The Fifteenth Amendment, which bars discrimination against voters on the basis of race, was ratified in 1870—but nearly a hundred years after that, those were just words on paper. Black voters were still broadly disenfranchised well into the 20th century, facing significant legal obstacles in addition to the threat of violence. It took the Voting Rights Act, which was enacted 59 years ago this month, to begin to fulfill the Constitution’s broken promise.

The anniversary of the Voting Rights Act should be an occasion to celebrate. After all, at first, the VRA was dramatically successful in expanding access to the ballot and protecting the ability of communities of color to participate in self-governance. But over the last 15 years, the Supreme Court has struck down key provisions of the Act—and made it harder to protect voting rights with the provisions that the Court left intact.

The decisions undermining the Voting Rights Act can’t be credibly explained by the Court’s standard justifications for striking down legislation. The reasoning is so egregious that in their new books, journalist David Daley, author of Antidemocratic, and law professor Josh Douglas, author of The Court v. The Voters, describe the Court as “basically making things up” and “basically making up the law.” The justices’ cobbled-together rationales evince the Court’s disdain for the idea that racial justice is the government’s responsibility, and its contempt for multiracial democracy itself.

The Court’s first major step in setting the VRA up for failure was a 2009 case called Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder (NAMUDNO). Section 5 of the VRA required electoral districts with a history of racial discrimination in voting to “preclear” changes to their voting policies with the federal Department of Justice. Texas was subject to Section 5, but in NAMUDNO, a utility district within the state argued that it didn’t have a history of discrimination, and should thus be able to apply for an exemption. Alternatively, the district argued, if Section 5 did not allow for such an exemption, Section 5 must be unconstitutional.

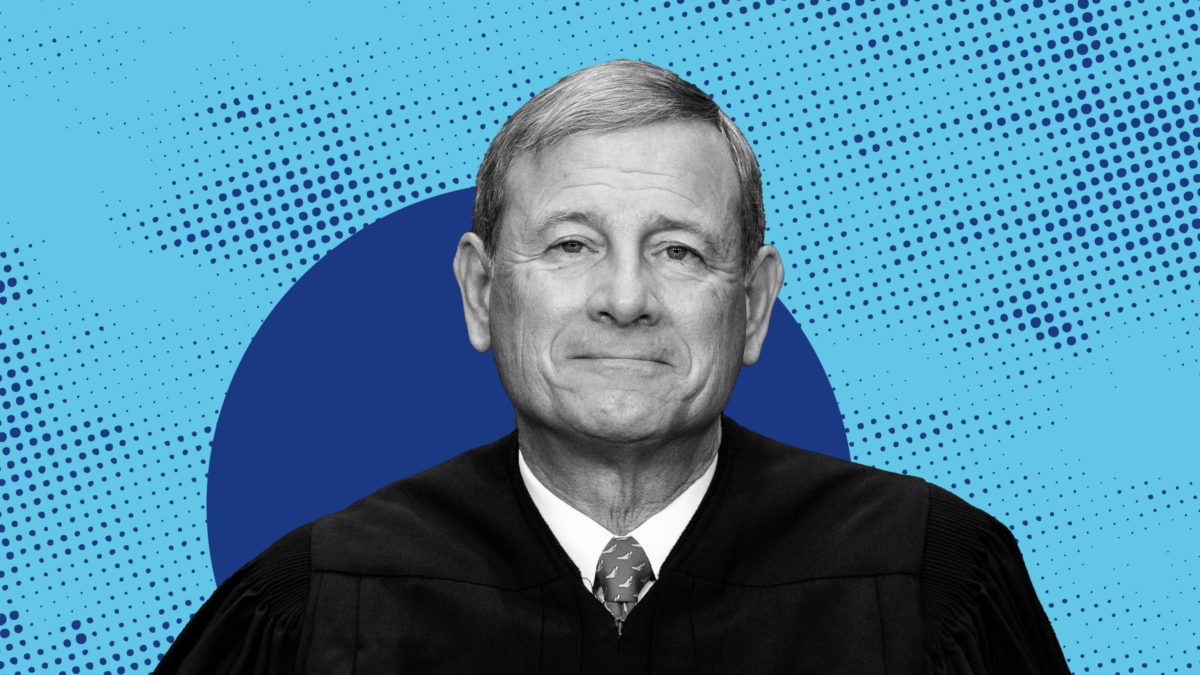

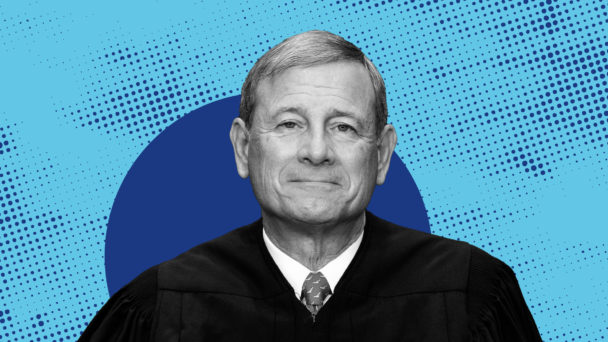

The Court’s opinion avoided the latter question, but strongly hinted that Section 5 was not long for this world. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts emphasized that the “federalism costs” of Section 5 gave rise to “serious misgivings” about its constitutionality, suggesting that the VRA made the federal government too involved in state and local affairs. He also claimed that treating some states differently than others departs from a “fundamental principle of equal sovereignty,” which is particularly bold because no such “principle” existed. The closest thing Roberts could find to support it were two pre-Civil War cases that the Court invoked in Dred Scott, the notorious ruling that declared the government unable to confer citizenship on Black people. (I discuss this at length in The Originalism Trap.)

Roberts also fussed over the VRA’s lifespan, describing Section 5 as a temporary solution to an extraordinary problem that America had ostensibly moved beyond. “Things have changed in the South,” he wrote, asserting that “blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees are rare.” Astute readers will note that “rare” is not “nonexistent,” and that his formulation would more or less ignore the persistence of discrimination that is anything less than “blatant.”

When the racism is merely subtle (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call)

If NAMUDNO was the pass in an antidemocratic alley-oop, Shelby County v. Holder (2013) was the dunk. In Shelby County, the Court quoted the nonsense it first trotted out in NAMUDNO as justification to strike down Section 4 of the VRA, which identified the districts with histories of discrimination to which Section 5’s preclearance requirements applied. Shelby County didn’t technically strike down Section 5, but it might as well have done so: Declaring the formula in Section 4 unconstitutional made Section 5 unusable, and freed states to implement new discriminatory policies without federal supervision.

The opinion in Shelby County demonstrates what Daley characterizes as “general impatience” for the end of Section 5, which, Roberts said, was “intended to be temporary.” It relies on misleading statistics that downplay the continued presence of racial discrimination in voting, hyping up a vanishing racial turnout gap without acknowledging that President Barack Obama’s election was a historical outlier. “Our country has changed,” Roberts wrote, as if voters of color must pay for white people’s misplaced optimism about how long it would take to end racism.

Finally, Roberts understated the harm of nullifying Section 5 by pointing out that a different part of the Voting Rights Act, Section 2, remained good law. While Section 5 prevented new racist laws from taking effect in covered jurisdictions, Section 2 put a stop to racist laws in effect at the time of the Act’s passage, by generally barring state and local governments from doing things that deny the right to vote on the basis of race. “Section 2 is permanent, applies nationwide, and is not at issue in this case,” Roberts wrote.

This reprieve was as temporary as it was illusory. In 2021, the Court decided Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, creating impossibly high hurdles for voters looking to defend their rights under Section 2. Before Brnovich, courts deciding Voting Rights Act cases would examine the “totality of circumstances” to determine whether a challenged process was “equally open to participation” by members of a minority group.

But in Brnovich, Justice Samuel Alito, joined by the five other Republican justices, invented a set of “guideposts” that judges should consider—and, just as importantly, specified the factors that judges could safely ignore. If a state claims to be worried about voter fraud? Per Alito, that matters. A history of racial discrimination? Not so much. As Daley and Douglass emphasize, the Court made this up out of whole cloth, presuming the innocence of Republican politicians and ignoring the lived reality of people of color who just want to participate in democracy on equal footing.

The Voting Rights Act is still on the books today. But thanks to these cases, it is functionally impossible to use the Act to stop a discriminatory law from going into effect, and much harder to do anything about discriminatory laws that are already in effect. As a result, voters of color are more vulnerable to racial discrimination than they were sixty years ago. And the fault lies directly with the Republican justices on the Supreme Court.