Earlier this year, the Supreme Court’s six conservative justices issued a sweeping ruling that blesses presidents, including Donald Trump, with immunity from prosecution for crimes they commit while in office. In response, Senate Democrats introduced the No Kings Act, which would abolish this immunity doctrine and strip the Court that created it of the power to hear challenges to the law’s constitutionality. Such cases would instead go to a federal district court in Washington, D.C., and then on appeal to the D.C. Circuit, thus keeping the authoritarian-curious parts of Sam Alito’s brain from doing any more damage to American democracy than they’ve already done.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about this proposed intervention, even among the immunity decision’s (many) critics. In a column published last week, for example, The Washington Post’s Ruth Marcus calls the decision a “travesty,” but argues that Democrats would be unwise to embrace the “situational ethics” of the No Kings Act. If they limit the Court’s authority to hear cases in this context, she says, future Republican legislatures might limit the Court’s authority in contexts that Democrats will not like—for example, by passing a “No Gay Marriage Act” with a jurisdiction-stripping clause that overrules Obergefell v. Hodges by legislative fiat.

Weighed against other Court reform proposals, Marcus frames the No Kings Act as better than “even more unwise alternatives, such as expanding the size of the court,” and notes that it would have an impact on the Court’s work more quickly than term limits. But for her, these advantages are not enough to move the needle. “Must liberals unilaterally disarm in the face of a court that aggressively disregards precedent and misreads the Constitution?” she asks, in what is somehow not a rhetorical question. “This is frustrating, but the better answer is yes.”

Undoing the damage this Court has wrought will take “time, as well as Democratic electoral victories,” Marcus concludes. In the meantime, she urges “patience and restraint.”

It might be true that Republicans would treat the No Kings Act’s extremely-hypothetical passage as a license to try and remove other subjects from the justices’ purview. But however you feel about the merits of this argument for (even more) liberal inaction on Supreme Court reform, the proffered alternative—waiting on Democrats to win more elections—is not a plan for reforming the Supreme Court. It is an unfounded expectation that everything will work out as you believe it should. For Democrats, this has not been a well-placed bet of late, as the justice whom President Hillary Clinton nominated to replace Antonin Scalia can attest.

“Time,” moreover, is not a luxury afforded to the millions of people whose lives this Court’s decisions are actively making worse, and a desire to ward off the abstract possibility of undesirable consequences is a poor excuse for abandoning those people indefinitely. Passing on a chance to limit your political opponents’ power does not guarantee that they will someday reciprocate such a sporting gesture. It only guarantees that you will have squandered an opportunity to limit your political opponents’ power, which you may or may not get again.

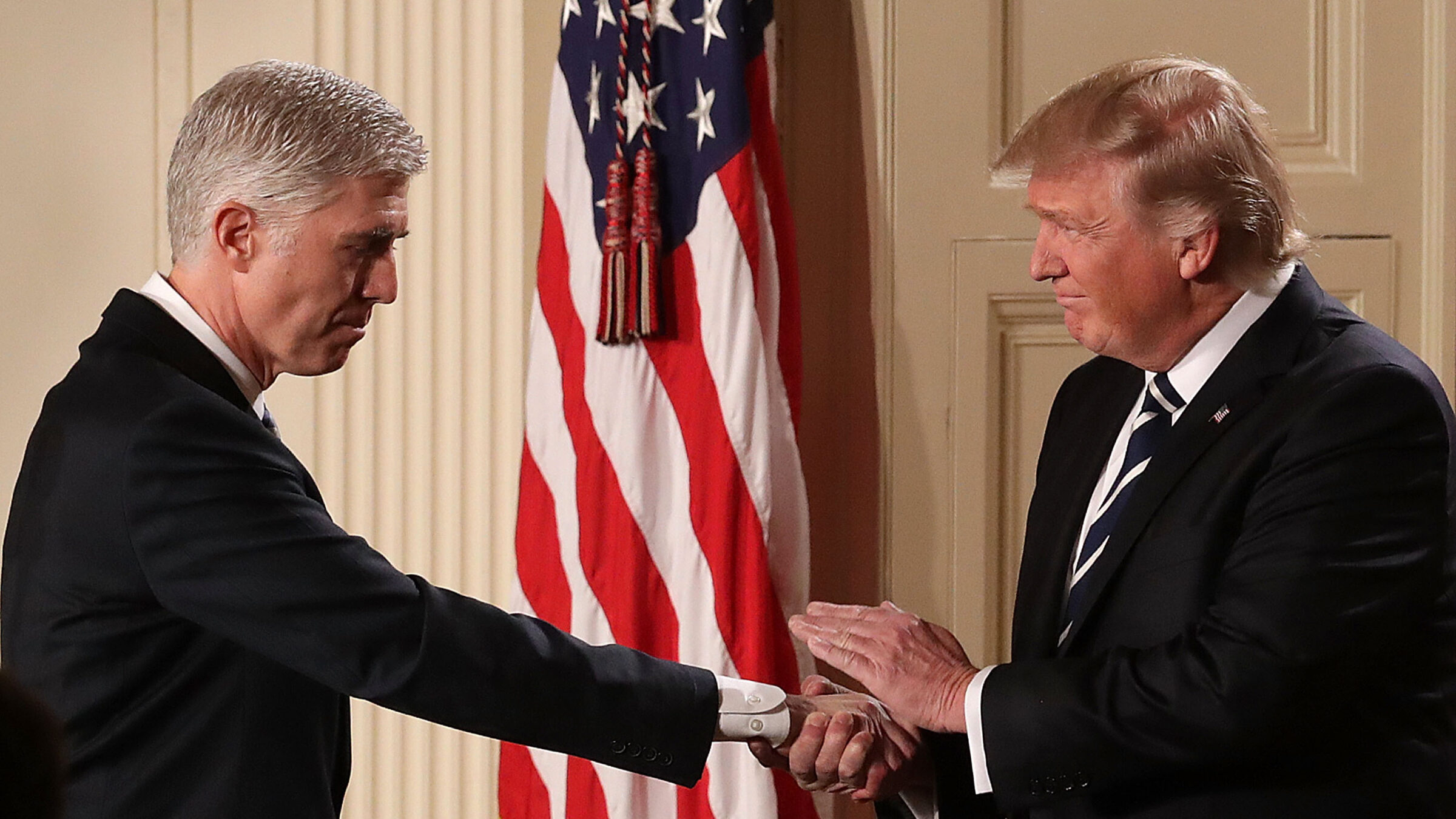

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Democratic outcomes do not correlate well with control of the Court, which instead hinges mostly on how close to an election an octogenarian lawyer happens to die. This is why Trump, who lost the popular vote but narrowly won the Electoral College in 2016, got to appoint three justices in four years, which is as many as Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden appointed in twelve years combined. And as the Court has grown more conservative, it has also grown more savvy about protecting its power, deciding a blizzard of cases that will make it harder for Democrats to win elections. Similarly, the prospect of another four-year Trump presidency is even more alarming today than it was a year ago, now that he understands precisely how unconcerned the justices he appointed are with holding him accountable.

Even if future Democratic candidates are as successful as they hope—and even if future vacancies break a little more in their favor—the substance of the Court’s work can be as relevant to its ideological balance as the process by which its justices take office. The longer that Democrats meet the Court’s unapologetic extremism with reflexive supplication, the more difficult it will be to eventually undo the justices’ most pernicious handiwork.

Even commentators who are theoretically more open to Court reform can get skittish when it comes time to follow through. Last month, after Biden announced his support for (among other things) a constitutional amendment to undo the Trump immunity decision, Berkeley Law professor Erwin Chemerinsky warned excited Democrats to pump the brakes. “Those reforms are unquestionably desirable but they have little chance of being enacted,” he wrote in The New York Times. “The laser focus for Democrats and others alarmed by the direction of the court should instead be on the November election.”

Again: What, exactly, is Erwin Chemerinsky waiting for? Polling from earlier this month found that 76 percent of voters agree that the justices should be subject to a binding ethics code, and 70 percent (including 54 percent of Republicans!) believe that winning the White House should not come with an irrevocable license to do crimes. Fully 70 percent of Democrats say the Court is a “very important” issue in deciding how they’ll vote this fall, compared to less than half of Republicans and independents. Voters who have spent the last several Junes watching the justice grind a fresh set of civil rights underfoot are understandably interested in hearing from candidates who will (finally) take their checks-and-balances responsibilities seriously.

Chemerinsky’s position seems to be that Democrats should not be wasting their breath pushing long-shot legislation when they have a generationally important election to win. But even if Biden does not literally sign a term limits bill before January 20, 2025, pushing for Supreme Court reform could very well make it easier for Democrats to win in November, by mobilizing the millions of energized voters—Democrats and otherwise—who are weary of the Court’s right-wing supervillain act. There is zero political cost to running against a historically unpopular Court, and if anything, Democrats should be talking about it more, not less.

Democrats have previously paid a high price for their reluctance to act in this space. After the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett in 2020, many politicians who opposed Court reform cited ominous-sounding concerns about Republican retaliation down the road. This includes Biden, who openly opposed term limits and said he was “not a fan” of Court expansion, which, he predicted in 2019, would “come back to bite us” after Republicans responded in kind. For voters who were angry at and/or afraid of the Court, voting blue no matter who was the solution; asking blue politicians to use power to do something about the Court was not.

Even after Democrats won the House, Senate, and White House in 2020, conventional wisdom did not change: Biden’s commission on Court reform recommended against expansion, warning that it would cause the public to “see the Court as a ‘political football.’” Three years and no additional seats later, Roe is dead, affirmative action is on life support, millions of middle-class borrowers remain mired in student debt, and Trump might never have to answer for his efforts to overthrow his own government. Not coincidentally, just 43 percent of Americans approve of the Court’s job performance, and 57 percent, including 55 percent of independents, believe its decisions are motivated “mainly by politics.” As it turns out, it wasn’t Court expansion that caused people to clock the justices as partisan hacks; it was the ensuing tidal wave of reactionary jurisprudence that Democrats did nothing to stop.

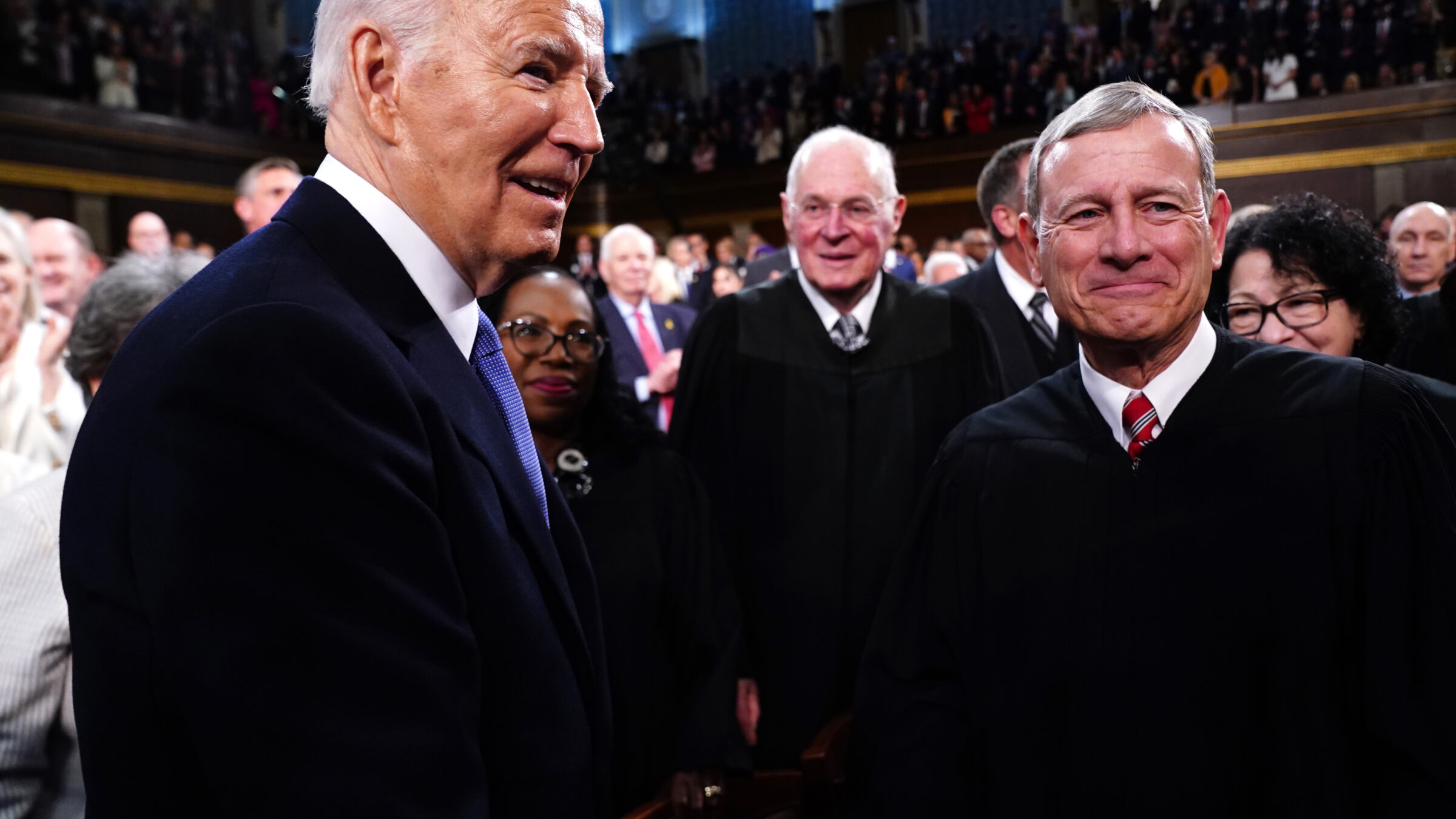

(Photo by Shawn Thew-Pool/Getty Images)

This is moot now, of course; as Marcus and Chemerinsky note, no Court reform bill is going to pass while Republicans control the House, and we are three months away from an election that will scramble the legislative landscape all over again. But this does not mean that the No Kings Act is unwise, or that Democrats should not be talking about it on the campaign trail. The party establishment has spent years approaching the Court in a preemptive defensive crouch, forevermore waiting for some (vaguely-defined) set of circumstances in which they’ll feel (maybe marginally more) comfortable backing reforms that their voters are now clamoring for. Again, a quick glance at the scoreboard indicates that this gameplan has not worked out.

If you are a politician who believes the Supreme Court is an out-of-control disaster—not at some point in the future, but right now, as you read this sentence—you have an obligation to use the power voters have entrusted to you to bring the justices to heel, or at least to try. Those who defend an unelected Court’s repudiation of the elected legislature as inherently legitimate, but who would treat the elected legislature’s repudiation of an unelected Court as beyond the pale, are not upholding a system of co-equal branches of government. They are willfully placing the least accountable branch above everyone else.