When Congress amended the Voting Rights Act in 1982, it recognized that having the right to vote and having the ability to vote are two different things. Tens of millions of American adults, for instance, struggle to read English at a basic level, and around one in six eligible voters have a disability which may make it difficult to vote independently. Because of barriers like these, Congress provided in Section 208 of the VRA that any voter requiring assistance because of “blindness, disability, or inability to read or write” could receive such assistance “by a person of the voter’s choice.”

Notwithstanding Section 208, Arkansas enacted a law in 2009 that made it a misdemeanor for anyone other than an election official to assist more than six voters in marking and casting their ballots. At the time, Democrats controlled Arkansas’s state government and pushed the law in response to an investigation of fraud allegations in a 2006 runoff election. Currently, Republicans are in control and contend that the six-voter limit is a “structural defense” against “undue influence” and “abuse of this exceptional accommodation by would-be professional voter assistants.” Regardless of intent, the effect of the law is the same: If a voter chooses someone to help them who has already helped six voters, then voter number seven is out of luck.

Arkansas United, a nonprofit organization that assists voters with limited English proficiency, challenged the law on the eve of the 2020 election, and won a federal court order blocking the statute in time for the 2022 midterms. But the Eighth Circuit paused the order while the state appealed, which let the law remain in effect. And on Monday, a panel of three Republican-appointed judges decided the appeal in the state’s favor, ruling in Arkansas United v. Thurnston that the nonprofit never had a right to sue in the first place.

“Section 208 speaks only of the assistance that a voter may be given,” said Judge L. Steven Grasz for the court. “It is silent as to who can enforce it.” The Eighth Circuit concluded that “the text and structure” of the VRA provision “do not create a private right of action,” so Section 208 can only be enforced by the Attorney General of the United States, at their discretion.

The current Attorney General, Pam Bondi, has shown no such desire. Under her leadership, President Donald Trump’s Justice Department has purged the department’s voting section of career civil rights attorneys, dismissed cases challenging voter suppression, prevented new cases from being filed, and literally rewritten its mission statement to focus on rooting out virtually nonexistent voter fraud instead of enforcing foundational civil rights statutes like the VRA.

No modern legislation has done more than the Voting Rights Act to actually vindicate the constitutional guarantee of freedom from discrimination in voting, ensuring that people have an equal opportunity to participate in the political process. And for this reason, the conservative legal movement has spent decades devastating the VRA’s capacity to protect multiracial democracy. Supreme Court decisions like Shelby County v. Holder and Brnovich v. DNC have struck down or significantly curbed core pieces of the statute, limiting what it can do. And administrations like Trump’s are unwilling to do even that.

These constant attacks have left voters on their own. By issuing decisions like Thurnston finding no private right of action, the Eighth Circuit is trying to make sure the only people willing to protect voters can’t do so.

The Eighth Circuit’s first major retreat from the VRA’s purpose was in its 2023 decision Arkansas State Conference NAACP v. Arkansas Board of Apportionment. In that case, the Arkansas NAACP and other organizations alleged that the state’s electoral district maps violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by diluting Black voting strength. There too, the Eighth Circuit decided that the “text and structure” of Section 2 did not create a private right of action. This was a particularly shocking conclusion since people across the country have sued under Section 2 of the VRA and won over 165 times since its enactment, and the Supreme Court has regularly made reference to Section 2 as privately enforceable. But according to the Eighth Circuit, these decisions made unwarranted “background assumptions” that the court, in its wisdom, saw fit to disregard.

The Eighth Circuit struck another blow against voters’ ability to protect themselves in Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians v. Howe. In 2021, North Dakota adopted a redistricting plan that diluted Native Americans’ voting strength by packing members of the Turtle Mountain Band into one district and cracking members of the Spirit Lake Tribe across others. Cut off from a straightforward VRA remedy under Arkansas Board of Appointment, Native voters sought to enforce their Section 2 rights under Section 1983, a federal law which lets people sue state officials who violate their federal rights. They won and the district court imposed a new nondiscriminatory map. But two months ago, on appeal, the Eighth Circuit directed the lower court to dismiss the case and held that voters couldn’t use Section 1983 either: According to the divided panel, not only does Section 2 not create a remedy, it “does not unambiguously confer an individual right,” so there’s nothing for Section 1983 to enforce.

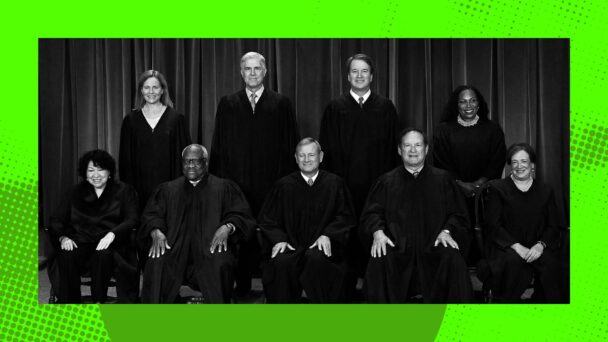

The challengers then filed an emergency petition, which the Supreme Court granted on Thursday—which means that, at least for now, Section 1983 remains a feasible (if roundabout) way to enforce the Voting Rights Act in the Eighth Circuit. But Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch all noted they would have denied the application. Doing so would have left Native voters without a right or a remedy.

For generations, the Constitution’s prohibitions on racial discrimination in voting went unenforced—a right on paper, but not in practice. Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act to fix that, but conservative judges are in effect recreating the conditions that gave rise to the VRA to begin with. The federal government is again retreating from civil rights litigation and, on top of that, it is refusing to let victims of discrimination bring their own lawsuits. Conservative judges’ spurning of individual enforcement of the Voting Rights Act is again rendering people of color’s constitutional right to equal political participation null and void.