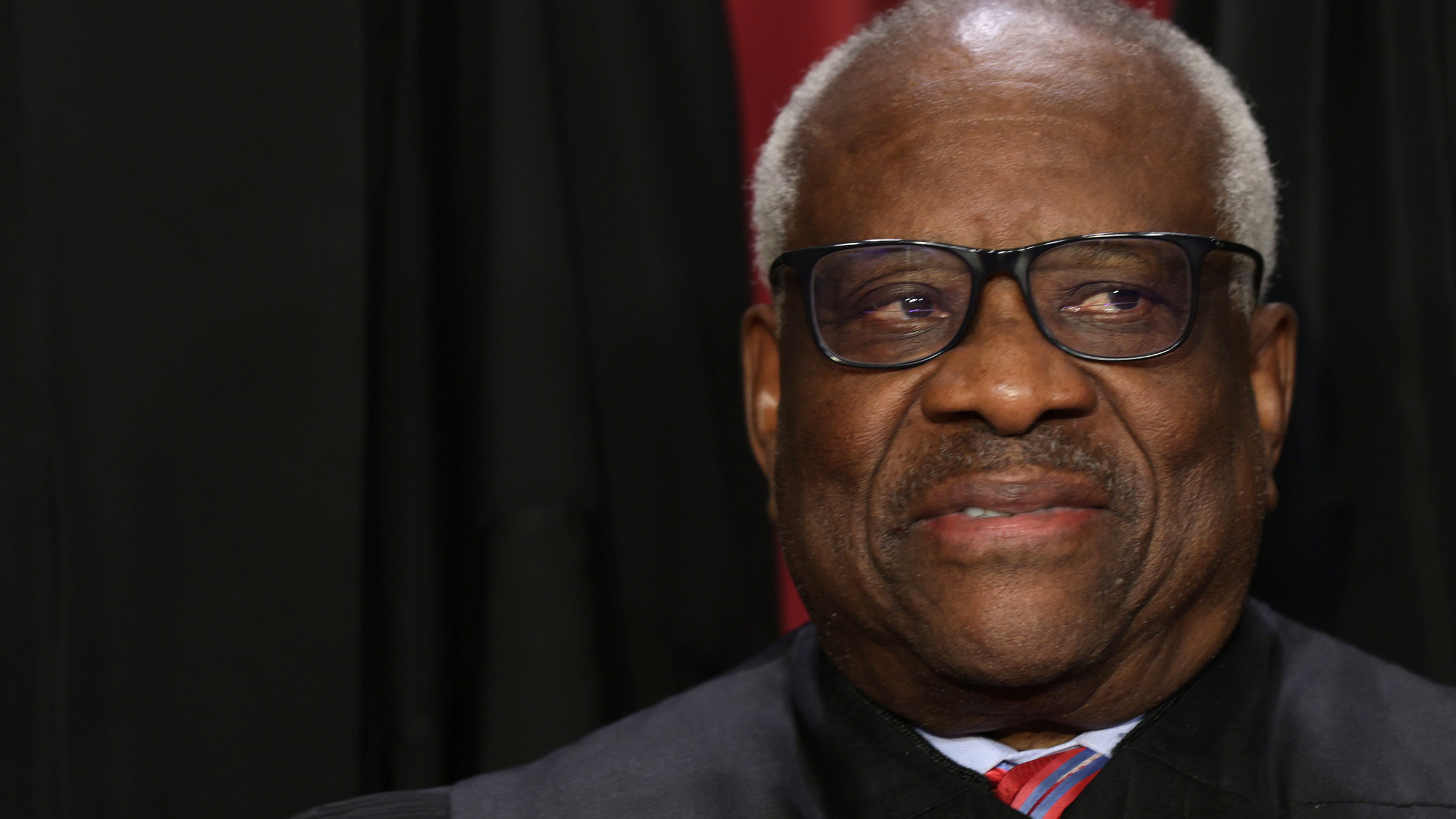

Maybe the most notable aspect of Harris’s treatment of the Court is the frequency with which she emphasizes that Dobbs, as bad as it was, is just the beginning of what the conservative justices hope to accomplish. She has highlighted Republican efforts to implement a nationwide abortion ban at their earliest opportunity, and predicted that a second Trump term would bring “more bans, more suffering, and less freedom.” Earlier this year, she warned that this “activist Court” posed a threat to “fundamental freedoms across the board,” pointing to Justice Clarence Thomas’s calls to eliminate rights to sexual privacy and contraceptive access as “some indication…[of] where they might go next.”

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

For all of Biden’s accomplishments when it comes to diversifying the federal bench, his Supreme Court reform efforts have been, to put it gently, disappointing. He opposed both term limits and Court expansion in the 2020 primary race, and did not revisit these positions even as the justices spent his White House tenure issuing decisions that did more for the Republican Party than most Republican elected officials could ever dream of. Before last week, Biden’s boldest response to a legal system captured by right-wing extremists was convening a Supreme Court reform commission that included zero proponents of Supreme Court expansion, which sent a pretty clear signal about the sorts of answers he hoped to get back.

But things are different now than they were four years ago, when Ruth Bader Ginsburg was alive, and presidents could still be prosecuted for committing crimes, and pregnant people weren’t getting airlifted out of red states in order to avoid bleeding to death. As recently as July 2020, 58 percent of Americans approved of the Court’s job performance. Even after Barrett’s confirmation, many liberals didn’t think the conservative justices would be so bold as to formally overturn Roe. Whatever their personal politics, the argument went, surely they would not toss five decades’ worth of precedent just because they had the power to do so.

No one—at least, no one who does not attend annual Federalist Society conclaves—believes this fairy tale anymore. The Court’s approval rating now sits at 38 percent, and public support for term limits (78 percent) and a binding ethics code (75 percent) tracks public support for ice cream and puppies. Enthusiasm for Supreme Court expansion isn’t at that level yet, but it’s higher than it’s been in recent years, and tends to spike every time the justices release a(nother) decision that reminds the public of how terrible they are. Normal people understand that the institution is broken, and want politicians who want to fix it before it takes away whatever civil rights are left.

Harris probably won’t answer every question about her Court reform agenda by Election Day 2024. But there is good reason to believe that she thinks of the Court’s Republican justices as all Democrats should think of the Court’s Republican justices: not as colleagues they have to persuade, but as opponents they have to defeat.