Last year, the Supreme Court decided in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen that the Second Amendment prohibits gun regulations that are not “rooted in the Second Amendment’s text, as informed by history.” In English: Your elected representatives are no longer allowed to justify a gun regulation by arguing that the regulation is “reasonable,” or “isn’t taking anyone’s guns away,” or “saves lives.” Instead, they must argue that it’s the same kind of law that Congress would have passed when the Second Amendment was ratified.

For those keeping score at home, that was in 1791, before the invention of modern bullets, much less modern guns. Nevertheless, to adopt a rule to, say, keep guns out of polling places, the government must now “affirmatively prove” that its rule is “part of the historical tradition” of gun rights in this country.

But it’s going to be extremely difficult for governments to prove that regulations are part of any “historical tradition.” At the time the Second Amendment was passed, American society looked radically different. It’s not just that guns were more primitive. A huge section of the country had just served in militias to kick out the British. Far more people hunted for their food. Early governments needed armed men to suppress rebellions by indebted farmers or forcibly settle indigenous land.

As society changed, Americans had to settle new, different questions about the limits of gun ownership. And after Bruen, some of the reasonable answers that every state settled on are all at risk. Last month, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a longstanding federal statute that bars people with domestic violence-related restraining orders from owning guns. Back in 1791, those restraining orders didn’t even exist.

Radical right-wing federal judges won’t stop there. Also on the chopping block right now are rules to keep unsecured guns away from kids. In January, a three-judge panel of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals revived a case that could leave vulnerable kids in Illinois without any legal protection against finding a loaded gun on their kitchen table.

When someone asks if you ever think for more than three seconds about the possible consequences of your pseudointellectual judicial philosophy (Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)

Illinois, like many other states, has strict regulations for people who run daycares or take in foster children. Since 1969, Illinois has required its Department of Children and Family Services to set rules banning handguns from the homes of people who run daycares, unless someone who lives in the home needed a handgun for work. (In that case, the person must disassemble and lock their handgun and ammunition away from the children.) Plus, the daycare must inform customers that there is a gun inside and explain how they’re keeping the it away from the kids. Similarly, foster parents must lock all their firearms—not just handguns—to keep them away from the children they’re taking care of.

For anyone who wants to make sure their kid’s daycare doesn’t have a Glock in the sandpit, these are pretty reasonable rules. And they really shouldn’t be understood as restrictions on gun ownership as much as they’re rules to protect kids from the dangers that guns can present. In plenty of other contexts, courts recognize that a constitutional right can be relaxed to protect children from harm. The FCC regulates TV content more strictly during daytime. Children don’t always have to testify face-to-face against their alleged abusers. Lawmakers and courts have always recognized that as a practical matter, the 18th-century text of the Constitution sometimes has to bend to protect kids and vulnerable people.

But in 1791, Americans hadn’t invented foster care, or early childhood education, or state Departments of Children and Family Services. So there’s no historical tradition of rules to make sure that people fostering kids or watching other people’s kids don’t leave guns where the kids can get them. And that may be a problem for kids in Illinois soon. In 2018, gun rights groups filed a federal lawsuit arguing that Illinois’s rules were unconstitutional. In 2022, before the Bruen decision, Judge Sue Myerscough, an Obama appointee to a federal district court in Illinois, held that the rules were valid. Her opinion approvingly cited cases from other Illinois federal courts that upheld gun rules when the point of the rules was to protect children from accessing firearms—even when those rules put real restrictions on adults. “[T]he presence of children,” she wrote, “militates in favor of a given place” being a gun-free zone.

Before Bruen, the Seventh Circuit had held that rules that banned guns in certain places, like schools, didn’t infringe on an adult’s right to self-defense, because the adult could choose not to go into the school. Similarly, Myerscough found that because running a daycare is voluntary, the plaintiffs could regain their Second Amendment rights just by doing something else with their day. And Myerscough pointed out that the gun rights groups could only find one couple who claimed that they wanted to violate the state law. Apparently, none of the other daycare owners and foster parents in Illinois felt the need to turn every playdate into a thrilling, life-or-death adventure.

The state didn’t have peer-reviewed quantitative evidence to prove that the restrictions save lives. But Myerscough gave Illinois a pass on that. She pointed out that, because the rules had been in place since the 1960s, and many other states had similar rules, it would be difficult to show what would happen without the rules. (As a general matter, running social experiments that might result in deaths of children is frowned upon.) Essentially, Myerscough balanced the rights of daycare owners to leave unsecured guns around kids against the rights of kids to not be around unsecured guns, and she found in favor of the kids.

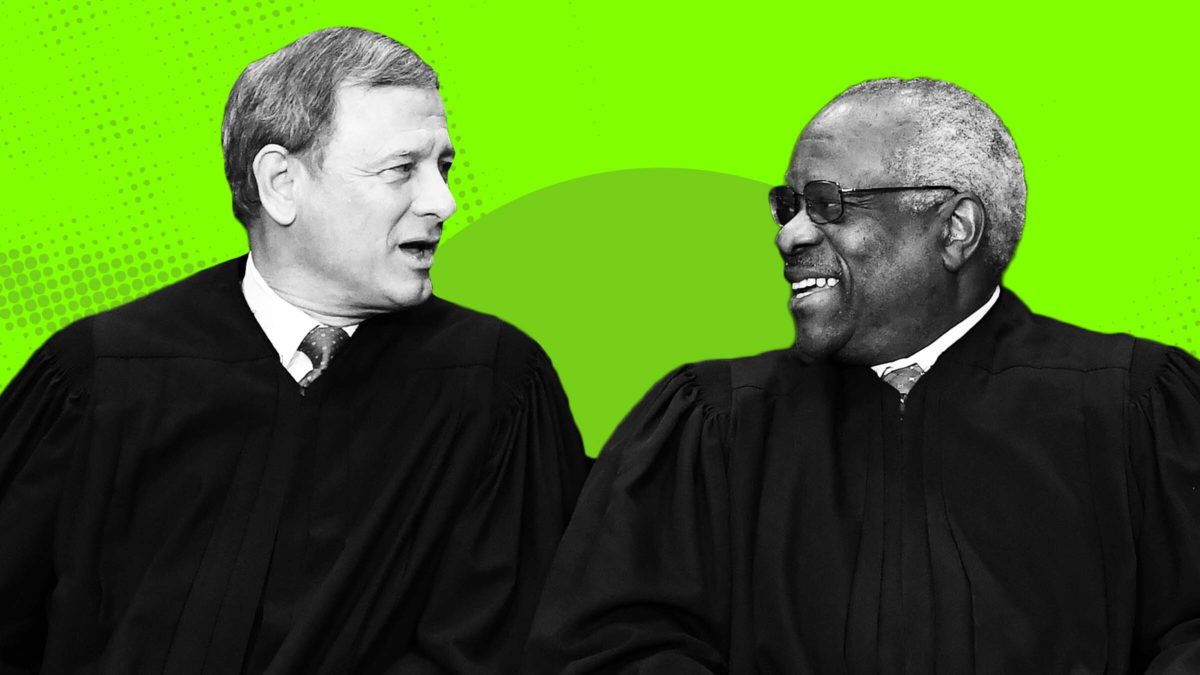

After the gun rights groups appealed Myerscough’s decision to the Seventh Circuit, however, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Bruen. And the balancing test that Myerscough used is exactly what Bruen prohibits: Justice Clarence Thomas, writing in Bruen, held that the Supreme Court’s prior cases “do not support applying means-ends scrutiny in the Second Amendment context.” The Second Amendment right to bear arms can’t be balanced against anyone else’s rights.

Accordingly, the Seventh Circuit panel—consisting of Reagan appointee Joel Flaum, H.W. Bush appointee Ilana Rovner, and Trump appointee Michael Brennan—sent the case back to Mysercough, ordering her to “allow the parties to engage in further discovery, including seeking additional expert reports.” That is, Illinois and the gun rights groups will have to find historians to report on whether there were any similar gun regulations in 1791 before Myerscough makes her decision.

When a parent asks if you care about helping to keep their kid safe (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Finding experts to testify about facts and exchange their reports is a normal part of many cases. But this isn’t a normal case. The Supreme Court has made its obsession with originalism into the test for whether a rule violates the Second Amendment. So when those historians give their opinion on “facts” about the kinds of rules the colonial-era states passed, they’ll really be opining on what the Constitution means.

The problem with the rigid “history and tradition” test Bruen imposes is that the law is not an objective fact that a historian can determine. Laws are rules. They’re subjective decisions made by political bodies like Congress, or your state legislature, or the Supreme Court. This isn’t a case that can be resolved by expert testimony about whether a car could have stopped in time to avoid an accident, or whether a family got cancer from a chemical plant contaminating their water supply. This is a case about whether Illinois should be allowed to keep kids safe from unsecured guns at daycares. The answer to that question can’t be divined from the Federalist Papers or the colony of New Hampshire’s statute books. You can’t discover whether guns should be allowed in daycares in a fucking laboratory.

Even if governments can find historians who are experts on the state of gun regulations in 1791, they still have to submit those opinions to judges, who then get to decide whether a gun rule is valid or not. However Myerscough decides this one, given the panel of three Republican judges that heard the first appeal in this case, it’s not hard to guess how it will end. And even if the Seventh Circuit listens to reason, Illinois will run headlong into a 6-3 right-wing supermajority on the Supreme Court.

The Court’s modern Second Amendment jurisprudence—first in District of Columbia v. Heller and then in Bruen—takes gun regulation out of the democratic process and placed it in the hands of unelected lawyers. Many of these lawyers have been training their whole lives to turn their unpopular agenda, which includes making America an open-carry zone, into unimpeachable, impervious constitutional law. Now that Bruen has made that dream a reality, the lower courts have free rein to overturn any gun law at all. That’s exactly what the Supreme Court wanted, and it’s exactly what every dead-eyed Trump appointee is going to do.