In April 2017, while celebrating his confirmation to the Supreme Court just nine days earlier, Neil Gorsuch got even more good news: At long last, someone decided to buy the remote lodge on the Colorado River that he’d put up for sale two years earlier. Gorsuch, along with two friends with whom he’d owned the property, had originally listed it for nearly $2.5 million, but even so, the $1.825 million sale price was nothing to sneeze at. Nor was the six-figure payout Gorsuch took home after the transaction closed a month later.

As it turns out, the deal’s timing and/or the buyer’s identity may or may not have been a coincidence. Per Politico’s Heidi Przybyla, the lodge’s new owner is one Brian Duffy, CEO of Greenberg Traurig, a corporate law behemoth with a bustling Supreme Court practice. Among roughly two dozen cases they’ve worked on since Gorsuch’s confirmation, Greenberg lawyers were prominently involved in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, a June 2022 decision in which the Court used a challenge to an Obama-era emissions rule to create for itself an absolute veto power over future executive actions it doesn’t like. Gorsuch, who has long despised both the administrative state in general and also EPA in particular, joined the other conservatives in voting for Greenberg’s client.

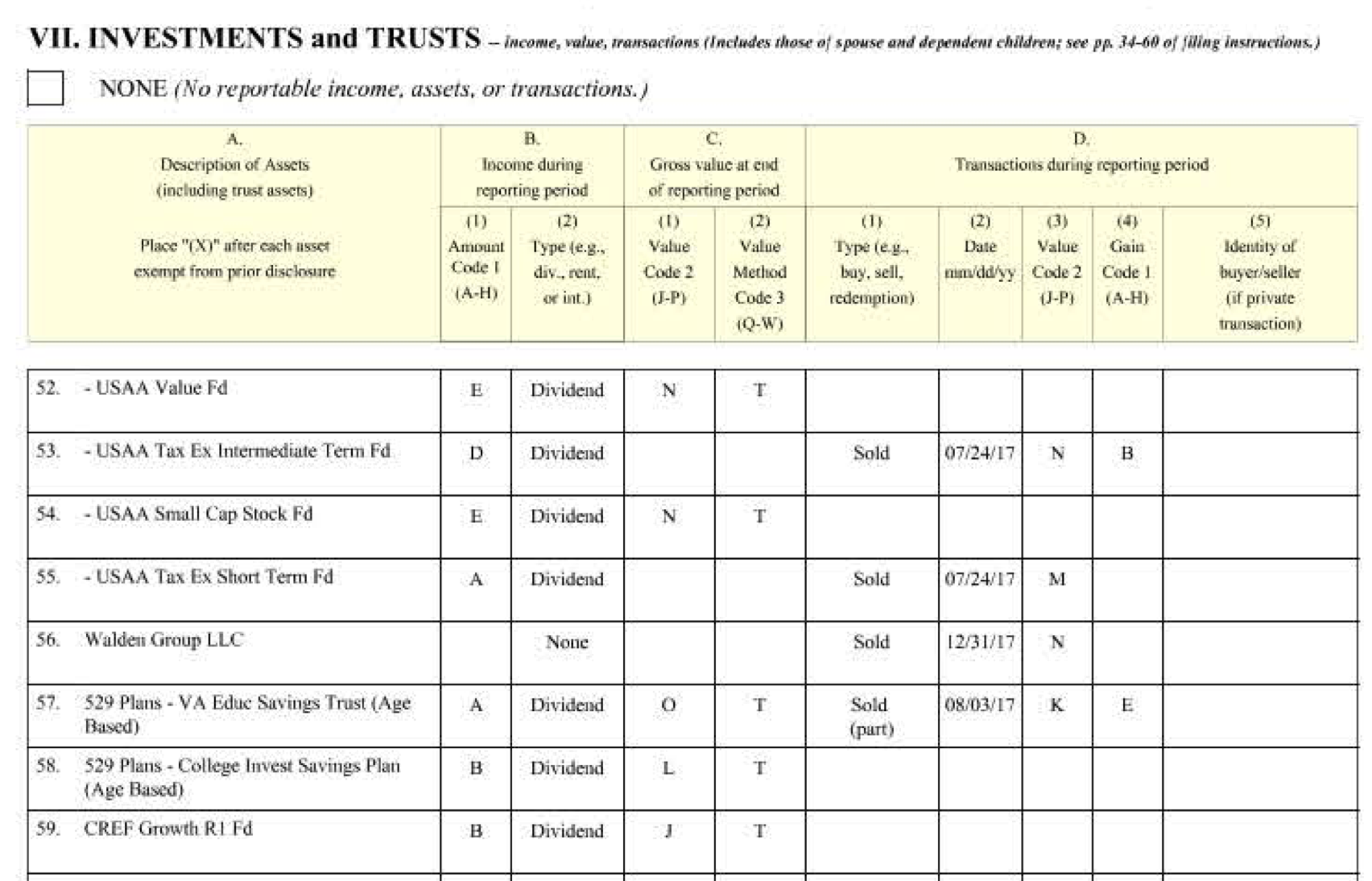

Federal law requires Supreme Court justices to file annual financial disclosures that are supposed to identify potential conflicts of interest—such as, for example, a BigLaw CEO turning up out of nowhere to buy a vacation home that had languished on the market for years, making the newly-minted Justice Gorsuch a few hundred thousand dollars richer in the process. But Duffy’s name appears nowhere in Gorsuch’s 2017 filings, which note the transaction way down on line 56 of Section VII, and only as the sale of the justice’s interest in “Walden Group LLC.”

Gorsuch’s defenders, a group that consists mostly of conservative law professors and, notably, other BigLaw attorneys, have a jargon-laden explanation ready for why this is Nothing To Be Concerned About. Gorsuch and his friends owned the property through a limited liability company, the Walden Group. Therefore, technically, Gorsuch did not sell the home, but instead sold his stake in the LLC that owned the home and sold it to Duffy. This, they argue, is why Duffy’s name would not and should not appear as the “buyer” on Gorsuch’s disclosures—legally speaking, Gorsuch did not actually sell anyone anything. (I will note here that one reason people buy property in the name of an LLC is a desire, for whatever reason, to mask the identities of the real parties in interest.)

Duffy, for his part, told Politico that he’s never even spoken with Gorsuch, let alone argued a case before him, and didn’t know Gorsuch owned the home when he made the offer. Duffy also says he consulted with the firm’s ethics department after learning that his most recent real estate acquisition enriched an honest-to-God Supreme Court justice.

The question of whether Gorsuch’s strategic use of Colorado corporate law complies with the intricacies of federal ethics and disclosure law is classic lawyer shit, in that it provides argumentative people with the chance to spend hours parsing ambiguous language before arriving at conclusions about which they feel very strongly. It also obfuscates the fundamental problem here, which is that the American legal system allows very wealthy people a multitude of options for buying access to Supreme Court justices. On the rare occasion that details become public, it happens only years later, maybe, if a journalist with time and resources and a working knowledge of the Colorado Secretary of State’s website knows where to look.

When that escrow money hits your checking account (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

I don’t know if Neil Gorsuch is taking six-figure bribes funneled through oddly-timed real estate buys in remote Colorado mountain towns. But you do not have to reach this conclusion to understand that a “disclosure” regime that disguises a BigLaw partner’s purchase of a $2 million vacation home from a life-tenured federal judge is not worth the paper on which it’s written. Even if Gorsuch followed the law here, and even if—I am being uncharacteristically gracious, but stay with me—this transaction was as innocent as the parties insist, this does not vindicate the existing rules, which the Supreme Court has long insisted are sufficient to address any lingering questions about whether its members are on the up-and-up. It exposes how hilariously inadequate the Court’s rules are for the task of keeping justices from flailing around inside billionaire cash cubes whenever they feel like it.

Maybe the most alarming aspect of the Gorsuch story, particularly in the context of Clarence Thomas’s annual superyacht jaunts on a Republican megadonor’s dime, is how easily a motivated rich guy with a savvy lawyer could bribe a justice, were they so inclined. If the name of an anodyne-sounding LLC is all it takes to polish the grimy details of who is paying who, and for what, and how much, this feels to me like a matter of when, not if. (Assuming it hasn’t happened already.)

The assumption underlying any disclosure regime mirrors the assumption underlying the entire legal system, which is that applying the same rules to everyone will inexorably yield fair and righteous results. This Supreme Court, and more specifically its broken fire hydrant of humiliating ethics scandals, reveals the hollow nature of this premise. Whether you blame Gorsuch for hiding the ball or the rules for allowing him to do so, the upshot is the same: No one can say with confidence that the Court is doing justice for anyone other than those who can afford it. Like the legal system of which they are a part, the rules provide only the illusion of fairness, while protecting the people who know how to take advantage of it.