In the opening scene of The Wire, a distraught young man explains to a detective that his friend, Snot Boogie, had just been murdered because of his habit of stealing money from the weekend craps game. Something about the story did not make sense to the detective. “Every time?” he asked. “If Snot Boogie always stole the money, why’d you let him play?” The young man replied, “Got to. This America, man.”

Clip via YouTube

The show played it for grim laughs, but two decades later—after officials in Colorado and Maine removed former President Donald Trump from their state primary ballots, an issue the Supreme Court will consider later this year—the Snot Boogie Theory has been gaining traction in academic circles, and not just among stoned freshmen during late night bull sessions. Sure, Trump may have suggested the 2012, 2016, and 2020 elections were all rigged, and may already be claiming the 2024 election is rigged and threatening violence if he loses. And sure, the Constitution may say he is no longer eligible to be president as a consequence of his own actions. But, the argument goes, the country must nonetheless reckon with him at the ballot box once again. Got to. This America, man.

Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment bars anyone from holding “any office” in government who, “having previously taken an oath” to defend the Constitution “as an officer of the United States,” subsequently engaged in “insurrection.” The legal justification for removing Trump from the ballot is simple enough to understand: Donald Trump took such an oath upon his inauguration in 2017 and subsequently engaged in insurrection when, having lost the 2020 election, he nonetheless attempted to remain in power. He pressured local officials to “find” non-existent votes, manufactured fraudulent electoral college votes, and ultimately incited violence on January 6, 2021 in an effort to force lawmakers and his vice president to recognize those fake electoral votes. Therefore, he is ineligible to be president a second time.

That is not to deny how fraught it is to remove a leading candidate from the ballot. But the Colorado courts treated the issue with appropriate weight: A state court held a five-day trial, heard arguments from Trump and others, and considered extensive evidence before determining that Trump engaged in insurrection; last month, the Colorado Supreme Court affirmed. This is unsurprising, as up until a few months ago, it was such a non-controversial way to describe the riot that even Mitch McConnell called it a “violent insurrection.” The Colorado Supreme Court’s analysis of Section 3 is likewise carefully reasoned but in keeping with common sense. It found the text to be clear: “We generally turn to historical and other extrinsic evidence only when the text is ambiguous, which it is not here,” the majority wrote.

Trump speaks with supporters shortly before they began marching to the Capitol on January 6, 2021 (Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

In Maine, the procedure was different, but the results were the same. There, the Secretary of State, Shenna Bellows, held a hearing and determined that Trump is not qualified to be president under the Fourteenth Amendment, and as such, his representation of his eligibility on his candidate consent forms was false. Trump has appealed that ruling in state court.

The legal counterarguments are not particularly persuasive. They include clumsy efforts at redefining insurrection into something completely unrecognizable, or claiming that the President of the United States is not an “officer” of the United States. But, as the Colorado Supreme Court noted, “The Constitution refers to the Presidency as an ‘Office’ twenty-five times.” In a recent law review article on the subject, professors William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen came to a fairly unambiguous conclusion about Trump’s ineligibility. “If the public record is accurate, the case is not even close,” they write. “All who are committed to the Constitution should take note and say so.”

The sharper critics of the Colorado and Maine decisions tend to bypass legal arguments altogether. Their move is to claim that Section 3 is not sufficiently clear to demand Trump’s disqualification, and then offer a string of political justifications for keeping Trump on the ballot while claiming any other approach is undemocratic—that is, the Snot Boogie Theory of constitutional interpretation.

For example, Samuel Moyn, a left-leaning professor at Yale Law School, wrote in The New York Times that disqualifying Trump “would be the wrong way to show him to the exits,” because it “could put democracy at more risk rather than less.” Moyn also argued that it “could make him more popular than ever.” These are not legal arguments about what the Constitution requires; they are political arguments about why the Court should ignore the very clear requirements of the document in order to prevent violence and public unrest. Moyn is arguing, in short, that the Supreme Court should read Section 3 out of the Constitution because the implications of applying it concern a tenured Yale law professor.

Eric Segall, another left-leaning law professor, also believes Trump must remain on the ballot, for largely the same political reasons as Moyn. In Jurist, he focuses on a clause of Section 3 that allows Congress to grant anyone an exemption from the insurrection ban by a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate. So Segall rightfully directs his argument to Congress, rather than the Court, saying Democrats and Republicans should come together and “pass a bill” to ensure that the man who tried to have his own vice president murdered gets another shot at the presidency. According to Segall, “This strategy will be perceived by most Americans as strong and aggressive and will help Democrats keep the White House.”

Segall is correct that Congress is the proper institution for making such political decisions. But he omits any discussion of the possibility of violence with Trump on the ballot—an important political consideration!—or the fact that Congressional Democrats would almost certainly never sign on to granting Trump an exemption. For one thing, after January 6, all 48 current Democratic senators who were in office at the time, as well as four current Republican senators, voted to convict Trump of inciting insurrection, stating that he “will remain a threat to national security, democracy, and the Constitution if allowed to remain in office” and “thus warrants…disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States.” Segall offers no description of what has transpired in the last three years to make this conclusion any less true, let alone how any of these 52 Senators would explain a complete reversal of their position. Failing to consider the role of the people’s elected representatives (Moyn) or how those representatives are likely to behave and why (Segall) puts the lie to the notion that what is being defended here is “democracy” in any meaningful sense.

Trump supporters hang a noose from a makeshift gallows built on the National Mall, January 6, 2021 (Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images)

Lastly, in The Washington Post, Ruth Marcus argues that the Court must overturn the Colorado decision to avoid “chaos,” and essentially offers a prescription for the form the overturning should take. According to Marcus, it should be unanimous; Justice Clarence Thomas should recuse himself; and the justices should avoid giving Trump’s “appalling behavior” on January 6 the cover of First Amendment protections. They should instead say, Marcus argues, that congressional legislation is required to enforce Section 3. (Never mind that the language of Section 3 only requires Congress to act in order to grant exemptions, and so this argument turns the entire provision on its head.) Of course, it turns out Thomas did not recuse himself from considering whether to hear the Colorado case, and will almost certainly not recuse himself from the merits decision either.

This disconnect between what Marcus believes would be the most legitimacy-enhancing approach and what actually happened reveals the fundamental flaw in these columns and many others like them: building an argument on magical thinking. Even if you wish really hard, Clarence Thomas is not going to recuse himself from this case; Donald Trump is not going to stop claiming everything is rigged because the liberal justices joined an unanimous opinion; and Senate Democrats are not going to betray every single warning they’ve raised about Trump being a threat to democracy for the past eight years to give him a special exemption from the Constitution’s insurrection ban. Donald Trump exists in the real world, not a law school exam hypothetical, and strategies for opposing him need to be rooted in reality.

And in reality, the threat of violence will be the same (or higher) with Trump on the ballot than with him off it. We know this because Trump was already on the ballot in 2020, when voters showed him the “correct” exit from the American political system by a seven million-vote margin. This did not forestall violence. Instead, Trump incited it. Someone placed pipe bombs at the headquarters of both political parties when Congress convened to count the electoral votes. That same day, angry rioters viciously beat Capitol police and stormed the building. One government witness said that, had they been given the chance, the Proud Boys would have killed Vice President Pence.

The passage of time has not made Trump supporters any less sanguine about the results. Two years after Trump left office, a man who believed Nancy Pelosi stole votes to elect Joe Biden broke into her home intending to kidnap her and instead attacked her husband with a hammer. Trump has promised “bedlam” and refused to rule out violence in the coming election; the special prosecutor who indicted Trump is currently under such credible threats that he is being protected by U.S. Marshals. When it comes to preventing violence from Trump supporters, “leave it to the voters” is quite literally the only approach that has a proven track record of failure, which is precisely why the Fourteenth Amendment is even available as a remedy here. Moyn, Marcus, et al.’s prescription for the disease currently eating away at American politics is no treatment at all.

Trump’s more recent threats of violence are ostensibly motivated by the criminal charges brought against him, which raises an important question. If the courts are simply not up to the task of determining whether his behavior on and leading up to January 6 triggers the Constitution’s insurrection ban, can they be trusted to determine if those same actions carry criminal liability? It is not obvious that an election with Trump on the ballot but out on bail awaiting sentencing is the most democracy-enhancing scenario, let alone one likely to avoid violence. Or perhaps the next move is to pen op-eds begging the Court to delay Trump’s criminal trials until after the election, leaving his criminal liability “to the voters” as well.

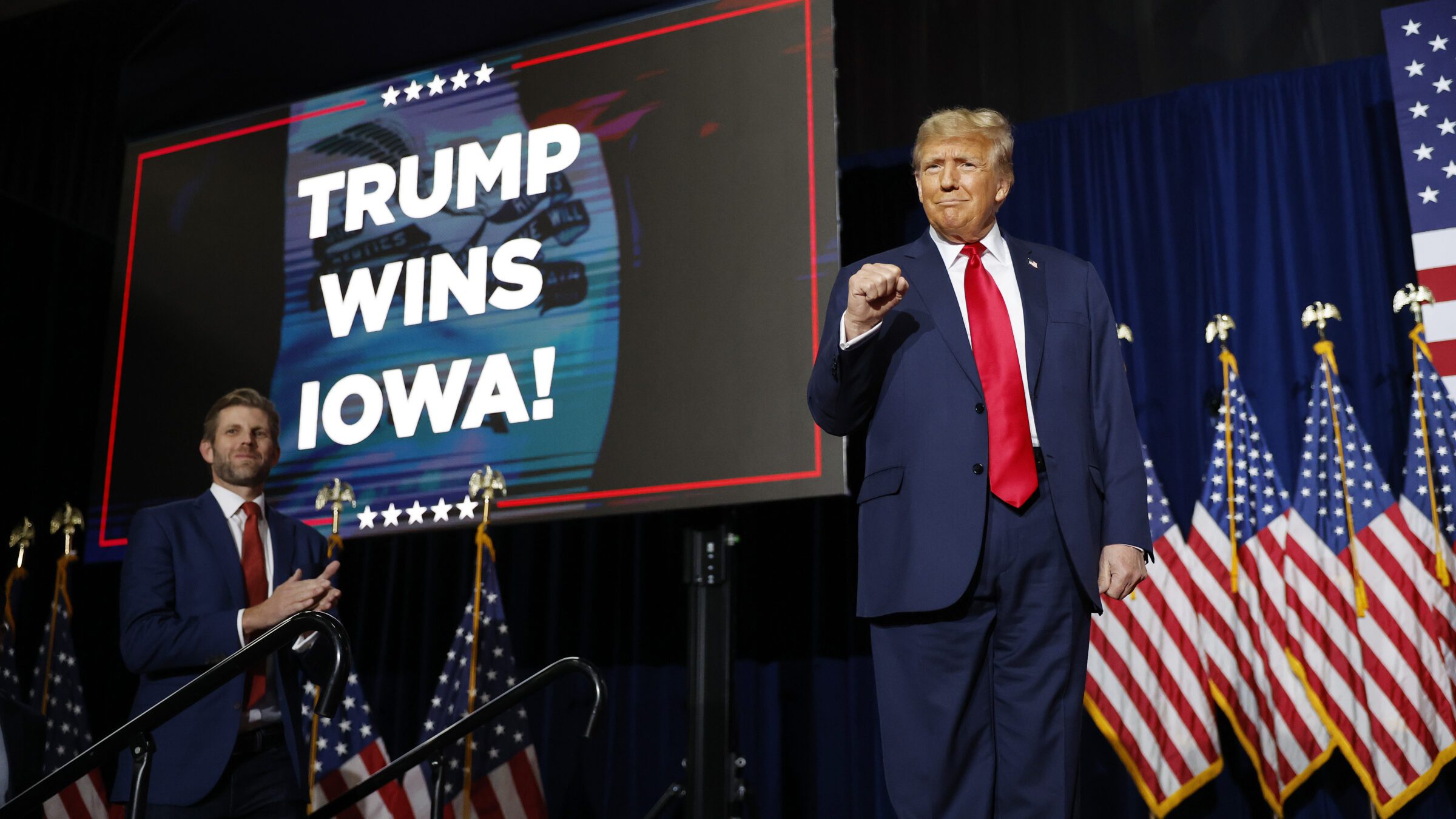

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Of course, the voters writ large do not actually decide who becomes president, because the Constitution sets out plenty of rules limiting their discretion. For one recent example, the majority of voters preferred Hillary Clinton in 2016 by a margin of 3 million votes. The Electoral College is a particularly noxious anti-democratic feature of our Constitution, but curiously not one that generates a parade of editorials calling on the Supreme Court to write it out of existence. Similarly, Trump might not even be the favorite to win the Republican nomination were, say, Arnold Schwarzenegger eligible to run, but that is also forbidden by the Constitution, because he was not born in the United States.

The main difference between those restrictions on democracy and the insurrection ban seems to be that enforcing them right now does not risk inflaming an angry mob. This also betrays some thinking common in law and politics: the idea that there is a perfect way to do or phrase something that will not incite reactionaries. There are no magic words or magic processes to prevent right-wing reaction—not passing the Reconstruction Amendments, not passing the Votings Rights Act with large bipartisan majorities, not literally defeating them in a Civil War, and on and on. The only way forward is to fight them using every tool at our disposal, which includes holding them accountable when they break the law.

Making the Constitution and the rule of law contingent on not upsetting a right-wing mob is not saving democracy. It is ceding democracy entirely.