Late last week, the Trump White House dropped yet another unconstitutional executive order that threatens whatever remains of the rule of law. But rather than once again targeting one of his old standbys—immigrants, trans people, Black people—this time Trump chose the law firm of Perkins Coie. In a belated response to Perkins’ representation of the Democratic Party during the 2016 election cycle, Trump has suspended security clearances for Perkins lawyers, limited their access to government buildings, and prevented government agencies and contractors from doing business with the firm. This bullying tactic follows a related order Trump issued late last month against Covington & Burling, which represents former special counsel Jack Smith.

Anyone wondering whether law firms might face similar threats or actions didn’t have long to find out. In an interview on Sunday morning, Trump suggested to Maria Bartiromo of Fox News that he isn’t done yet. “We have a lot of law firms that we’re going to be going after, because they were very dishonest people,” he said. “It was so bad for our country.”

Both Perkins and Covington have substantial resources and social power, so perhaps one might assume they can easily resist these actions. But even if a court strikes down these orders, Trump’s actions demonstrate once again the glee with which he and his entourage have marched us all down the road to authoritarianism.

Any reasonably experienced White House lawyer would know that these executive orders have constitutional defects. But of course that’s besides the point; the government, as usual these days, seeks to intimidate any meaningful opposition. Threatening lawyers and legal organizations remains a classic from the despot’s playbook. Letting these orders stand without robust opposition—such as lawsuits from the affected firms, media statements from their leaders, and advocacy from similarly situated law firms—merely makes it easier for this administration to continue to stomp on less prominent targets.

The orders themselves fail constitutional scrutiny. The First Amendment protects people from retaliation for exercising their free speech rights, and both firms have strong arguments to employ against Trump’s actions. Just last term in National Rifle Association v. Vullo, a unanimous Supreme Court reaffirmed a sixty-year old holding that government officials “cannot attempt to coerce private parties in order to punish or suppress views that the government disfavors.” Three years ago, the Court unanimously reiterated in Houston Community College System v. Wilson that “the First Amendment prohibits government officials from subjecting individuals to ‘retaliatory actions’ after the fact for having engaged in protected speech.”

These holdings give the law firms’ potential First Amendment claims real teeth. In both executive orders, the White House explicitly referenced the work Covington and Perkins did on behalf of specific clients. In 1963, the Supreme Court decided NAACP v. Button, a case in which the NAACP challenged Virginia’s regulation of its legal work as an infringement on its First Amendment rights. Justice William Brennan, penning Button’s majority opinion, observed the First Amendment not only protects corporations, but also “vigorous advocacy, certainly of lawful ends, against governmental intrusion.”

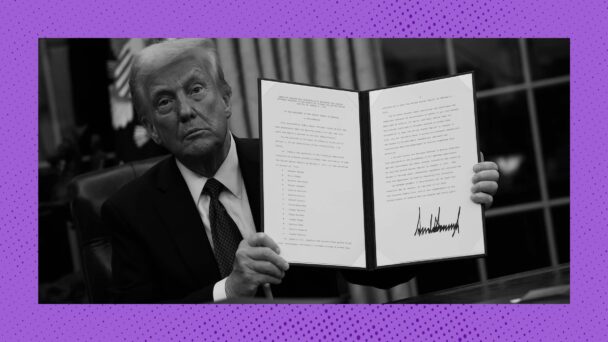

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

By targeting lawyers and law firms for their advocacy against Trump’s enemies, the White House mimics its favorite authoritarian regimes abroad, in which despotic leaders intimidate, threaten, and even injure or kill lawyers who resist. Consider the Philippines, where over sixty lawyers were murdered during the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte between 2016 and 2022. Duterte notoriously carried a list of those whom he claimed were protecting drug suspects; he had told the police, referring to lawyers, “If they are obstructing justice, you shoot them.” A decade ago, Chinese authorities engaged in a sweep to arrest human rights lawyers and activists whom the government resented for their advocacy on behalf of political dissidents and religious minorities. The Chinese government prosecuted many of those lawyers, arguing in some cases that the human rights lawyers were maligning the legal system, and coordinating with foreign groups to spread methods of resistance against the state.

Targeting lawyers who represent government critics allows the state to intimidate both legal experts and enemies of the state simultaneously. If activists don’t have meaningful legal representation, they will either stay quiet or suffer reprisal. Having a lawyer doesn’t ensure that a dissident will remain free to speak and work, but the presence of a lawyer can support both legal and non-legal advocacy. That’s precisely why some authoritarian regimes target the legal profession—their leaders understand that lawyers can serve as a powerful fulcrum in social movements.

The new administration has not acted as brazenly as the Chinese government or Duterte did, but its motivations sound in a similar key. Without strenuous pushback against these executive orders from civil society—from the targeted firms, from their competitors, and from scholars and advocates focused on preserving the rule of law—the door to more egregious conduct from the government remains open.

Keeping your head down, as some firms hope to do by keeping silent in the face of attacks on the profession, will not work; as Trump’s comments to Bartiromo impugning firms beyond Perkins and Covington demonstrate, the approach the administration has embraced lacks any limiting principle. And other legal entities—smaller firms, advocacy organizations, and law schools—could come under fire from the administration soon.

Some already have: Attorney General Pam Bondi has called upon the ABA to suspend some of its law school accreditation rules promoting DEI. Ed Martin, the acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, wrote a sniveling letter to Georgetown Law threatening to block any hiring of Georgetown Law students until the school eliminated its DEI programs. In a sadly rare full-throated response, Georgetown Law Dean William Treanor efficiently dispensed with Martin’s pablum, correctly noting that threatening the school violated its First Amendment protections and its missions as a Catholic and Jesuit institution, challenging “Georgetown’s ability to define our mission as an educational institution.”

The public will need many more lawyers, law firms, and legal organizations to echo Georgetown’s response to the unconstitutional threats and bullying that this administration has embraced as its modus operandi. Perkins has hired Williams & Connolly to challenge the executive order; Covington should also file suit. The ABA should tell the Justice Department that its claim about DEI rules has no grounding in law, and every law school dean should reiterate their commitment to core institutional values of inclusion and antidiscrimination. And every AmLaw 100 firm should join a joint statement criticizing the Trump Administration for its brazen attempts to interfere with the practice of law. Strongly worded letters from well-credentialed lawyers will not stop creeping autocracy. But they will at least put a stake in the ground for the democratic values we should promote as a profession.

Lawyers often joke about the famous line from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 2: “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” But that joke’s context explains what Shakespeare meant; as John Paul Stevens noted in a 1985 dissent, “Shakespeare insightfully realized that disposing of lawyers is a step in the direction of a totalitarian form of government.” The threats against law firms and legal institutions mark merely the initial steps along that path.