Prominent conservatives are celebrating Black History Month by graciously allowing Black women attorneys like me to live in their heads rent free as President Joe Biden prepares to nominate one of us to the Supreme Court. The backlash has ranged from obviously despicable suggestions that Black women are inherently unqualified to more insidious complaints that selecting a qualified Black woman is fine, but an announced intent to select a qualified Black woman is not.

But the admission that the nominee would be qualified underscores that qualifications were never the real issue. Instead, the choice to put a Black woman on the Court has sent the white wing into a tizzy because it upends two core components of American mythology: first, that the system promotes true meritocracy, not white mediocrity, and second, that simply ignoring race will make racism go away. These myths are the foundation for a legal system that perpetuates inequality under the guise of neutrality, promising a level playing field but delivering an Olympic ski slope.

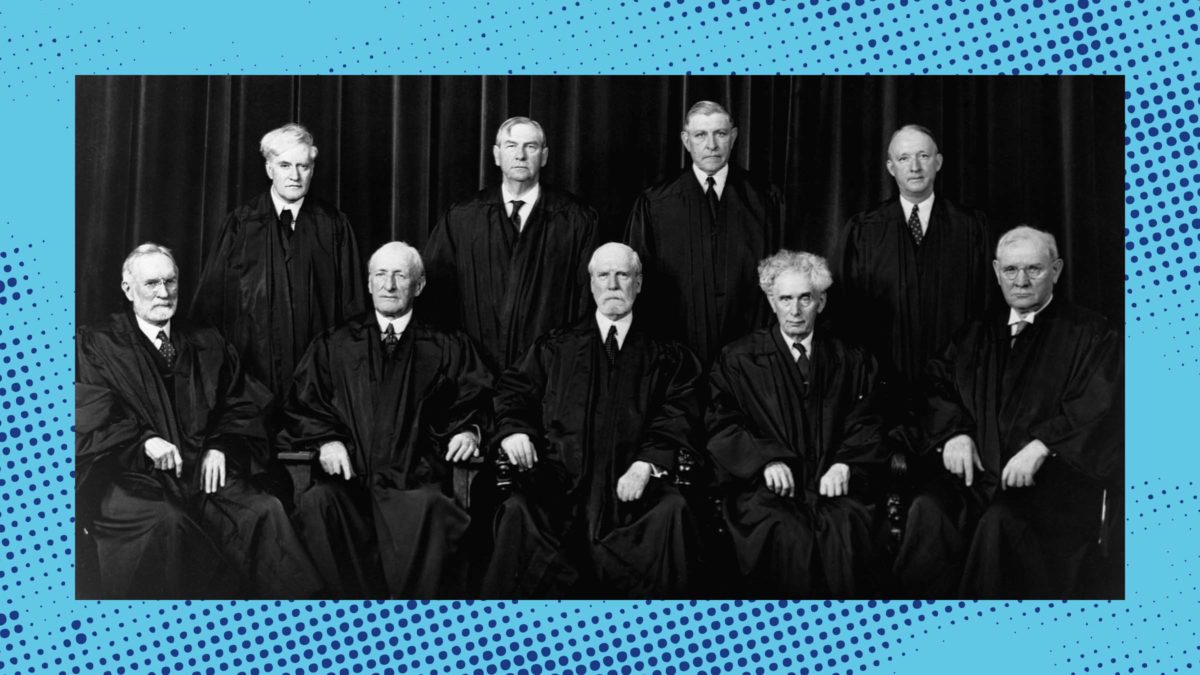

It is not for lack of “qualifications” that Black women have always been excluded from the Supreme Court. For most of the Court’s history, the primary qualifications were “low melanin and high testosterone.” The data is outlandishly stark. White men make up about 30 percent of the country’s population today, but account for about 94 percent of all Supreme Court justices. Nearly twice as many white guys named John have been Supreme Court justices as the combined number of people of color and white women to have ever served on the Court. The Marvel Cinematic Universe, iPhones, and Shrek The Musical all predate the presence of a woman of color on the Supreme Court.

Now, deliberately departing from the historical norm of wealthy white male leadership casts a harsh spotlight on the deficiency of this 200-plus-year-old default: it threatens the idea that the pale, male, and stale among us are most fit to make the rules that everyone else must live by. There were no Black people in the room when seven white lawyers decided Black people had no rights that white men were bound to respect (Dred Scott v. Sandford, 1857). There were no openly queer people in the room when five white lawyers decided it was constitutional to criminalize the sex lives of consenting adults in their homes (Bowers v. Hardwick, 1986). And there were no Muslim people in the room when four white lawyers and one Clarence Thomas decided the president had the authority to follow through on his pledge of “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” (Trump v. Hawaii, 2018).

Intentionally selecting a justice who might not uphold assorted oppressive orthodoxies prompts questions about whether that baseline was ever legitimate in the first place. And not everyone wants those questions answered. This is the real reason heads are exploding: There’s a monopoly on power, and its beneficiaries don’t want to share it—or even admit that others deserve to make decisions about the country in which they have a stake, too.

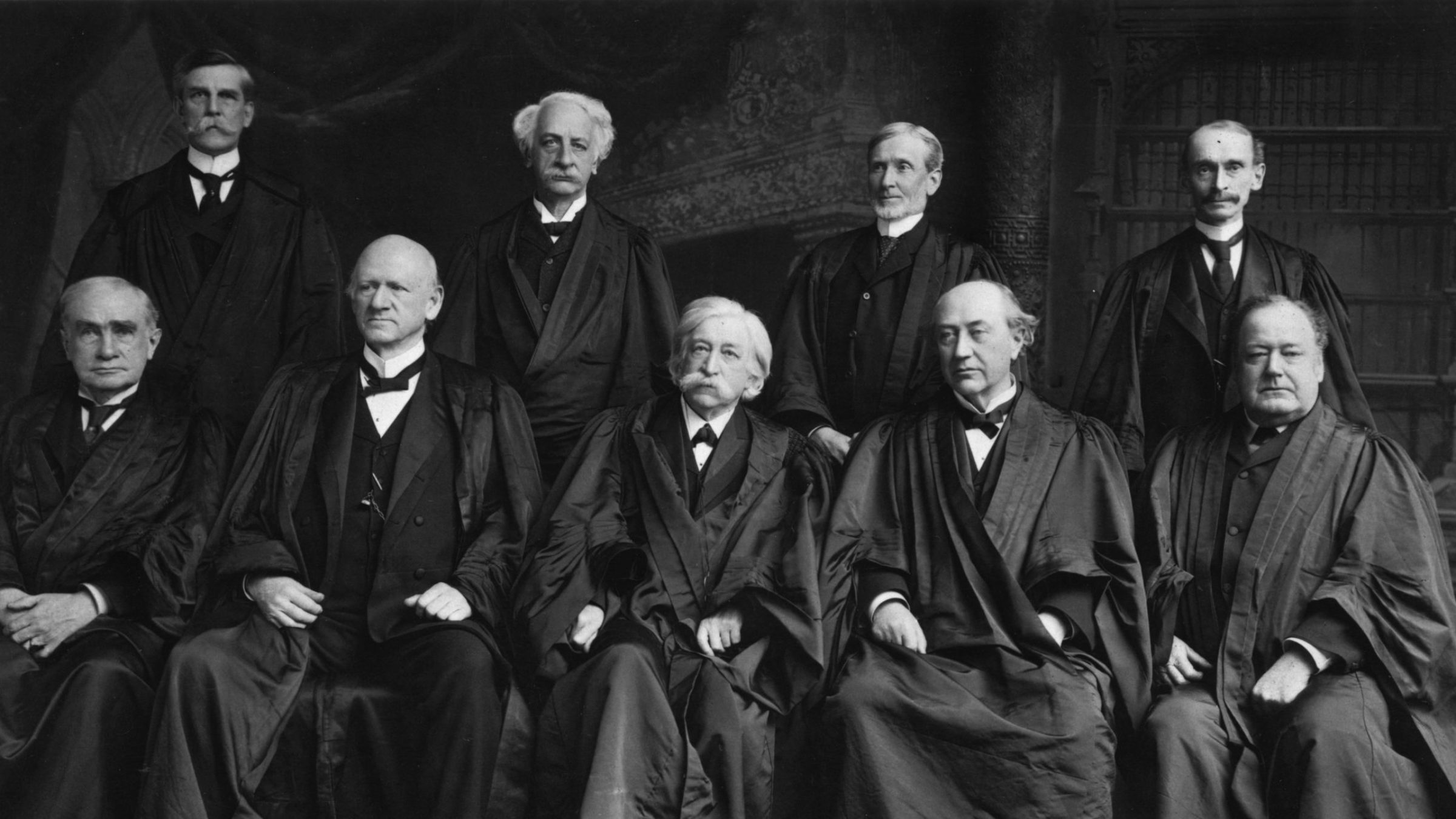

The Supreme Court in 1904 was the very essence of diversity: only one guy named John. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

Many political and legal elites are regrettably non-confrontational about facing the entanglement of law and bigotry head-on. Bigotry, for them, is like Beetlejuice in that it’s only around if you talk about it too much. Chief Justice John Roberts is likely the most well-known practitioner of this school of legal thought. In a 2007 Supreme Court case finding a plan to integrate Seattle public schools unconstitutional, Roberts famously reasoned that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

But the gag is, Roberts didn’t mean “discriminating” as in “subordinating”; in his second usage of the word, he meant “discriminating” as in “making distinctions.” Under this rationale, the harm of racism comes from acknowledging racial classifications, and so attempting to mitigate injuries inflicted on racial lines is just as unacceptable as the actual injury. It’s a rhetorical magic trick, but instead of pulling a rabbit out of a hat, you can pull a legal theory out of your ass and saw the Voting Rights Act in half. Conservative legal elites “avoid racism” by avoiding the explicit invocation of race, and conveniently ignore that explicit and implicit racism both already exist.

It’s this same baby-brained tautological reasoning that makes certain people prickle at the idea of setting out to pick a Black woman for the Supreme Court. In the conservative conception of a “color-blind” society, a decision to address racism and sexism means a decision based on race and sex, which in and of itself is racist and sexist and therefore unacceptable. These critics wrongly consider adding a Black woman to the Court, which is a plan to expand perspectives and broaden who the Court serves, to be just as bad as centuries of keeping Black women off the Court, which was a plan to limit perspectives and constrain who the Court serves. Helping means hurting. Good things are the same as bad things. And a tiny fraction of the country maintains its vise grip on power.

The hysterical reaction to nominating an as-of-yet unnamed Black woman justice is inextricably linked to the conservative project to maintain unearned power over everyone else. To help accomplish its goals, the right has long sought to redefine discrimination and prevent honest consideration of the realities of oppression. And that work is threatened when the nomination of a Black woman spotlights who is helped and who is hurt by the legal system.

So let’s shine that light a little brighter: The deliberate exclusion of the vast majority of Americans from making decisions about issues that affect their lives is an injustice. The promise to put a Black woman on the Supreme Court is a promise to work for a judiciary that better reflects and serves an increasingly diverse country. And though the road is long, it’s an important step towards justice for all.