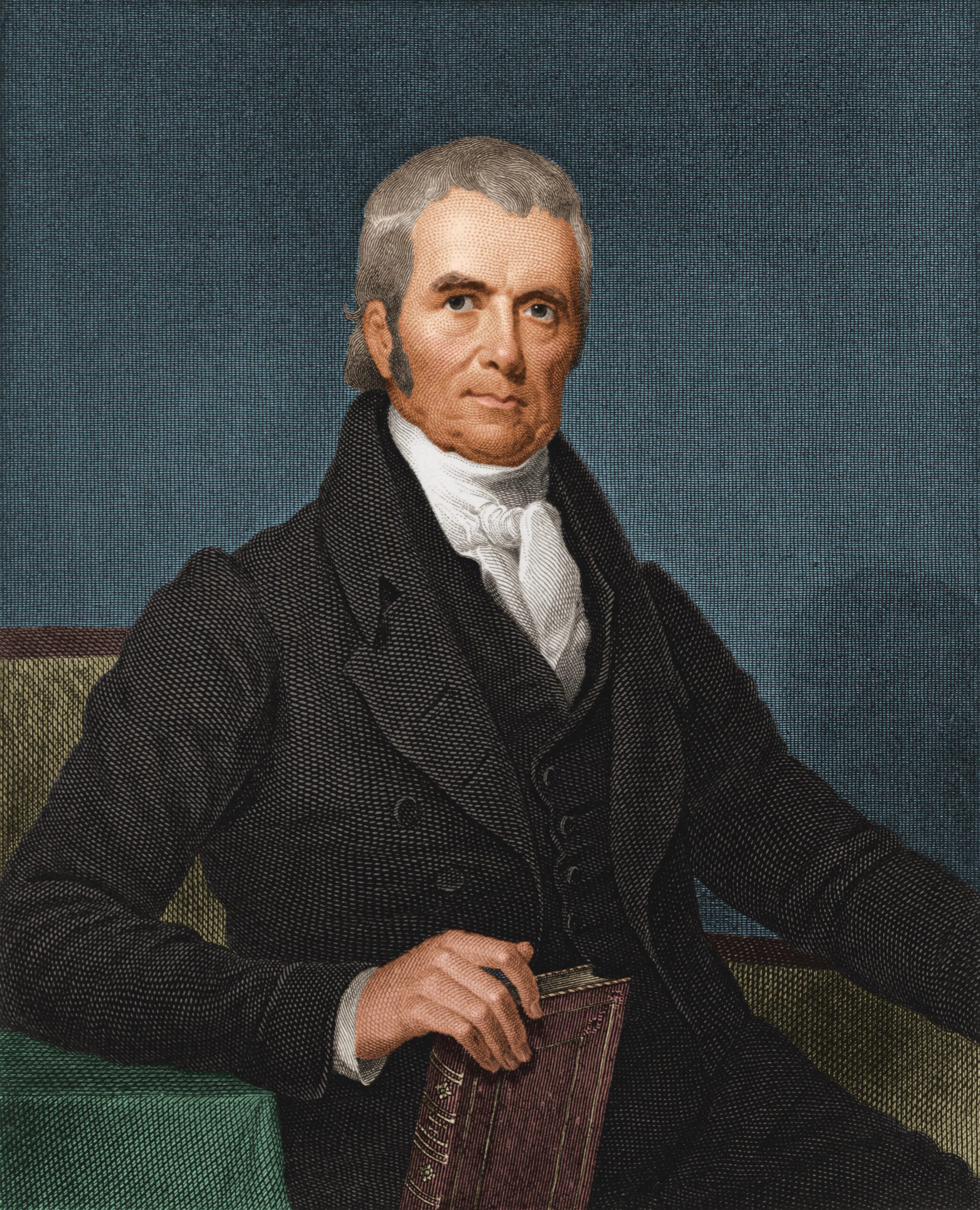

There is a reverence to the way law schools teach Supreme Court history: Precedent is everything, so the writings of early justices are paramount. And although John Jay was the first Chief Justice of the United States, and many other influential justices have since held the position, in law school classrooms, it feels like the Court’s cultural founder is Chief Justice John Marshall—the man whose words, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” elevated the seemingly weakest branch of government to the final authority on what the Constitution means.

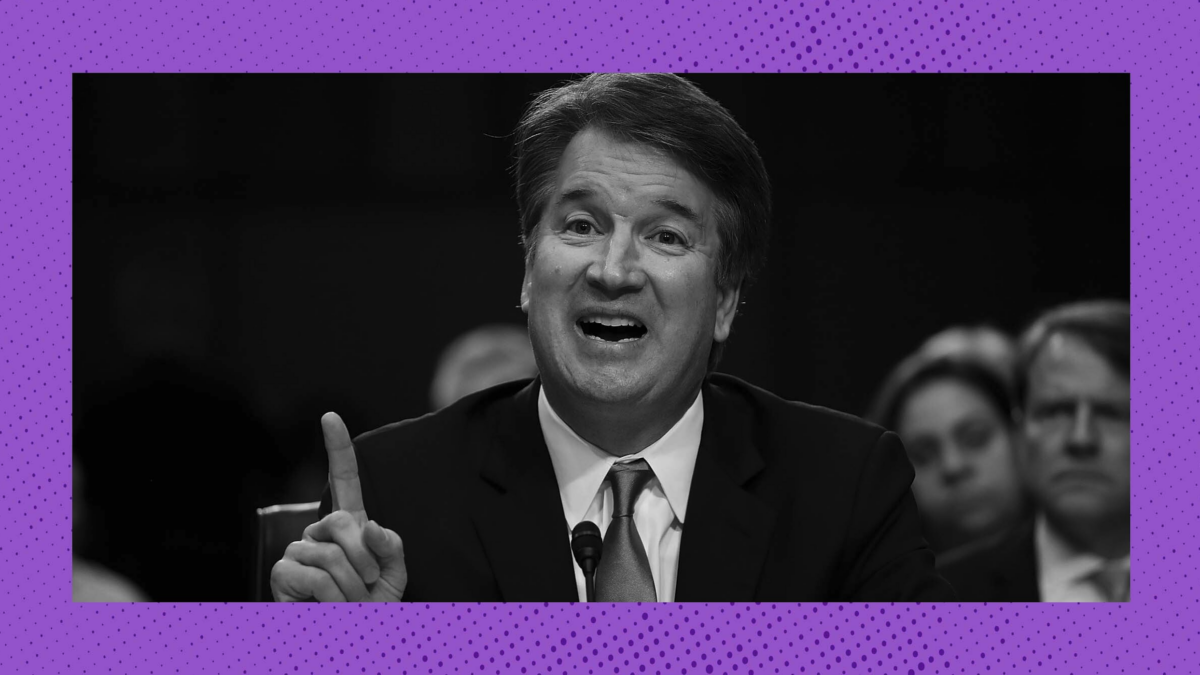

But when you read the substance of Marshall’s opinions rather than memorizing famous quotes, a different picture emerges: a guy who often just said things with so much self-assuredness that no one asked questions. Modern originalists say they detest the notion of judges deciding cases based on the prevailing opinions at the time, but this sort of extra-constitutional assertion was Marshall’s bread and butter—which makes him not that much different from today’s most confident, least competent justice, Brett Kavanaugh.

Take Marbury v. Madison, an 1803 case that is the foundation of judicial review in the United States. During the contentious transition between the John Adams and Thomas Jefferson administrations, Adams, a Federalist, and then-Secretary of State John Marshall—yup, same one—rushed to complete as many lame-duck appointments as possible. When Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, took office, he refused to recognize the appointments for which Marshall, in his role as Adams’s Secretary of State, had failed to deliver the proper paperwork. One of the appointees denied his would-be office, William Marbury, sued to force Jefferson to deliver what he viewed as his rightful commission.

Marshall, who had also been appointed to the Court by Adams and briefly served as both Secretary of State and Chief Justice, saw an opportunity. His opinion in Marbury stated that Jefferson’s decision to withhold Marbury’s commission was illegal, but that the Court could not force him to deliver it, because the Judiciary Act of 1789, a federal law that ostensibly gave the Court jurisdiction over Marbury’s case, was unconstitutional. Marshall thus both gave his political allies a win and made his Court the ultimate authority on the Constitution, with the power to strike down acts of Congress that violated it.

In fairness to law schools, most professors teach this case as both a clever resolution of a political problem, and a savvy power grab by the Court at a time when the country was still trying to find its feet. But they also take Marshall’s conclusion as a given—that the Court has the inherent power to strike down the acts of its co-equal branches. In the centuries since, this power has allowed the Court to address injustices and illegality perpetrated by the government. It has also led to our current system where five (or six) wildly unpopular reactionaries can implement their policy agenda by recasting it as the Constitution’s objectively correct meaning.

What constitutional provision allowed Marshall to draw this conclusion? Beats me! In Marbury, Marshall simply asserted that “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” It is true that there is evidence that some Framers assumed that the power of the judiciary would include judicial review. But in a legal system that ostensibly relies on reasoned decisions and places great weight on the law’s plain meaning, one might expect such a vaunted legal mind to provide at least some kind of citation first.

In the same opinion, to tee up his arguments about the Court’s jurisdiction, Marshall proclaimed that “the government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men.” Marshall’s use of “emphatically” is apparently a tell for when he is stating his opinion—a bit of obfuscation-by-passive-voice that is more or less an old-timey version of “many people are saying.”

Marshall’s vibes-based approach to jurisprudence also runs through early cases about the relationship between the federal government and Native people. In Fletcher v. Peck, a lawyer for one of the parties questioned whether Native people legally owned the land on which they’d lived for generations. In his opinion, Marshall asserted that “Indian title…is certainly to be respected by all courts until it be legitimately extinguished” (emphasis mine). In other words, Marshall decided that, legally, dispossession of the land’s original inhabitants would be fine, so long as Congress said so first.

In 1823, Marshall got a chance to put that attitude into practice in Johnson v. M’Intosh, in which the Court had to resolve conflicting claims to land from a claimant who purchased title from the Piankeshaw, and another who purchased it from the federal government. In his opinion, Marshall frames the case in terms of the Doctrine of Discovery, a synthesis of several papal decrees laying out rules for how Europeans would colonize the Americas. The doctrine has since been repudiated by the Vatican, but Marshall’s reliance on it provided a pretty strong hint about where things were headed: Grants of land, he said, “have been understood by all to convey a title to the grantees, subject only to the Indian right of occupancy.”

Of course, Marshall’s “all” excludes the understanding of Native people. But again, Marshall’s use of this “many people are saying”-style language allowed him to draw his preferred conclusion, which almost certainly just seemed correct to a 19th-century Supreme Court justice: “Conquest gives a title which the courts of the conqueror cannot deny,” he wrote.

Finally, in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Court decided that it lacked jurisdiction over the Cherokee’s lawsuit against Georgia on the grounds that the Cherokee were not a “foreign” nation. Marshall’s opinion described tribes as “domestic dependent nations” with a relationship to the United States analogous to that of “a ward to his guardian”; foreign nations as contemplated by the Constitution, he pointed out, would not refer to the president as the “Great Father.” Setting aside the extensive colonial history leading to this kind of language, the basic fact that this sort of language appeared in treaties—you know, like the kinds that the U.S. makes with foreign nations—did not play a significant role in Marshall’s analysis.

Opinions like these are foundational to early U.S. jurisprudence, but the actual analysis would get laughed out of a 2L moot court competition. Which brings us to Kavanaugh, who recently wrote a concurring opinion in Noem v Vasquez Perdomo, the shadow docket Supreme Court order that blessed federal immigration officials’ use of racial profiling to detain people they suspect of being undocumented. The majority in Vasquez Perdomo did not explain itself, but as the Court faces increasing criticism of its expectation that lower court judges treat its unreasoned orders as binding precedent, Kavanaugh took a stab at making it make sense. It didn’t go well—most notably when, in support of the proposition that “being at Home Depot” is a factor that can give rise to reasonable suspicion of a person’s undocumented status, he cited “common sense.

As dumb as that sounds (and it is), it might be the most honest form of originalism we’ve ever seen, because Kavanaugh instinctively replicates the form and reasoning of early Marshall Court decisions: assumptions in search of authority, conclusions without argument, and outcomes he frames as self-evidently reasonable and correct. When you look at how Marshall and his contemporaries actually decided cases, separate from the sanitized version pitched by Scalia-worshipping law professors, it’s exactly this: a confident declaration dressed in lofty language, justified not by law but by elite consensus. In Fletcher v. Peck, Marshall himself explained that judges know unconstitutionality when “the judge feels a clear and strong conviction” that the law and Constitution are at odds. Today’s Court clearly has a lot of feelings.

The rise of the shadow docket—the Court’s preferred tool for issuing massive rulings with little or no briefing, argument, or explanation—is just the latest manifestation of this intellectual laziness. Not even John Marshall had to justify things he simply knew to be true. If you are a Trump justice looking to approve another aspect of Trump’s agenda, why should the rules for you be any different?