Judge James Ho has made a name for himself as the MAGA darling of the federal courts, waging war on “cancel culture” and frequently issuing unhinged opinions (and speeches at Federalist Society events) taking aim at “cultural elites.” In September, Ho, who was appointed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals by President Donald Trump in 2017, announced a boycott on hiring clerks from Yale Law School until it changes its “closed and intolerant environment.”

Ho’s objections do not stem from, for example, Yale’s historical ties to slavery or its reputation for fostering a misogynistic environment. No, Ho is concerned about the Yale Federalist Society’s ability to invite hate groups to speak at the law school without backlash. “When elite institutions make clear that people who think like you and me shouldn’t even exist, we return the favor,” he said at a Federalist Society conference in Kentucky last month.

This story begins in March, when about 100 Yale Law School students briefly protested and walked out of a talk featuring a representative from the Alliance Defending Freedom, which the Southern Poverty Law Center has designated as a hate group for its work promoting the criminalization of homosexuality, bans on gender-affirming care for trans folks, and other attacks on LGBTQ rights. Shortly after an outcry from conservative media, Yale Law updated its freedom of speech and disciplinary policies to make disruptions of events academic offenses, and to ban unauthorized recording. Any protest that “obstructs the view of those attempting to watch an event”—for any amount of time, apparently—could qualify as a violation. Students protesting a similar event in the future, even with a completely silent walk-out, risk drawing a complaint from FedSoc weenies and a note on their permanent records.

These concessions were not enough for Ho, who moved forward with his boycott, cheered on by conservative commentators. (Some went so far as to call for a boycott of Yale graduates by future Republican presidential administrations, too). Now, after “quietly reaching out” to unspecified conservative judges, Yale Law administrators are trying to appease him, offering Ho and fellow boycotter Judge Lisa Branch the opportunity to speak and address the issue of “free speech on campus.” The event is tentatively scheduled for January 17, 2023, but Ho and Branch have urged Yale to host them earlier.

This strategy of appeasement is misguided. Conservatives will never stop complaining about cancel culture at elite universities where, despite having a fast track to the judiciary for their fellow travelers in the Federalist Society, they see student organizing as an attack on their outsized influence on legal and public discourse. As cowardly as Yale’s response was, it is emblematic of elite law schools’ focus on building relationships to established power, rather than on pursuing justice.

Whenever law schools are faced with any degree of dissent from students, the playbook goes something like this: Students express their displeasure with a speaker at the school or with another administrative decision; in response, the school invites the speaker to address the issue in a closed session with no recording or note-taking allowed; and the students are ultimately upbraided by the administration to the satisfaction of the speaker. Even David Lat’s sympathetic coverage of the controversy points out that anything less than a fully submissive response from the Yale Law student body is unlikely to appease the judges or the conservative legal establishment cheering for the boycott.

By functionally demanding that students debase themselves by taking him seriously, Ho has guaranteed his frontrunner status next time a Supreme Court vacancy opens up under a Republican president. The cancel culture grift bears too much fruit for people like Ho to actually consider giving it up.

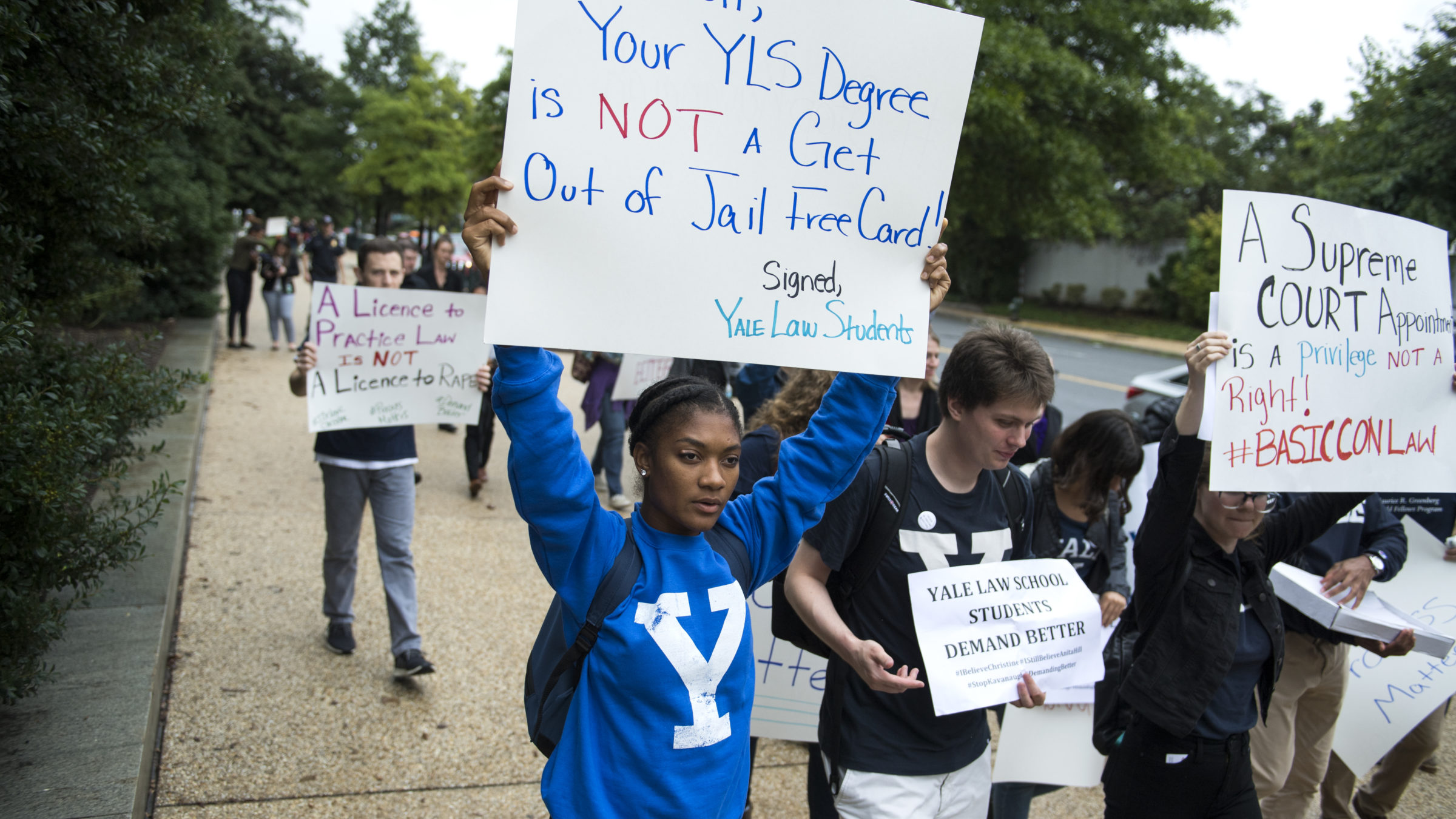

Yale Law students protest the Supreme Court nomination of Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, a sight which James Ho finds deeply offensive (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call)

Beyond squashing the free speech rights of its students, Yale’s bowing and scraping before influential judges reinforces one of the more toxic hidden messages of legal education: Power is paramount. Students are explicitly taught to leave ideas of fairness and justice behind in order to “think like a lawyer,” which ultimately means upholding the status quo. Doctrinal classes like contracts and torts, which are based on centuries-old common law principles, are students’ first introduction to the law, and specifically instruct students not to consider policy or fairness, but only precedent. Students who spend time on experiential learning and pro bono work rather than prestigious doctrinal classes are known as “clinic rats,” and clinical professors are seen as being of lower status than others on the faculty. And of course, large law firms dominate law school career offices and hold highly-publicized recruiting events early and often, driving students toward big-money jobs that boost schools’ rankings and bring in financial support. Prestige and money are the currencies of law school—justice is secondary.

But imagine if Yale had decided to take a stand. A handful of ultraconservative judges passing on hiring Yale students as clerks would hardly make the top-ranked law school in the country less attractive or prestigious overnight. The administration could have acknowledged its students’ rights to free expression, and the importance of that expression from the next generation of the legal profession. Instead, it told its students to keep their mouths shut.

Since the administration refused to stand up for its students, it is up to the students themselves to take action. Protests at Yale and elsewhere are part of a growing effort to fight corporate domination on campus and the laundering of discriminatory policies through “neutral” legal debate.

For example, organizations like People’s Parity Project, of which I am the Organizing and Network Director, and Law Students for Climate Accountability have taken a community organizing approach to pushing back on the risk-averse culture of many law school campuses. Students at Harvard Law recently called on the administration to add classes and clinics on reproductive rights in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, drawing support from the Cambridge City Council. Others have been lobbying for improvements to public interest loan repayment programs, and organizing boycotts of firms that oppose workers’ rights or work with companies driving the climate crisis. Still more are pushing for greater protections for sexual assault survivors on campus, and to ensure that accused sexual predators are not invited to teach at their schools.

That this swell of law student activism has generated a strong institutional response speaks to the power that students have when they act together. Students pushing law schools to serve justice see the legal profession as a force for progressive change, and expect their schools to follow suit. When announcing his boycott, Ho stated that judges are law schools’ customers and can influence them through a boycott. He is wrong. The student is the customer, and law schools are nothing without them. It is a hopeful sign for the profession that students are starting to realize that.