In August 2020, Jace Coones was incarcerated in a state prison in Colorado City, Texas, when he was hospitalized for heat-induced dehydration. Temperatures inside the prison were regularly in the 90s and 100s. And Jace’s cell, like tens of thousands of others operated by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, had no air conditioning.

A few weeks later, on a day when the temperature in his cell at least equalled the outside temperature high of 106 degrees, Jace again displayed signs of significant dehydration. His resting pulse was 103, he was taking 98 breaths per minute, and his skin was warm but dry, meaning his body likely lacked enough fluid to produce sweat to cool him down. Jace told a nurse that he was too hot, and that he needed to cool off and shower. But she only let him rest on a gurney for a while before making him leave, calling security when he refused to do so out of fear of returning to the hot cell.

A couple days after that, on yet another day exceeding 100 degrees, a different nurse saw Jace “rolling around on the floor naked,” unable to speak, and surrounded by trays of untouched food. The nurse encouraged Jace “to get up and get on with his day,” and advised security to let the medical staff know if his condition got worse.

It got worse: The following morning, Jace Coones was found in his cell, dead of excessive heat exposure. His body weighed 24 pounds less than it did just three days earlier.

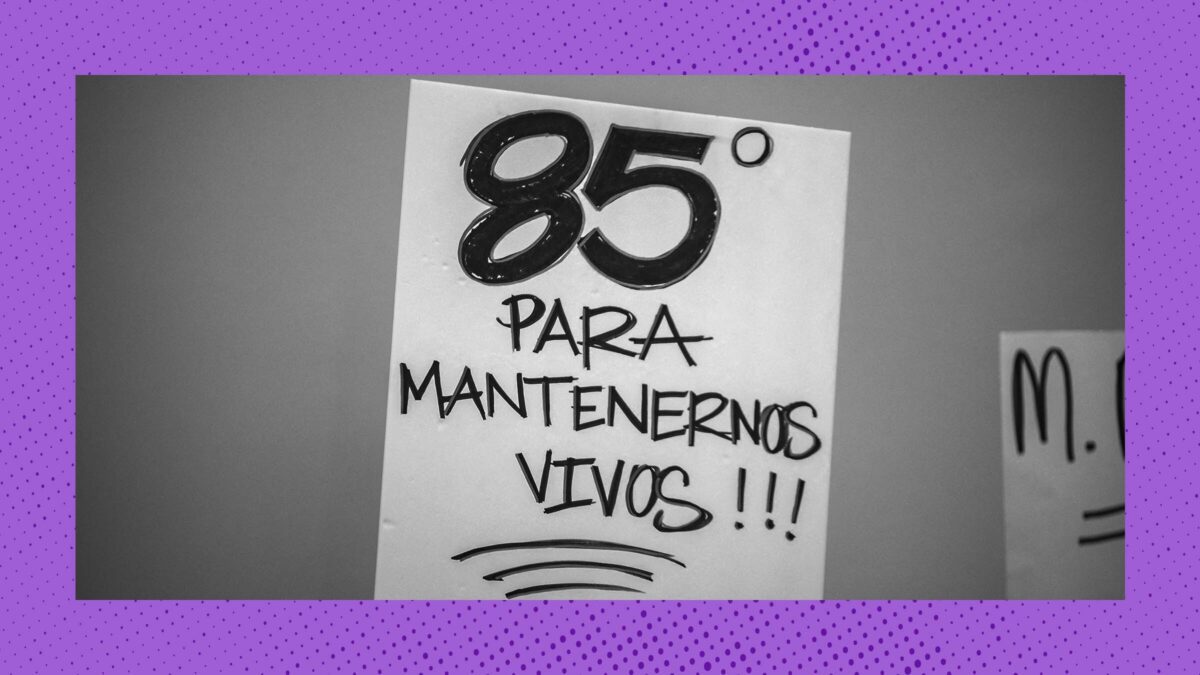

Jace was not sentenced to be broiled alive. Yet a 2022 study found an average of 14 heat-related deaths per year in Texas state prisons without air conditioning between 2001 to 2019. During a hearing last year in a different case, Tiede v. Collier, Texas Department of Criminal Justice Executive Director Bryan Collier admitted that he was aware of 10 deaths from heat stroke in the summer of 2011 alone. And between May and October 2023, people incarcerated in Texas filed over 4,200 heat-related complaints.

For a long time, incarcerated people and their surviving family members have been kept out of court. But that may be beginning to change. The Eighth Amendment of the Constitution prohibits “cruel and unusual punishments.” And even for judges in the country’s most conservative federal appeals court, the worsening effects of climate change are becoming impossible to constitutionally ignore. “Summers are fatal for many Texas inmates,” the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently observed, and “as summers continue to get hotter, the problem continues to get worse.”

Cynthia Coones, Jace’s mom, sued an array of people and institutions responsible for her son’s care and claimed that they violated his rights under the Eighth Amendment. The district court dismissed the lawsuit for failure to state a claim, which means Coones didn’t provide enough facts to plausibly warrant the court’s relief. But on July 25, in Coones v. Cogburn, the Fifth Circuit reversed the dismissal in part: Jace’s mom will now be able to at least make the case in court that the two nurses, the prison warden, and the executive director of the state’s criminal justice department infringed her son’s right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment.

To make an Eighth Amendment claim, a plaintiff has to allege a sufficiently serious deprivation of rights carried out with “deliberate indifference” to their health or safety. In Coones, the Fifth Circuit explained that the “open and obvious nature” of the “brutality of the Texas heat” alone would have been sufficient to show that defendants knew there was a substantial risk of harm. “Defendants would have been reminded of it every time they stepped outside,” said the court in an unsigned opinion, noting the 271 heat deaths in Texas prisons between 2001 and 2019.

Coones also pointed to “the many lawsuits regarding the extreme heat in Texas prisons.” As early as 2015, for instance, the Fifth Circuit already considered it “clearly established” under the court’s precedent that “the Eighth Amendment guarantees inmates a right to be free from exposure to extremely dangerous temperatures without adequate remedial measures.”

The Coones court also discussed Tiede v. Collier, in which Collier, the TDCJ executive director, admitted to his knowledge of heat-related deaths. In that case, in a March 2025 order, Judge Robert Pitman denounced “the plainly unconstitutional treatment of some of the most vulnerable, marginalized members of our society.” In Pitman’s view, the “excessive heat” in TCDJ facilities violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishments, and “the heat will only get worse with climate change.”

Plaintiffs like Cythnia Coones still have a long road ahead in their pursuit of justice. But the courts’ acknowledgment that climate change is making the state’s prisons unconstitutionally hot represents a significant step forward for prison climate litigation. Judges and lawmakers alike have erected substantial barriers between incarcerated people and their ability to actually vindicate their rights. That makes it all the more notable when some start to crumble.