Nearly 35 years ago, the Senate voted 58-42 to deny Robert Bork a seat on the Supreme Court. Bork, a conservative judge and academic whose work was instrumental to the development of constitutional originalism, had been nominated to the high Court by President Ronald Reagan. His nomination was championed by originalists hoping to secure another foothold on the Court; Justice Antonin Scalia’s appointment had been unanimously confirmed the year before. Instead, the Senate shot Bork down, and they had to settle for Anthony Kennedy, who was unanimously confirmed to the seat the following year.

To most liberals, the ordeal is little more than a bit of political trivia. But to conservatives, the shadow of Robert Bork still looms over American politics. What happened to Bork, they claim, was the original sin of Supreme Court nominations: Democrats had thrown down the gauntlet with their unprecedented and unjust opposition to Bork’s appointment, and the process has been a political battlefield ever since.

What exactly was unfair about Bork’s treatment is unclear. No falsehoods about him were told, nor was his personal life a major topic of discussion. Bork, perhaps more than any other nominee in history, lost on the merits: His rejection was the result of a judicial philosophy far to the right of the average American. He had spent his time as a law professor developing a theory of antitrust law that advocated for minimal government regulation of behemoth corporations and paved the way for the unprecedented levels of concentrated corporate power we see today. In 1963, he wrote an article for The New Republic titled “Civil Rights—A Challenge,” in which he argued that forcing business owners to serve minorities is “a principle of unsurpassed ugliness.” Bork was instrumental in Watergate’s Saturday Night Massacre, where he fired Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox at President Nixon’s request.

The list goes on: Bork did not believe the Equal Protection Clause applied to women (who he claimed, in 2011, “aren’t discriminated against anymore”). He argued that vulgar or explicit art is not protected by the First Amendment, expressly advocating for aggressive censorship of movies, music, and the Internet. He believed that poll taxes and literacy tests for voters were constitutional, and handwaved away the poll tax at issue in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections as “a very small tax.” He had ruled as a federal judge that an employer could force female employees to choose between being fired or being sterilized. He was aggressively homophobic, ultimately spending a sizable portion of his post-judicial career promoting a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage.

Bork was hounded on these topics at his confirmation hearing. When Wyoming Senator Alan Simpson, a Republican, tried to toss him a softball by asking why he wanted to be on the Supreme Court, Bork whiffed: he responded that it would be an “intellectual feast,” giving off the air of an aloof academic (not to mention outing himself as the kind of person who uses the term “intellectual feast”). By the end of the hearings, a majority of Americans opposed Bork’s appointment, and six Republicans would join the Democrats in voting against him.

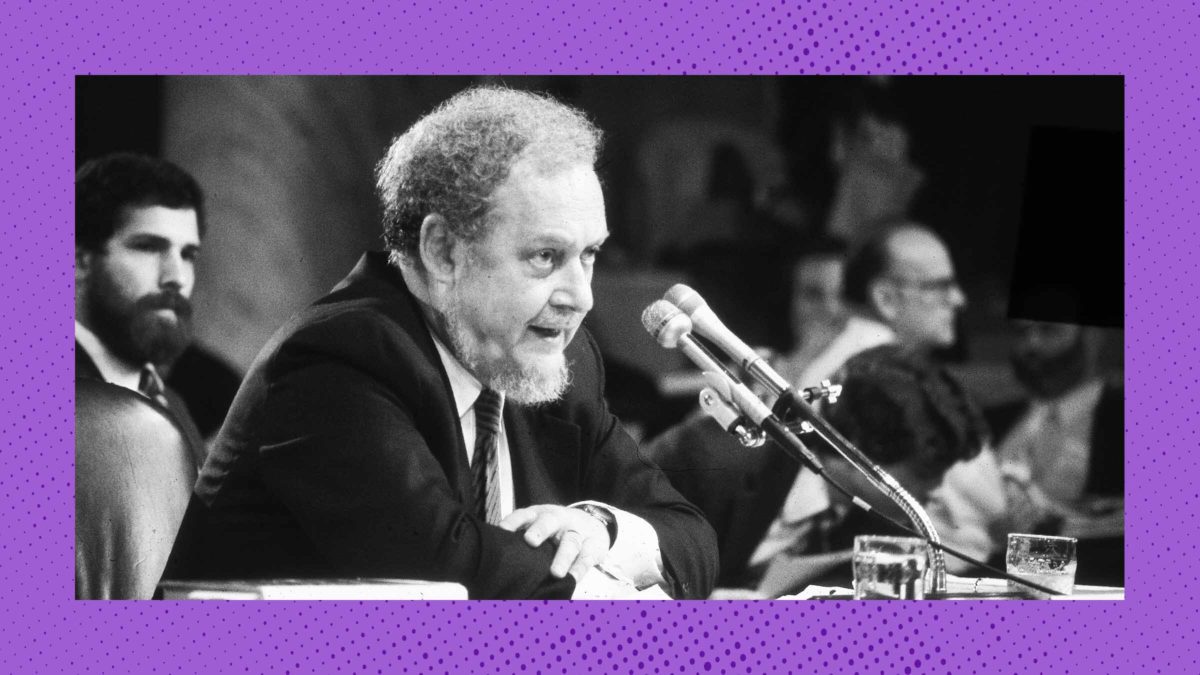

Diana Walker/Getty Images

For his suffering, Bork has become something of a martyr for members of the conservative legal movement. To them, Bork’s defeat was not the result of his fringe ideology, but the output of a Democratic Party that had launched a scurrilous and unprecedented campaign to defeat his nomination.

This narrative does not withstand even a glancing Google search. There was nothing particularly unprecedented about the rejection of a Supreme Court nominee. Bork was not the first nominee to be voted down by the Senate—he was the eleventh, and the third in just twenty years. Nor was this the first time that a nomination was embroiled in political controversy. President Lyndon Johnson’s 1968 attempt to elevate Justice Abe Fortas to Chief Justice was filibustered by Senate Republicans, who insisted that some of Fortas’s fairly commonplace private speaking fees were tantamount to an ethical breach. (Richard Nixon finished that hit job a year later when, in a transparent bid to free up a Supreme Court seat, he opened an investigation into Fortas that eventually led him to resign from the Court). Even before that, the Court had often been the focus of political attention—conservatives spent the 1960s bristling at the liberal holdings of the Warren Court, and “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards sprung up across the South. By the time Bork was nominated in 1987, the Court had been “divisive” for decades.

Why, then, do conservatives still harp on Robert Bork? In some ways the answer is simple. Republicans will never stop talking about Bork because it provides them with something they desperately need: an excuse. The GOP’s conduct in Supreme Court appointments, and their months-long blockade of President Barack Obama’s 2016 nomination of Merrick Garland in particular, was everything they pretend the Bork nomination was: unprecedented, nakedly partisan gamesmanship. Unable to come up with a more substantive justification, they’ve settled for a childhood classic: “You started it.”

But there’s more to the Republican fixation on Bork than just political leverage. To the right, it must be that Bork was treated unfairly, because the alternative is that Americans saw everything Bork stood for—everything conservatives stood for—and were disgusted. Bork was fairly forthcoming about what he believed, both during his confirmation hearing and throughout his career. But candor is not particularly useful when you’re a piece of shit, and it was the Senate’s unobstructed view of Bork’s reactionary beliefs that would sink his nomination.

For conservative lawyers, the real lesson of the Bork nomination was clear: In order for right-wing ideology to be digestible to the public, it needs to be cloaked in the language of legal technicality. Issues of politics and principle—from civil rights to voting rights and reproductive freedom—must be carefully reframed as matters of rote Constitutional interpretation. Conservatives’ concern isn’t about abortion, it’s about the scope of the 14th Amendment. They aren’t trying to stop people from voting, they’re protecting states’ rights to control their own elections. For every reactionary political position, they built a conveniently adjacent legal doctrine.

It is in the nature of reactionary movements that their heroes will often die monsters. When you spend your life standing in opposition to social progress, you risk being on the wrong side of public opinion by the end of it. When Bork came of age, support for segregation was widespread, and the view that homosexuality was degenerate, deviant behavior was mainstream. When he died in 2012, the president was Black, and gay marriage was on the verge of becoming legal nationwide. When the right mourns Bork’s defeat, they’re not mourning the erosion of Senate decorum or the politicization of the Supreme Court. They’re mourning the retreat into the shadows of an ideology that could no longer survive in the light.