This month’s chaotic Supreme Court arguments on the Biden administration’s workplace COVID-19 vaccination rules were typical of this 6-3 conservative supermajority: the usual mix of overlong hypotheticals, ahistorical musings, and overt hostility to the executive branch. But one brief comment from Justice Brett Kavanaugh also revealed much about the stories attorneys and judges tell themselves about the role and status of “law” as privileged above everything else.

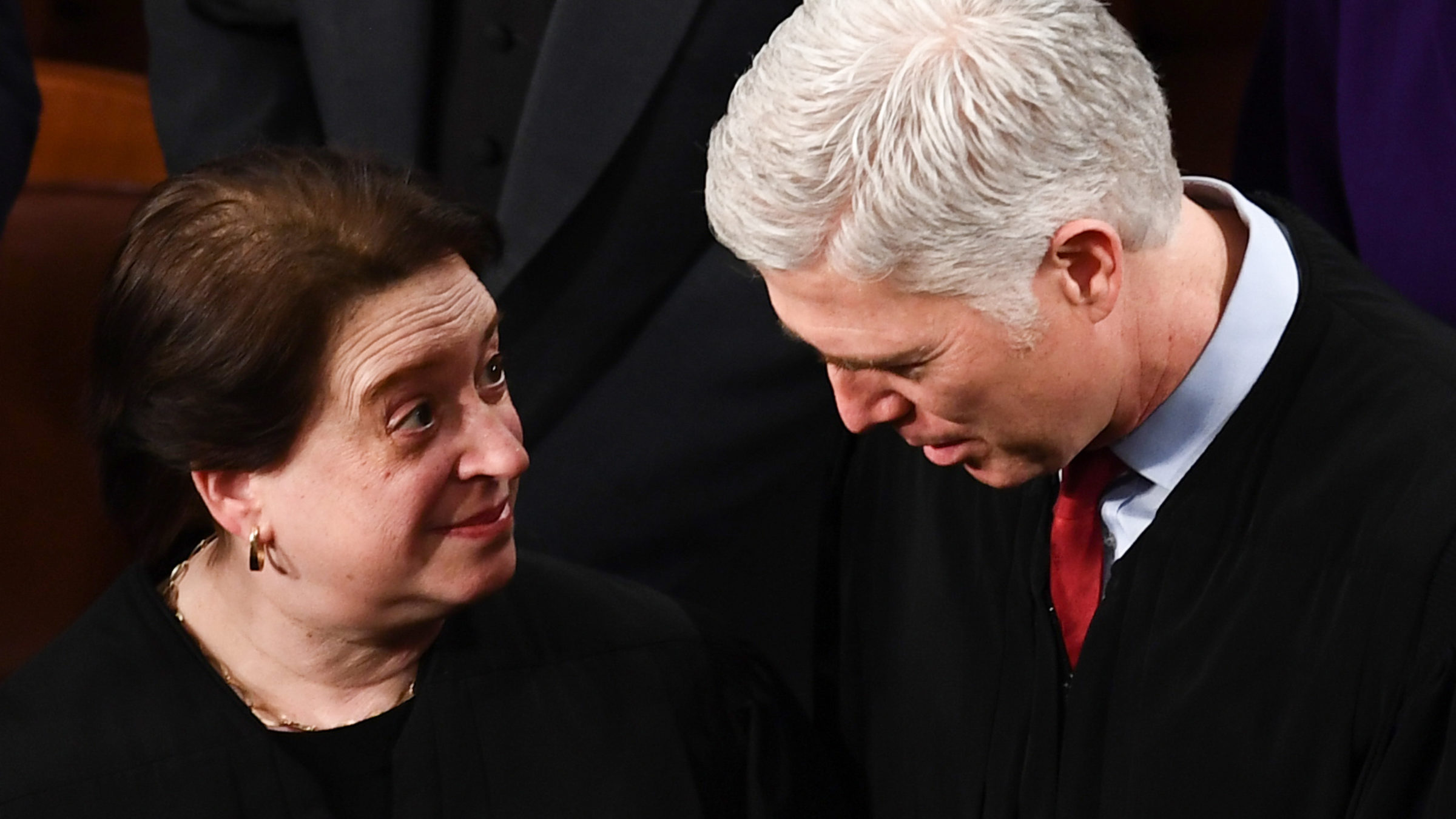

Kavanaugh spoke after Justices Elena Kagan and Neil Gorsuch, who had just asked questions about the scope of administrative law and the slippery “major questions” doctrine, respectively. “I want to follow up on Justice Gorsuch’s questions, which I think are important, and also Justice Kagan’s questions about the policy arguments that are present here,” Kavanaugh mused. His comment tellingly blessed Gorsuch’s “important” legal questions over Kagan’s mere inquiries into “policy” (while ignoring that both justices were actually asking similar questions).

This sounds all too familiar to those of us who’ve survived the law school experience, in which faculty and peers may dismiss some students’ perfectly valid points as mere “policy arguments.” For law students, the answer to a “cold-call” of the type seen in Legally Blonde “should” be grounded in the case or statute at issue rather than larger concerns like justice, morals, or equality. Students learn fast that, if you care about the equity goals of the Voting Rights Act or the repercussions of artificially cramped standing doctrine, you better have something more than “policy” to justify your arguments.

Many lawyers, law professors, and judges treat policy as basically just vibes: emotions and feelings dressed up in rhetoric. Law, by contrast, is Solid, Determinate, and Consistent: an elegant edifice, chiseled and crafted by all-knowing judges and learned attorneys. There might be harsh results or perverse incentives, sure, but that’s the price to pay for stability. Indeed, a lack of concern for squishy values like “justice” proves the higher meaning and value of law—there’s no room for maneuvering.

There are (at least) two problems with this view. First, it creates an artificial distinction between law and policy, casting them as disparate arenas rather than inextricably intertwined. Second and more insidiously, it creates a hierarchy in which law reigns supreme over subjective and “imprecise” disciplines like policy, which can too closely resemble feelings in its concern for non-legal considerations. When lawyers and judges assert that law trumps other concerns, they implicitly subordinate those who claim allegiance to other values or disciplines. You’re either on our team, or you’re a loser.

Just two policy experts, chopping it up (Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

Perhaps because I was told during my first year of law school that my questions were actually “policy inquiries,” I enrolled in a policy program and graduated with a joint degree. There, I learned that policy is more than vibes. It’s a set of social considerations and goals partially achieved through law, informed by empirical and qualitative research and a range of academic disciplines. The best policy scholars and policymakers craft their views with more rigor than one finds in judicial opinions, and with more collective, distributed input. Yet prominent judges seem to both disdain policy and collapse disciplines like sociology, statistics, and economics into a mess they characterize as simultaneously finicky and mushy.

Take our Chief Justice, for example. Who can forget John Roberts describing sophisticated statistics during oral argument in Gill v. Whitford, a 2017 challenge to partisan gerrymandering, as “sociological gobbledygook”? That facile insult prompted the then-head of the American Sociological Association to write him a letter reminding him that Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision that declared school segregation unconstitutional, relied on psychological and sociological evidence to demonstrate why separate wasn’t equal. (Of course, given contemporary conservative hostility to Brown v. Board—I’ve lost count of how many Trump judicial nominees refused to say it was rightfully decided during their confirmation hearings—for some judges, citing it to show that sociology matters for law might be a turnoff.)

More recently, at oral argument in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health—the case from this term that the conservative justices will likely use to hollow out legal protections for reproductive rights—Roberts again signaled that data and policy analysis, no matter how expert or sophisticated, has little to commend it. This seems especially true when “policy” might stop the Court’s right wing from fulfilling its mission of eliminating bodily autonomy for those who can become pregnant. When Julie Rikelman, the lawyer for the Center for Reproductive Rights arguing the case, noted that in the nearly fifty years since Roe v. Wade, “abortion has been critical to women’s equal participation in society,” Roberts asked for the data. After Rikelman cited an impressive amicus brief filed by over 150 economists and researchers proving her point, Roberts breezily ignored it. “Putting that data aside,” he said, he quickly moved on to more serious, more “legal” inquiries: why upholding Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban wouldn’t present a major shift from the existing viability standard. Rather than examining careful non-legal scholarship, tired, formalist legal questions about line-drawing maintained superiority.

It would be one thing if the justices’ contempt for policy were accompanied by a principled distinction between law and policy. But no serious reader of the Supreme Court’s recent opinions could ignore the policy goals that dominate. In Brnovich v. DNC, a 2021 decision that eviscerated whatever remained of the Voting Rights Act, Justice Samuel Alito decided that he would rewrite the statute to further Court’s policy agenda of eliminating the VRA’s protections for minority voters. Conservative justices often extoll the primacy of statutory text—but not, it seems, when more important social goals of the conservative legal movement are within striking distance.

When you ask for “data” but then someone actually provides it and you don’t care for the answer (Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

Or consider Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, another case decided in 2021 along ideological lines. Two non-profit entities (one associated with the Koch brothers, the other a law firm that “defends and promotes America’s Judeo-Christian heritage and moral values”) successfully argued that a hypothetical injury—that California’s mandated financial contribution disclosures somehow chilled their First Amendment speech rights—was sufficient to confer standing. Standing requires that plaintiffs in federal cases demonstrate that they’ve suffered a concrete, particularized injury. In Bonta, the Court decided that these nonprofits who had suffered no such injury could nonetheless challenge California’s law.

Most of the time, judges use standing doctrine to keep out those claimants who’ve been injured in ways that judges might not care much about, like privacy or civil rights. Indeed, in a consumer rights case the Supreme Court decided just one week prior to AFP, Kavanaugh had written an opinion sharply limiting Congress’s power to create standing. But when it comes to funding conservative political causes, that hostility to finding standing was nowhere to be found.

My skepticism about a principled divide between law and policy dates back to 1L. In Constitutional Law we debated the then three-month old decision in D.C. v. Heller, which overturned decades of precedent in finding an individual Second Amendment right, to gun ownership. In the majority and dissenting opinions Justices Scalia and Stevens, respectively, spend way too much time arguing about competing dictionary definitions. Justice Scalia, citing to multiple dictionaries: “At the time of the founding, as now, to ‘bear’ meant to ‘carry.’” Justice Stevens, citing to others: “One 18th-century dictionary defined ‘arms’ as ‘[w]eapons of offence, or armour of defence.’”

This is what legal analysis is? I remember thinking. Arguing over what dictionary applies? I thought that taking your intuitions about the Second Amendment’s original meaning and slapping on a veneer of objectivity using Samuel Johnson’s dictionary was exactly the kind of extra-legal thinking we were supposed to eschew. Apparently not.

There’s more at stake here than rhetorical consistency. Judges’ vocal disdain for policy means they can have their cake and eat it too: relying upon the image of law as precise and implacable while setting priorities as they see fit. Courts making policy choices while denigrating policy analysis are like the Very Successful Person who tells you America’s a meritocracy where they pulled themselves up by their bootstraps—and somehow forgets to mention their trust fund.

Policy and law are inextricable. Lawyers need to understand policy and what we can learn from our colleagues in other disciplines. As an instructor, I encourage my students to consider the policy arguments supporting the rules and laws that legislatures, agencies, and courts propound, and the sources for those arguments. If the last few years have proven anything, it’s that lawyers and judges need to have more humility about the limits of law, particularly when other disciplines can provide more insight to why the world is so broken—and what it would take to fix it.