In the first few decades of the 21st century, American democracy hasn’t exactly thrived. The Supreme Court kicked off the new century with one of the most egregious decisions in its history, Bush v. Gore, in which five justices handed the presidency to a man who lost the popular vote, and may or may not have lost the Electoral College. Republican state legislatures have been systematically undermining voting rights, eroding even the semblance of a representative democracy. And in 2021, Donald Trump and his supporters led a coup attempt that led to multiple deaths and marked the first violent transition of power from one president to another in U.S. history.

But even as our relatively young democracy has declined, Americans have at least been able to hold onto the foundational notion, as old as the country itself, that in the United States, no one—not even the president—is above the law. If not a thriving democracy, we could at least rely on the fact that we remained, as John Adams framed it, a nation of laws, not men.

Earlier this summer, the Supreme Court decided that in fact, we are a nation of one man—Donald Trump. In Trump v. United States, the far-right majority on the Court found that presidents have absolute immunity for all “official acts” under Article II of the Constitution (i.e., when they’re doing work the Constitution specifically assigns to the president, like commanding the military), and presumptive immunity for all official acts that fall outside of their Article II responsibilities (a term the Court did not define, so who knows what pro-Trump judges could decide this entails).

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent, the decision “reshapes the institution of the Presidency,” and “makes a mockery of the principle, foundational to our Constitution and system of Government, that no man is above the law.” The stakes of this decision can hardly be overstated. After Trump, for example, it is no longer clear that a president could be prosecuted for ordering SEAL Team Six to assassinate a political rival. The decision poses an existential threat to the work of building back and maintaining a functioning democracy.

Fortunately—and, honestly, somewhat surprisingly—Democratic politicians have responded forcefully to the ruling. Shortly after the decision was published in July, President Joe Biden called for a constitutional amendment, the No One Is Above the Law Amendment, which would overrule Trump and re-establish that former presidents are not immune from criminal prosecution.

Unfortunately, there is absolutely no reason to think we’ll be adding a 28th Amendment any time soon. The Constitution was last amended in 1992, and legal scholars argue that the U.S. Constitution is the hardest to amend of any in the world. The No One Is Above the Law Amendment is really a messaging tool—an important messaging tool, but not one that will actually undo the harm wrought by the Supreme Court this summer.

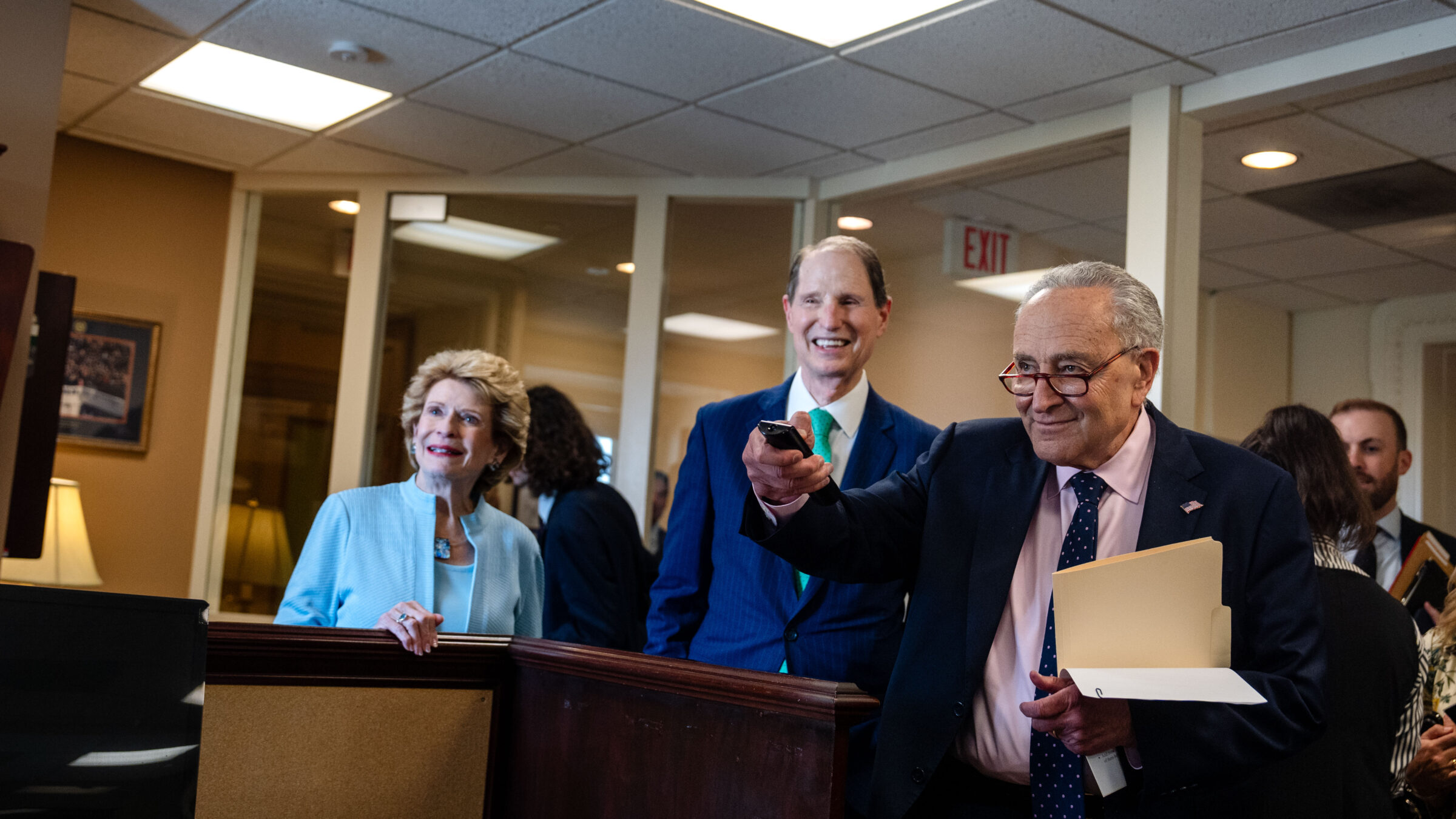

Recognizing the infeasibility of passing a constitutional amendment, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has proposed a different approach. On August 1, he led 34 Democratic senators in introducing the No Kings Act, which affirms that presidents have no immunity—absolute or presumptive—from criminal prosecution. It forcefully argues for an interpretation of the Constitution that recognizes that the president is bound by law just like anyone else. The No Kings Act is a direct attempt to use the standard legislative process to state unequivocally what the law is and what the Constitution means.

(Photo by Kent Nishimura/Getty Images)

Perhaps the most important part of the legislation stems from Senate Democrats’ awareness that the current Supreme Court disagrees with the assertion that the president is, in fact, bound by the law. So they’ve worked to ensure that the No Kings Act cannot be invalidated by John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh, Sam Alito, and their fellow pro-Trump justices, by stripping the Court of jurisdiction to hear constitutional challenges that arise from it. Questions regarding the act’s constitutionality instead go to a federal trial court in Washington, D.C., and on appeal to the D.C. Circuit. Notably, both of these courts heard Trump v. United States before it was appealed to the Supreme Court, and both found that the president is not entitled to any immunity from criminal prosecution. Further, the No Kings Act instructs courts to presume that the act is constitutional, unless it can be proven otherwise by “clear and convincing evidence.”

Biden and Schumer are both attempting to answer the same question: What can we, the people, do when the Supreme Court goes rogue, ignores the mandates of the Constitution, and destroys our democracy in the process?

One option is to engage on terms that accept judicial supremacy—the notion that the Supreme Court is the final word on what the Constitution means. This is, in essence, the Biden approach. Advocating for a constitutional amendment as the path forward implies that the Court got the Constitution right in Trump v. United States—or at least that ultimately, only the justices’ opinions about what the Constitution means matter—and so we need to fix the Constitution through the amendment process.

This approach at least makes clear that we can do something when the Court is so far out of line. But given the near impossibility of success, proposing it is a bit like bringing a pocket Constitution to a fight with Trump’s SEAL Team Six. It’s something, yes, but it’s probably not going to be enough to save you.

The alternative is the Schumer approach: affirming every co-equal branch of the federal government’s obligation to interpret the Constitution for itself. This is known as departmentalism: the theory that each branch has equal authority to interpret the Constitution insofar as it guides that branch’s actions. Because Congress is constitutionally tasked with determining to whom criminal laws apply, this argument goes, Congress is entitled to interpret the Constitution as it relates to that authority, without forced deference to the Supreme Court. So, when there is a conflict between the branches’ interpretations of questions of presidential immunity, the legislature is not obligated to throw its hands up in deference to the judiciary, but can instead provide its own interpretation of the Constitution, as it does in the No Kings Act.

Through this act of constitutional interpretation, 34 Senate Democrats are making their case that the Constitution does not immunize the president from prosecution. And by passing the No Kings Act, the people (through their elected representatives) could put both the Court and the president in their proper places in our democratic order by saying that the Court got the question of immunity wrong, and that’s that—the Supreme Court is out of control and cannot be trusted on this matter, so they lose their right to weigh in at all.

This idea—that the courts generally, or the Supreme Court specifically, need not have the final word on what the Constitution means—is far from new. But only in the last 50-odd years, ever since the liberal embrace of judicial power during the Warren Court era, has judicial supremacy become so broadly accepted as to now go largely unquestioned. Through the No Kings Act, Democratic Senators are showing that the Supreme Court is neither uniquely capable of, nor exclusively tasked with, interpreting the constitution. In that way, the No Kings Act does not just say that the president is no king. It says that Supreme Court Justices are not kings, either.