Justice Clarence Thomas’s recent majority opinion in Shinn v. Martinez Ramirez is a grab bag of the worst parts of the Supreme Court’s criminal law jurisprudence. “Respect for finality” of a conviction and death sentence, even with substantial evidence pointing to the defendant’s actual innocence? Check. Handwringing about the prospect of people on death row “sandbagging” the courts with claims of ineffective trial and appellate lawyers? Check. Faulting a prisoner for his attorneys’ mistakes, but forgiving the mistakes of the government’s counsel so as to help speed an execution along? You bet!

The decision also includes the key characteristic of a criminal law opinion from the Court’s conservative wing: a description of the underlying crime with gory details far more familiar to a true crime podcast or a police procedural. (“On May 1, 1994, Barry Lee Jones repeatedly beat his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter, Rachel Gray,” Thomas wrote. “One blow to Rachel’s abdomen ruptured her small intestine.”) Exploiting tragic facts like these provides rhetorical cover for a key conservative policy goal: rolling back defendants’ constitutional rights.

Legal opinions typically begin with an outline of a case’s substantive and procedural history. The descriptions offered in many of these rulings, though, go far beyond what is necessary to understand the legal issues. Consider the case of Matthew Reeves, who was executed by the state of Alabama in January for the 1996 murder of Willie Johnson. The Court’s 2021 opinion, which upheld his sentence over the liberals’ dissent, began, “Willie Johnson towed Matthew Reeves’ broken-down car back to the city after finding Reeves stranded on an Alabama dirt road. In payment for this act of kindness, Reeves murdered Johnson, stole his money, and mocked his dying spasms.”

This issue in this case, however, was not whether Reeves’s crime was despicable. It was. The issue was whether his lawyers erred by failing to call an expert to testify to Reeves’s profound intellectual disability, which could have influenced the decision to sentence him to death. Reeves’s treatment of his victim didn’t make it any more or less constitutional for him to receive ineffective assistance of counsel.

Conservative justices have been doing this for a long time. Thomas presented a similarly graphic fact pattern in United States v. Tsarnaev, as did Justice Neil Gorsuch in Bucklew v. Precythe. For example, discussing eight-year-old Boston Marathon bombing victim Martin Richard, Thomas detailed the way that “BBs, nails, and other metal fragments shot through his abdomen, cutting through his aorta, spinal cord, spleen, liver, pancreas, left kidney, and large intestines.” In Bucklew, Gorsuch describes the defendant, “bearing a pistol in each hand,” shooting his neighbor and pistol-whipping his wife. In Edwards v. Vannoy, decided in 2021, Justice Brett Kavanaugh recounted the defendant’s string of kidnapping, robbery, and rape, and notes that the defendant confessed on tape—the hour-long video of which, he helpfully informed readers, is available to view on the Court’s website.

But Tsarnaev was about jury selection procedures and evidentiary rulings, and Bucklew, method-of-execution challenges. Edwards was a fairly technical case about whether a recently-announced Supreme Court rule regarding jury unanimity applied retroactively. Neither decision turned, in any sense, on just how evil the defendant was. The Court’s vivid language, however, draws the reader’s attention away from the constitutional principle at issue and reassures them that, yes, the state really is executing a Bad Man Who Deserves It.

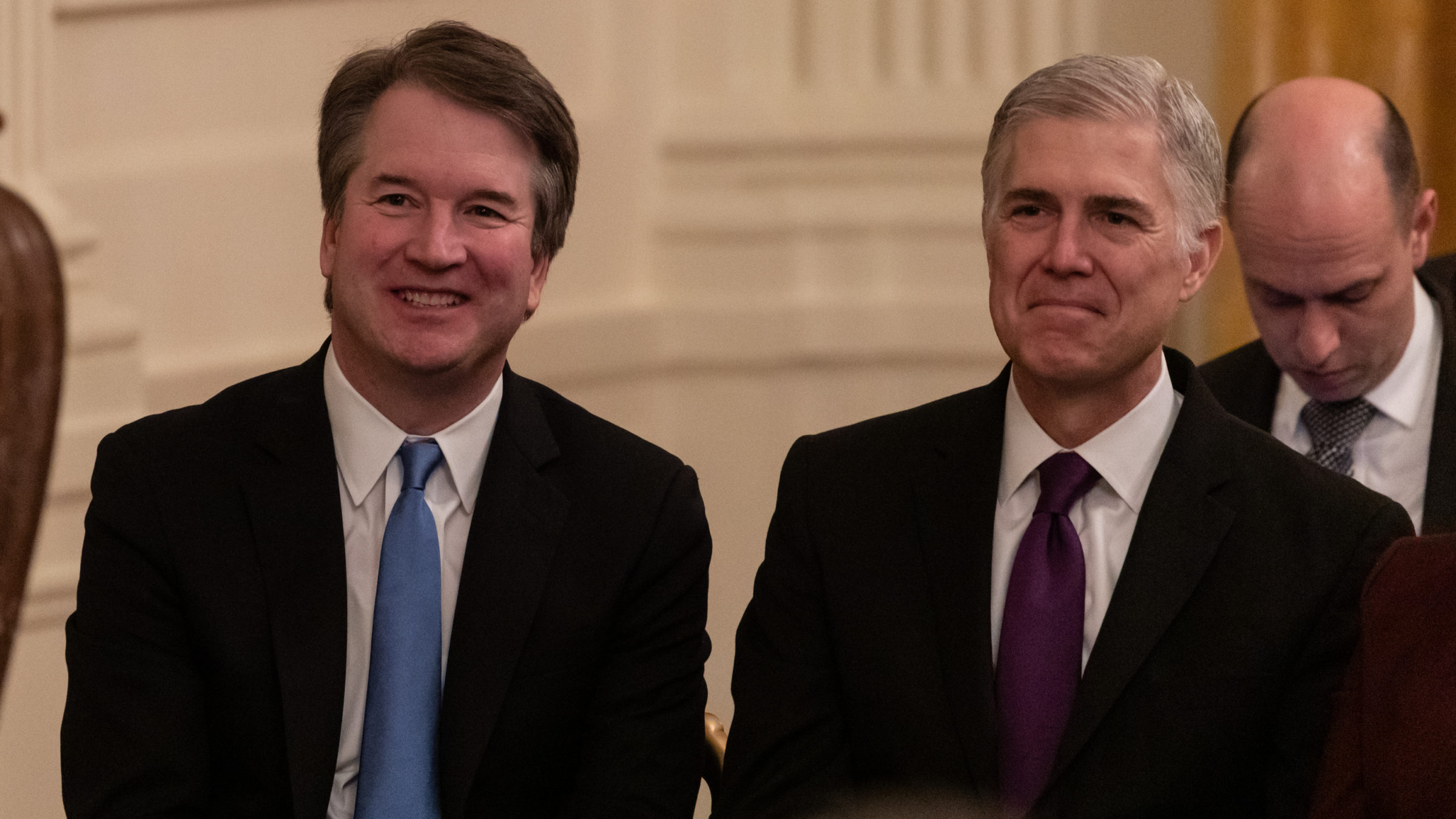

When the newest My Favorite Murder episode drops (Photo by Cheriss May/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

The problem with these horrendous renderings of the underlying crime isn’t that they offend some sense of decorum. Rather, by foregrounding and focusing on the atrocity of the defendant’s actions, the Court’s conservative majority distracts from the atrocity of the state trampling on legal rights in its rush to punish. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor writes in dissent in Martinez Ramirez, “The majority sets forth the gruesome nature of the murders with which respondents were charged. Our Constitution insists, however, that no matter how heinous the crime, any conviction must be secured respecting all constitutional protections.”

Implicit in these opinions is the idea that, by re-centering the case on the gory facts of crime and not the pesky legal details, these justices are honoring the victims. Dissenting in Ramirez v. Collier, one of the few pro-defendant death penalty rulings from the Court, Thomas opined that “by evading his sentence, Ramirez has inflicted recurrent emotional injuries on the victims of his crime.” This followed a gruesome rendition of Ramirez’s murder of Pablo Castro, which, Thomas, said “warrants a fuller retelling than the majority provides.” Thomas suggests that recounting Ramirez’s offense in detail honors Castro, and offers Castro’s suffering as a reason to reject Ramirez’s unrelated claims.

This reasoning doesn’t advance victims’ interests. On the contrary, this rhetoric demeans victims by co-opting them for the conservative wing’s desired policy agenda: to make executing people an altogether easier task. The “evasion” of Ramirez’s death sentence that upset Thomas so much? Ramirez wished, in accordance with his First Amendment rights, that a chaplain pray over him as Texas killed him.

This proclivity for true-crime-esque detail taps into a deeper cultural trend. As Emma Berquist has persuasively argued in Gawker, the true crime podcast craze has warped Americans’ sense of risk and sparked a reactionary disdain for constitutional safeguards among conservatives and liberals alike. Police procedurals, too, inflate both the perception of crime and also the broader social tolerance for civil rights violations committed in the name of arresting, charging, and convicting someone as quickly as possible. If the person they’ve found is guilty of a horrendous act, what do a few cut corners matter?

This unconscionable disinterest in constitutional rights has devastating consequences. Constitutional guarantees, of course, do not hinge on one’s guilt or innocence. But even innocent people can pay a price for the legal system’s failures: An estimated 54 percent of wrongful convictions result from government misconduct, and Black Americans wrongfully convicted for murder are likelier to have been victims of misconduct than similarly-situated white Americans. Grisly Supreme Court opinions and rampant police and prosecutorial misconduct are symptoms of the same pathology: thinking that a particularly bad crime creates a Constitution-free zone.

True crime and crime dramas paint a stark picture of the world: Evil lurks around every corner, and the criminal legal system must protect the good from the bad. But the Constitution applies to everyone. Ernesto Miranda, for whom the famous “you have the right to remain silent” police warning is named, kidnapped and raped a woman. John Leo Brady, whose Supreme Court case requires prosecutors to turn over exculpatory evidence to the defense, helped murder a man. The Constitution protected them, and it protects us all in part because of them, too.

When the Court’s conservatives treat death penalty litigation as evasion and subordinate finality to justice, they treat the Constitution like the pesky TV police captain that stops the dedicated detective from cracking a few skulls to solve the case—just one more inconvenience jamming up the machinery of death.