For the first time in his three runs for president, Donald Trump won both the Electoral College and the popular vote in 2024. But during his first term and in the four years since, he’s made it abundantly clear that he does not think people’s votes matter. He insisted the results in 2020 were illegitimate, and harassed government officials to “find” fake votes for him. He helped instigate the deadly January 6 insurrection in an attempt to overturn the election results and disenfranchise millions of people. And in the run-up to the 2024 election, he and his campaign filed spurious “election integrity” lawsuits in the courts and hatched “secret plans” with the Republican Speaker of the House to perhaps seize power even if he lost again.

For as much as Trump has already devalued votes, the next votes people cast will matter even less. Conservative elites have spent decades whittling away at the Voting Rights Act, which was once a robust tool to protect the ability of people of color to participate in the political process. In a second Trump term, the few protections left will crumble, and free and fair elections will be pushed further out of reach.

The Voting Rights Act is a landmark piece of legislation enacted by Congress in 1965 in order to finally enforce the Fifteenth Amendment’s prohibition on racial discrimination in voting. The VRA dramatically increased Black voters’ access to the ballot and representation in government: After the 1966 election, for example, the number of Black elected officials in the South jumped from 72 to 159, and within four years of the Act’s passage, nearly 1 million Black people were registered to vote. The VRA’s passage also had significant downstream effects, like more public infrastructure spending in Black communities and fewer baseless arrests of Black residents. The Act remains one of the most important federal laws for protecting voters against discrimination and making self-governance a reality for marginalized people.

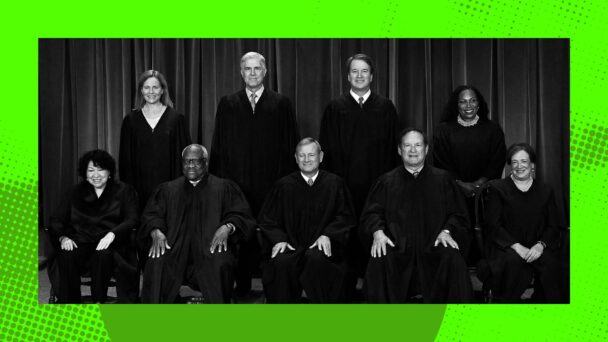

Thanks to the Supreme Court, however, the Voting Rights Act is not what it used to be. Section 5 of the law requires electoral districts with a history of racist voter discrimination to “preclear” changes to their voting policies with federal courts or the Department of Justice, so the federal government could ensure that such changes were legal. And Section 4 of the VRA laid out a formula to identify which jurisdictions Section 5 covers. But in 2013, the Supreme Court decided in Shelby County v. Holder that Section 4’s formula was unconstitutional. Since there’s now no formula establishing where preclearance applies, preclearance doesn’t apply anywhere. For the past decade, there has been no check on discriminatory policies before they go into effect.

(Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Section 2, courts are supposed to consider the “totality of the circumstances” to determine if a policy causes members of minority groups to have less opportunity to participate in the political process. Yet in 2021, the Supreme Court abandoned Congress’s instruction in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee. Instead of taking everything into account, the Court declared that judges shouldn’t give much weight to factors like—I wish I were joking—a district’s history of racial discrimination. Conveniently for elected officials who want to suppress the vote, the Court’s new standard makes it much harder for voters to challenge discriminatory laws.

To make matters worse, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas hinted in a concurring opinion in Brnovich that perhaps voters shouldn’t be able to bring Section 2 claims at all. They instead suggested that under the statute, only the federal government is authorized to root out discrimination and file lawsuits to enforce Section 2. Conservative judges in the lower courts have picked up the justices’ signal: Last year, a federal appeals court held that regular people have no right to challenge racist, illegal voting laws to which they may be subjected.

This is a five-alarm fire for voting rights because regular people have been primarily responsible for enforcing the Voting Rights Act for decades. Fewer than ten percent of all successful Section 2 cases in the past 40 years have been brought by the federal government alone. People know when they’re being discriminated against in their local communities, and are highly motivated to protect their rights. But the overburdened Department of Justice can’t be everywhere at once, making it ill-positioned to investigate every possible violation.

Recent history also demonstrates that a Trump-led federal government cares little for doing this work in the first place. His Department of Justice didn’t file a single new case under the VRA until late May 2020, and when it did deign to get involved, it argued in defense of voter restrictions and against people of color, repeatedly reversing the government’s position in cases that began before Trump took office. In one case about a voter ID law in Texas, for instance, Trump’s DOJ suddenly withdrew an intentional discrimination claim that had been litigated for nearly six years—without telling the attorneys who actually worked on the case. (Trump’s appointees to the DOJ asked career DOJ attorneys to sign the new briefs as a show of continuity; they refused.) Relying on government enforcement alone can mean no enforcement at all if the federal government doesn’t care about civil rights.

This leaves voters of color facing a nightmare scenario. There’s no Section 5 to block racist laws from going into effect. They may not be able to use Section 2 to strike down racist laws already in effect. And the only actor who can certainly use Section 2—the Trump administration—has no interest in doing so. The Voting Rights Act has been on life support for years, and a Trump White House is all set to pull the plug. If his administration treats enforcement of the VRA as it did before, the Constitution’s command to confront racism in the political system could become nothing more than a nice idea.