When Republicans blocked then-President Obama from replacing the late Justice Antonin Scalia, leaving his Supreme Court seat vacant for over a year until after the presidential election that followed, calls for Supreme Court reform began to simmer. Five years later, as a radical right-wing Court prepares to strip half the country of bodily autonomy, those progressive demands to fix the judiciary are boiling over.

Many reform advocates argue that Court reform is necessary because conservative elites have hijacked the Court by flouting norms and laws alike. They’re right, but that’s not the only or even the best reason to expand the Court. No disrespect to Merrick Garland, but I am not particularly energized by already-powerful white men’s employment prospects, or exacting revenge on their behalf.

I care immensely, however, about representative government. And most of America has never been represented by the Supreme Court. For almost all of this country’s history, the rules that govern the lives of millions of people—people of all races, genders, incomes, religions or lack thereof, and more—have been determined by a select, tiny handful of old white men who went to Ivy League schools. The country is larger and more diverse than ever, but the Supreme Court has largely remained stagnant. Expanding the Court would represent an expansion of democracy itself.

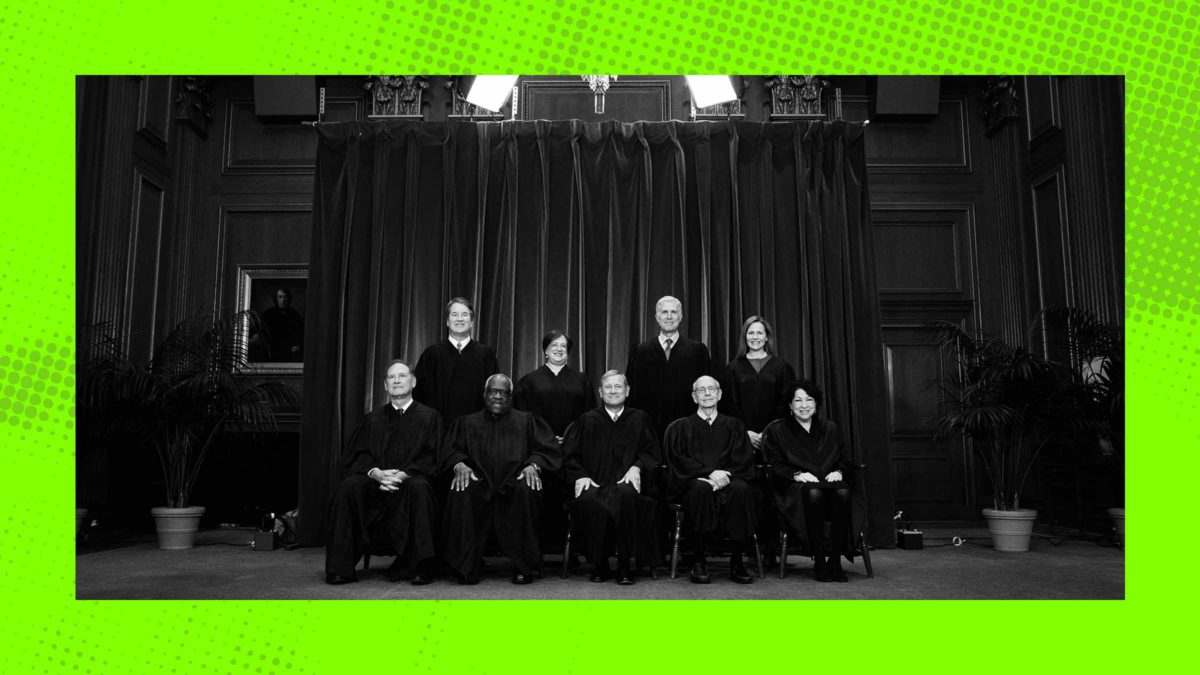

The Court’s historical composition shows a commitment to homogeneity above all else. I did some rough math: Of the 115 justices, 93.9 percent have been white men. Every chief justice has been a white man. There has never been an openly LGBTQ justice. Or an Asian American. Or a Muslim. As for the current bench, all but one justice are alums of either Harvard Law or Yale Law School; until Justice Amy Coney Barrett stole her seat, it had been nearly fifty years since anyone became a Supreme Court justice without passing through Harvard, Yale, or Stanford law schools first. Many justices were previously lawyers representing large corporations; none since Justice Thurgood Marshall, who retired in 1991, have had meaningful criminal defense experience. And, damningly, there are fewer women of color on the Supreme Court than men credibly accused of sexual misconduct. Large segments of the country are always the judged, never the judge.

(Photo by Mathew B. Brady/Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

This is not to say that representation is everything, or that only people of a particular demographic will decide particular legal disputes in a uniform way. Marginalized peoples are obviously not a hivemind. (There’s basically nothing I have in common with Clarence Thomas, for instance, beyond oxygen consumption, melanin, and a law degree.) But it is also true that an extreme minority of the country has always made up an overwhelming majority of the Supreme Court, and this built-in bias is reflected in their rulings. Rich old white guys are overrepresented on the Court; white and wealthy interests are overrepresented in the Court’s decisions. It’s easy to connect the dots. Adding justices to the Court would not amount to representation for representation’s sake, but would protect everyone’s rights while also introducing new considerations that have been purposefully excluded.

Legal scholars have long found that a more diverse judiciary expands both the perception and reality of fairness in the legal system’s outcomes, thus fostering higher levels of public trust. This impression is important: More so than other government institutions, courts have only their reputations to rely on for their legitimacy. There’s no reason to accept the Supreme Court’s rulings as legitimate if the Court—part of a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people”—only serves a minuscule fraction of the country. Minority rule is basically the shark from Jaws, and we’re gonna need a bigger bench.

There are fewer women of color on the Supreme Court than men credibly accused of sexual misconduct.

Nine isn’t some magic number with intrinsic value, either. Congress has changed the size of the Supreme Court several times before—most recently by shrinking it to eight for over a year after Scalia’s death—and our Supreme Court is unusually small compared to many constitutional courts abroad. The United States’ population is over fifty times the size of Denmark’s, for example, but our highest court is half the size of theirs. Germany is a quarter of our size, and their constitutional court is almost double the size of ours. The U.S. is out of step with the global community, and Court expansion would be one way to catch up.

The Court’s size is also an outlier domestically, as court expansion is becoming increasingly common at the state level. Lately, these efforts have been championed by Republicans working to put the whole force of government behind changing who votes, who counts the votes, and who decides which votes get counted. But changing a court’s composition is not inherently nefarious; court reform can expand, rather than constrain, communities’ power to decide their futures. Earlier this year, Virginia added eight judges to its Court of Appeals, instantly quadrupling the number of Black judges and doubling the number of women. To President Biden and members of Congress: This could be us, but you playing.

Court expansion alone won’t repair the broken judiciary—“Fix the courts with this one weird trick! Republicans HATE this!”— but it will democratize our fragile political system. Frankly, that’s reason enough to do it: An expanded nation needs an expanded Court.