When a policy decision kicks off an avalanche of increasingly horrible, absurd outcomes, that’s the law of unintended consequences at work. But the consequences of the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, which made it near-impossible for lawmakers to meaningfully respond to America’s gun violence epidemic, were very much intended by the justices who made it. Now, lower courts are twisting themselves in knots, powerless to do anything other than throw out even the most modest of protections in the name of history and tradition.

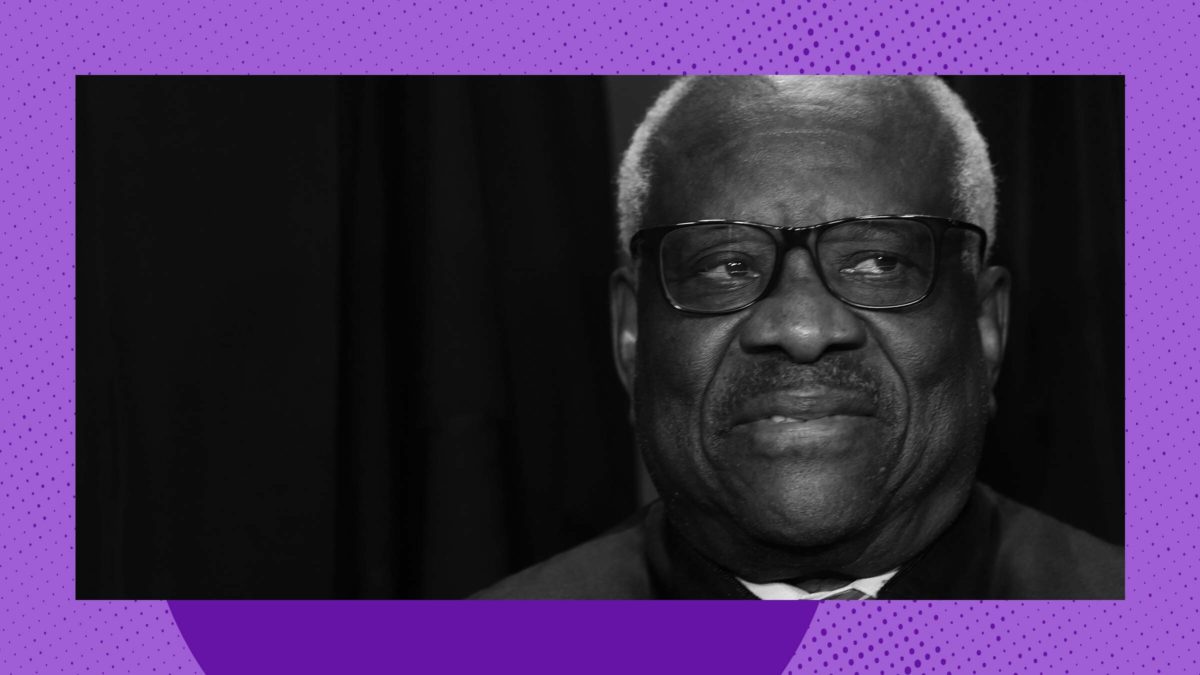

In Bruen, Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the six conservative justices, tossed a New York law that functionally required people to show a special need for self-protection to carry a gun in public. But that’s not the real story of Bruen, which was a vehicle for Thomas to come up with a new test for gun safety laws that is basically insurmountable: If a regulation is, in Thomas’s judgment, not “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation,” it’s out. For Thomas’s purposes, this “historical tradition” is whatever laws and firearms were in existence in 1791, when the Second Amendment was ratified.

Pegging the outer limits of policymaking in 2022 to whatever was happening a quarter-millennium ago is, to put it charitably, unhinged. Generally, making laws based on the whims of a small cohort of long-dead fancy white men is no way for a country to govern itself. This strategy is even more harmful when it comes to guns, which have come a long way since 1791, with many of the advances coming in the “much better at killing people” territory.

Before Bruen, courts were allowed to make common-sense judgment calls, like whether the state’s interest in limiting gun violence was sufficient to overcome the corresponding burden on Second Amendment rights. After Bruen, though, lower courts are stuck considering only what was happening centuries ago. There’s no longer any play in the joints to consider, for example, the increasing lethality of guns, the increasing density of the nation’s population, or the uniquely American enthusiasm for amassing dozens of weapons for fun.

When someone suggests that the government be able to do something about gun violence (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The first post-Bruen regulation to get tossed might be the most depressing. After ten people were murdered in a March 2021 mass shooting at a grocery store in Boulder, Colorado, several nearby municipalities, including Superior, passed laws restricting the purchase and sale of certain “illegal weapons,” including semiautomatic rifles with detachable magazines. The town provided ample evidence for the necessity of measures like these: These types of guns are commonly used for mass shootings and other violent crimes, and aren’t necessary for hunting or self-defense, and can be easily modified to make them even deadlier.

In July 2022, however, Judge Raymond Moore of the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado issued a temporary restraining order striking down the portion of the law prohibiting the sale of assault weapons. Moore said he was sympathetic to the town’s reasoning, but was “unaware of historical precedent that would permit a governmental entity to entirely ban a type of weapon that is commonly used by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes, whether in an individual’s home or in public.”

Notably, Moore’s order doesn’t require the gun owners who sued in federal court to prove what those “lawful purposes” might be. Instead, the court notes that “lawfully owned semiautomatic firearms using a magazine with the capacity of greater than 15 rounds number in the tens of millions,” as if the sheer numerical scope of ownership renders their perpetual ownership lawful.

“Home defense,” of course, looks much different today than it did In 1791, when muskets and flintlock pistols held a whopping one round at a time, such that “a skilled shooter could hope to get off three or possibly four rounds in a minute of firing,” per The Washington Post. A modern semiautomatic rifle pumps out 45 rounds per minute. The Framers could not have possibly divined that the country would get so good at manufacturing weapons like these. Yet thanks to Bruen, we have to accept as gospel that if you could keep a musket in your house 250 years ago, you can keep an assault rifle in your house as long as gun enthusiasts can come up with some tendentious explanation as to what a “lawful purpose” might be.

(On a grim little afternote, Moore later had to modify his order because Superior’s ordinance also prohibited the ownership of a “blackjack, gas gun, metallic knuckles, gravity knife, or switchblade knife,” none of which are implicated by Bruen. So, while the town can’t stop people from owning guns that shoot dozens of rounds per seconds, it can keep its residents safe from the scourge of brass knuckles.)

Two months later in Texas, Judge David Counts ruled that the government couldn’t enforce a 54-year-old federal law prohibiting people indicted for felonies from purchasing guns. In United State v. Quiroz, Jose Quinoz had lied about being under felony indictment when he filled out the necessary paperwork to buy a semiautomatic pistol. Quinoz’s application should have been flagged by the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, but thanks to a processing delay, the gun dealer went ahead and (legally) sold him the gun. Within a week, NICS correctly informed agents with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms & Explosives that Quinoz was under felony indictment, and he was arrested.

In his opinion throwing out the law, Counts admitted that “historical analogies from the 18th century would be difficult to find,” and that requiring the government to do so creates an “almost insurmountable hurdle. But Counts is stuck with Bruen, which he seems to understand yields a terrible result. “There are no illusions about this case’s real-world consequences—certainly valid public policy and safety concerns exist,” he writes. “Yet Bruen framed those concerns solely as a historical analysis. ”

Neither Moore nor Counts comes close to being as exasperated as West Virginia District Court Judge Joseph Goodwin, who recently had to throw up his hands and find unconstitutional a federal law that banned scratching serial numbers off guns. Serial numbers are used to trace guns used in crimes, but in 1791, there were no serial numbers, so now it doesn’t matter if you scratch them off. Goodwin’s frustration is palpable: “The usefulness of serial numbers in solving gun crimes makes [the law in question] desirable for our society,” he writes. But, he concludes, this is “the exact type of means-end reasoning the Supreme Court has forbidden me from considering.”

Indeed, Bruen’s originalist gibberish renders a good deal of legal analysis useless. Judges no longer need to do the hard work of reviewing precedent or weighing the possible harms that might flow from a decision. This sort of cramped reasoning isn’t just lazy—it is legal analysis for Luddites, a reflexively anti-progress worldview that freezes rights, responsibilities, and opportunities in an era that extended no grace to people of color, women, or LGBTQ individuals, among many others. But because more people owned a musket or two back in the day, we all have to live our lives with the incessant, grinding fear that comes with knowing that a gun could end them at any moment.