The federal judiciary is out of control. Far-right judges have decided they are above the law, using their lifetime positions not to advance the well-being of the country, but to increase their personal wealth and push their own ideological agendas. By doing nothing to stop the judiciary’s accumulation of power—both for the institution and the individual judges and justices who comprise it—Congress has given corrupt, extremist judges free reign to abuse positions of public trust for whatever ends they choose.

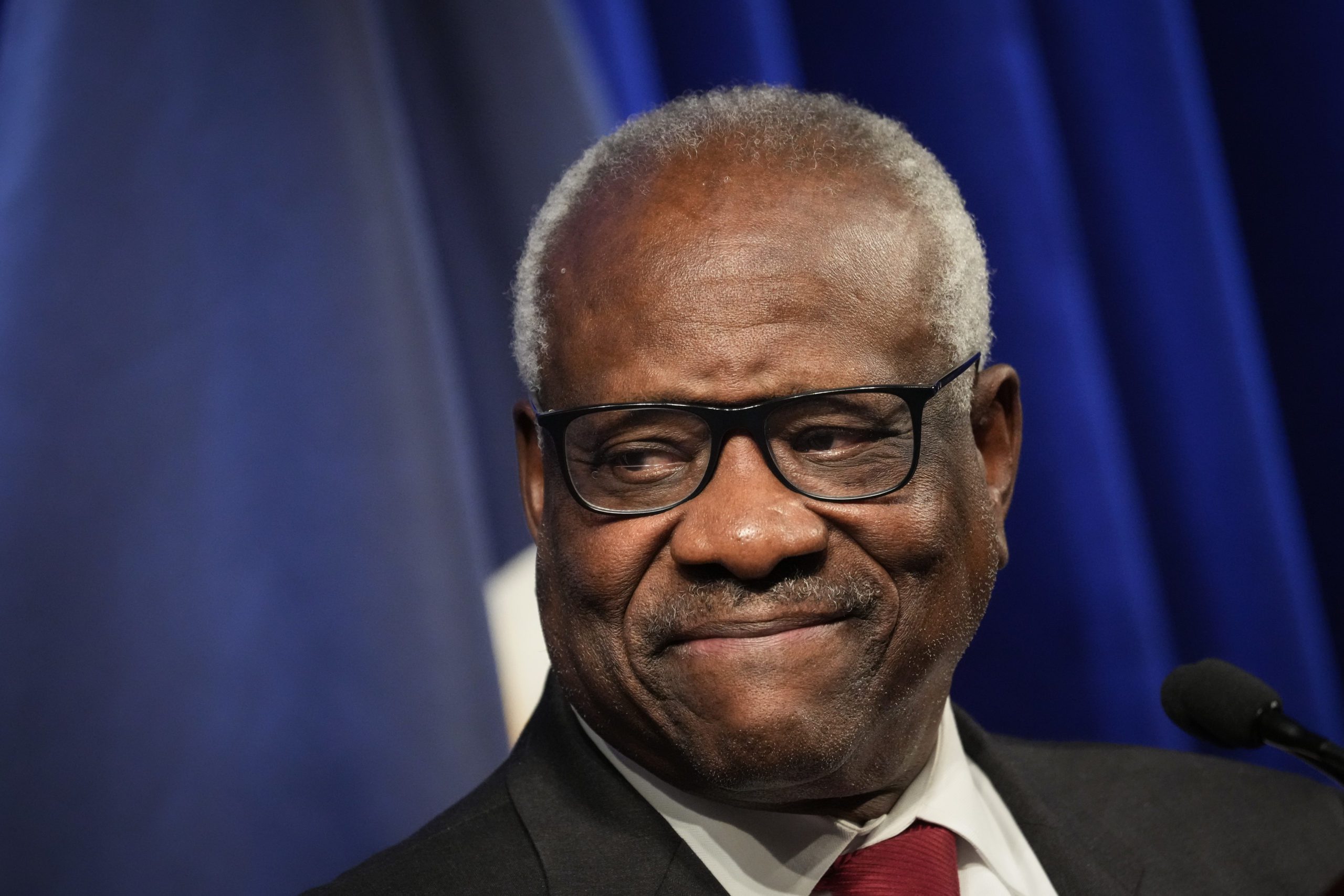

In early April, news broke that Justice Clarence Thomas has spent decades taking advantage of his “friendship” with Republican megadonor Harlan Crow, enjoying private jet flights, superyacht cruises, and half-million-dollar vacations that Crow was happy to fund. Crow, who went so far as to pay for a bronze statue of Thomas’s eighth-grade teacher, also purchased real estate directly from Thomas and his family. Thomas’s failures to disclose these gifts were “blatant violations” of federal law, according to legal experts.

Thomas claimed that unnamed “colleagues and others in the judiciary” advised him that he was not required to disclose the gifts because Crow did not have business before the Court. But last week, Zoe Tillman of Bloomberg reported that on at least one occasion, a company with ties to Crow did, in fact, have business before the Court, and Thomas failed to recuse himself—in the process, helping to shield a company in which Crow and his family held a non-controlling interest from a $25 million lawsuit.

Thomas isn’t the only justice whose personal dealings with wealthy individuals have made headlines. On Tuesday, Heidi Przybyla of Politico revealed that Brian Duffy, an executive at the law firm Greenberg Traurig, had purchased Gorsuch’s vacation home, which Gorsuch had been attempting to sell for years, just nine days after Gorsuch was confirmed to the Court. Gorsuch did not name Duffy on his financial disclosures, and has failed to recuse himself from some two dozen cases in which Greenberg has been involved during his six years on the Court.

When the host brings out another tray of Kobe beef sliders (Photo by Christy Bowe/ImageCatcher News Service/Corbis via Getty Images)

Nor is the judiciary’s disdain for the law limited to Supreme Court justices. Last month, a Texas district court judge, Matthew Kacsmaryk, attempted to end access to the abortion drug mifepristone in an opinion that one commentator called “legally indefensible.” Kacsmaryk, a Trump appointee, has his own history of ethics issues: He’s hidden the source of his personal fortune, and allegedly failed to disclose that he wrote an anti-trans, anti-abortion law review article during his Senate confirmation process.

The Supreme Court has—for now—stopped Kacsmaryk’s decision from taking effect. But it marked the next phase in the far-right war on bodily autonomy, laying the groundwork for legal efforts to ban abortion nationwide. People who can get pregnant, their families, and the economy as a whole are paying the price.

The notion that giving too much power to the least democratic branch of government is harmful isn’t new. And despite what the reluctance of prominent liberals to criticize the judiciary might suggest, it hasn’t always been a particularly radical position, either. In 1820, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the notion of “judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [is] a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.” Abraham Lincoln echoed this sentiment few decades later, arguing that letting the Court serve as the country’s ultimate policymaker would mean that “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.”

These views, perhaps unsurprisingly, were not shared by members of the judiciary. In 1803, the Court held in Marbury v. Madison that federal courts held the power of judicial review, allowing them to strike down an act of Congress if a simple majority of justices (at the time, just four) believed it violated the Constitution. Judicial review is a power grab that appears nowhere in the Constitution. By acquiescing to this decision, politicians from the White House to Capitol Hill have accepted rule by juristocracy in which the most important matters of the day are decided by judges, rather than elected representatives of the people.

The United States is an outlier among other democracies in its embrace of judicial supremacy: As Brian Highsmith and Kathleen Thelen have written, “our strong form of judicial review reflects one choice among many available institutional arrangements—and a comparatively unusual one, at that.” As legal academics including Niko Bowie have made clear, allowing the Court to veto voting rights protections, campaign finance regulations, and legislative attempts to address racial discrimination has not worked out very well for marginalized people in this country.

Fortunately, it’s not too late to decide that in a democracy, policy should be set by the people and their representatives, not Federalist Society activists in robes. Congress can act to stop flagrant violations of ethics laws, reign in far-right extremist judges and justices, and restore decisionmaking authority to the democratically accountable branches of government.

Clockwise from top left: nine lawyers who need better rules to follow (Photo by Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

As a first step, Congress can and must enact ethics reform. The Supreme Court, unlike the lower courts, is not bound by a code of ethics. A simple act of Congress could change this, ensuring that the justices have to follow the same rules as every other federal judge. Congress also has the power to subpoena Thomas, investigate his alleged misconduct, and initiate impeachment proceedings. Failing to take these steps would make clear that Congress will continue to tolerate justices operating as royalty.

These steps alone, however, are not sufficient, because they do not address the deeply rooted problem of a judiciary with too much power. (The harm caused by Clarence Thomas hiding trips on private jets pales in comparison to the harm caused by antidemocratic actors making the final decisions about virtually every aspect of life in the United States.) Congress can respond by stripping the judiciary’s power to hear cases related to specific pieces of legislation, or by routing all challenges to a given statute to a court of its choosing. It can eliminate the power of a single judge, like Kacsmaryk, to issue nationwide injunctions, a power invented by judges but well within the authority of Congress to modify or eliminate. As the commentator Jamelle Bouie has written, “It is a crisis when the fundamental rights of hundreds of millions of Americans are functionally overturned by an unelected tribunal.” Congress has the power to fix it.

When it comes to the Supreme Court specifically, Congress could require a supermajority to strike down federal legislation. It could also create a mechanism for expedited legislative review of Supreme Court decisions about statutes, allowing lawmakers to act quickly when the Court interprets a duly enacted law incorrectly. The question isn’t whether these checks and balances are legal or legitimate; Congress has deployed many of them before. The question is whether Congress is willing to fight for the power it is entrusted to wield on behalf of the people.

An antidemocratic judiciary is an active threat to the fight for progress. Accepting its continued dominance is a choice. By choosing a different path, Congress can return power to the people, where it belongs.