As horrifying new details emerge about the tragic school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, it is clear that police utterly failed in their jobs to protect the children and teachers of Robb Elementary School. Police remained remained outside a classroom for about an hour while the shooter continued his rampage. When a handful of frustrated parents tried to go save their children themselves, officers reportedly tackled them, pepper-sprayed them, and placed them in handcuffs.

These facts echo the tragedies in Parkland and the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, where police similarly failed to take action as shooters took dozens of lives. These failures are part of a pattern of incompetence by U.S. police, who kill about three people per day, solve about two percent of major crimes, and cause about a third of country’s wrongful convictions via police misconduct.

Despite the overwhelming evidence that police are terrible at their jobs, courts have made it nearly impossible to hold police accountable for these failures. Judges have stretched the concept of qualified immunity, which absolves officers from civil liability for their actions unless they violate a “clearly established” right, to limits that would be farcical if they were not causing such severe harm to real people. Judges have found that police cannot be held accountable for shooting people in the back, sending a police dog to attack someone who had already surrendered, and killing or injuring them with banned chokeholds, just to name a few.

In many cases, the Supreme Court’s decisions protect police from having to do their jobs at all. For anyone outraged that police in Uvalde sat outside as a heavily armed shooter murdered nineteen children and two teachers, look no further than cases like DeShaney v. Winnebago and Castle Rock v. Gonzales for part of the blame. In those cases, the Court decided that police—armed state agents who fancy themselves the “thin blue line” between peace and chaos—actually have no duty to protect the public from anything.

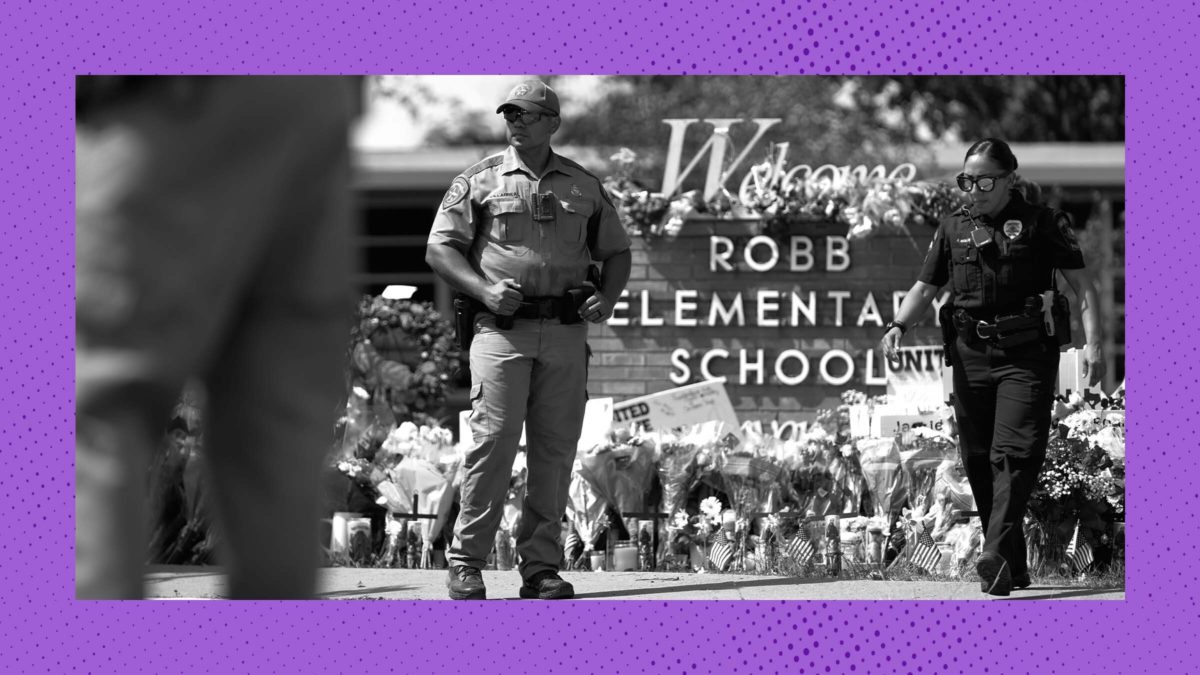

Texas Governor Greg Abbott, who praised the “amazing courage” of police in the shooting’s immediate aftermath (Photo by ALLISON DINNER/AFP via Getty Images)

In DeShaney, the Court sided with child protection agents who took no meaningful action despite knowing that a four-year-old boy had been repeatedly battered by his father. Eventually, the father put the boy in a coma. The Court’s assertion in the case, decided in 1988, was that government agencies do not have any special duty to protect residents from harms that they do not create themselves.

In Castle Rock, which the Court decided in 2005, police in Colorado took no action to find three missing girls who had been abducted by their father, despite frantic calls and visits to the police station from their mother and an active restraining order against the father. Sometime over the course of the ten hours that police ignored their mother’s pleas for help, the father murdered them. The Court held that even though a state law required police to enforce restraining orders, they could not be held accountable because of a supposed history of allowing police discretion in how they perform their jobs—discretion that apparently includes not performing their jobs at all.

Relying on this precedent, courts have excused police officers for egregious violations of their duty to “protect and serve.” Citing DeShaney and Castle Rock, they have ruled in favor of police who prevented a gunshot victim from receiving first aid, leading to his death; who watched without taking action as someone was stabbed repeatedly on the subway; and who released a drunk arrestee who was threatening to get her gun and shoot her boyfriend, and who indeed went on to kill him.

This would be bad enough on its own, but the Court’s conservatives are also about to realize their dream of eviscerating gun control in New York State Pistol & Rifle Association v. Bruen. Since the Court’s discovery of a private right to bear arms in District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008, gun deaths have increased significantly. In the face of soaring gun ownership and mass gun violence, the Court’s decisions relieving police of any duty to protect seem to make it more likely that we will be killed by police than saved by them.

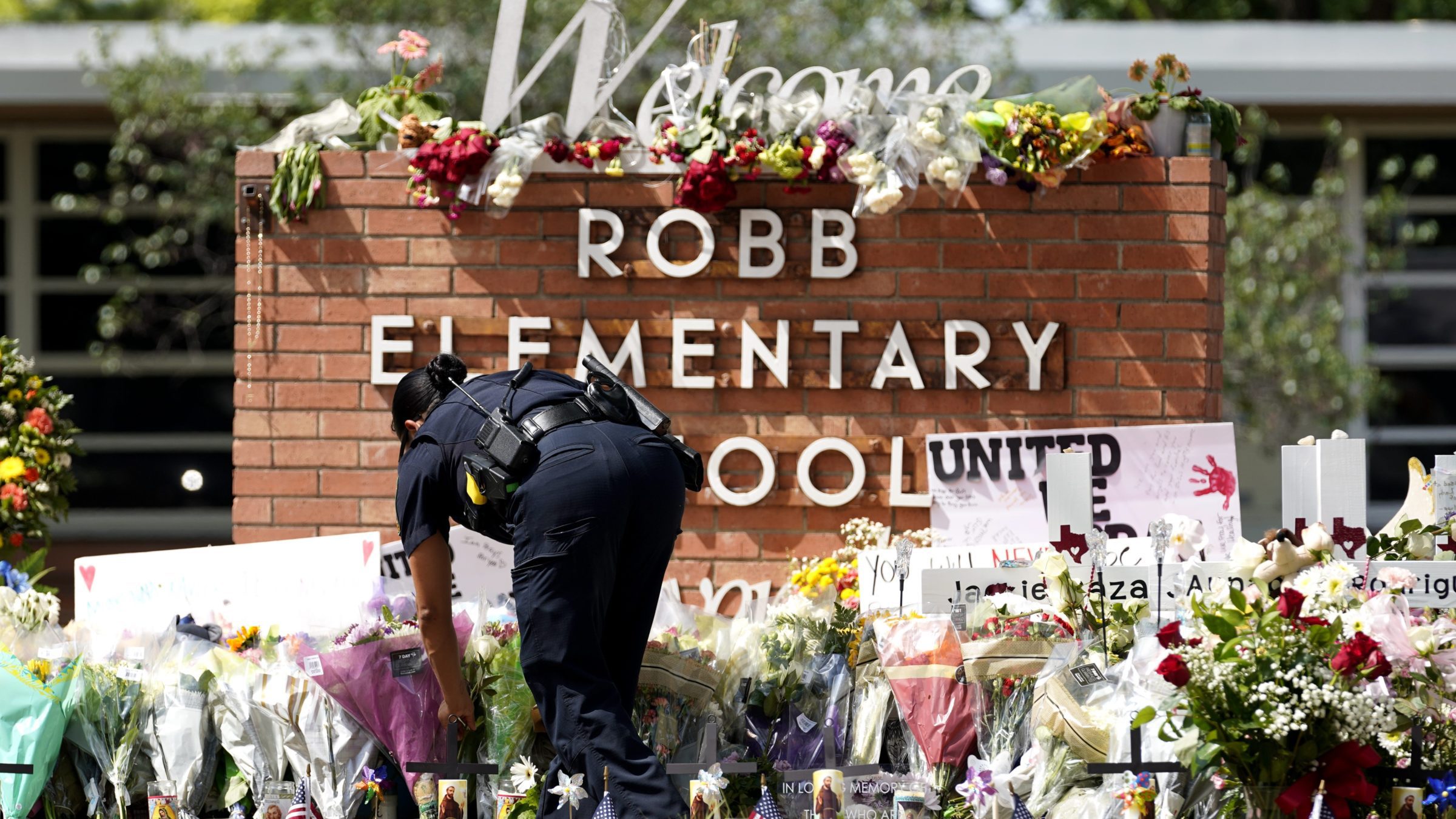

(Photo by Wu Xiaoling/Xinhua via Getty Images)

Instead of acknowledging policing’s failures to keep people safe, the Court’s conservatives seem to prefer the National Rifle Association’s “good guy with a gun” fantasy. Although Justice Antonin Scalia’s opinion in Heller purported not to cast doubt on the validity of gun control measures, Justice Samuel Alito sounded very skeptical during Bruen oral argument, painting a dystopian picture of a New York City in which armed assailants lurk around every corner. Restricting the right to carry, in Alito’s view, denies people their right to self-defense and basically guarantees that innocents will be attacked. If only they could protect themselves the way cops do—by shooting at everyone who scares them.

In addition to expanding access to firearms, conservative activists have pushed hard at the state level for “stand your ground” laws, which expand the permissible uses of deadly force. These laws have been shown to not reduce violence, and in certain cases may actually increase it. Social scientists estimate that a Bruen decision striking down New York’s concealed carry law would cause a 13 to 15 percent increase in violent crime. The justices do not seem interested.

The impacts of the Court’s decisions on these issues are not distributed evenly. Studies have confirmed the obvious point that where there are more guns, there is more gun violence. Gun violence impacts communities of color and low-income communities at significantly greater rates than affluent and white communities. Children in poor communities are far more likely to be killed by gun violence, and their risk of death increases along with the poverty level.

Taking the Court’s vision of near-unrestricted access to firearms alongside its opinions that police do not actually need to provide any protection, it is hard not to feel like they are setting up a Thunderdome-style future in which people kill or are killed while the justices, protected by publicly-funded security, look on from the safety of their marbled courtroom.

Fulfilling a “special duty” to protect the public is, according the police, the entire point of having police. Stopping children from being murdered in their elementary school classrooms is one of the only things everyone agrees that cops are supposed to do. But this Supreme Court has no interest in holding police to this bare obligation. Everyone—except police—is worse off because of it.