The primary responsibility of America’s largest law firms is ensuring that the rich and powerful remain rich and powerful. They are handsomely compensated for their trouble. Last year, for instance, the 100 largest law firms by revenue grossed roughly $160 billion altogether.

Although they’re chiefly concerned with the interests of corporations and banks, BigLaw firms also love to tout their pro bono practices, especially when pitching themselves to prospective junior associates at law school job fairs. “Pro bono” comes from a Latin phrase meaning “for the public good.” And when BigLaw firms say they do pro bono, they mean they provide free legal services to people who can’t otherwise afford them, for the benefit of the public.

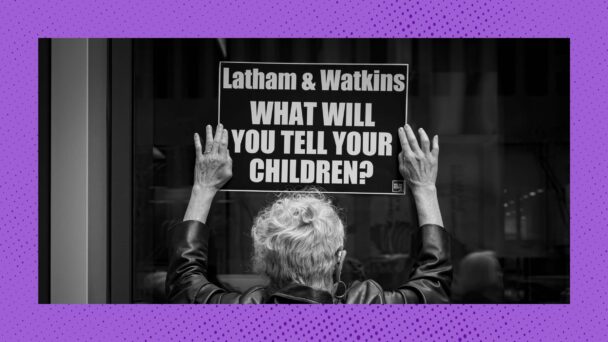

Or at least, they used to. Because the benefit of the public and the benefit of the Trump administration do not tend to intersect, President Donald Trump has used the powers of his office to bully BigLaw out of taking on pro bono cases that could undermine his agenda. Recent reporting shows his intimidation campaign is working: Many BigLaw firms are trying to appease Trump by refusing to help people whose rights are violated by the federal government.

Between February and April 2025, Trump issued several executive orders designed to suppress legal opposition to his policies. Some are broadly applicable, such as the memorandum directing Attorney General Pam Bondi to seek sanctions against attorneys and firms who “engage in frivolous, unreasonable, and vexatious litigations against the United States.” But other orders specifically targeted BigLaw firms by name, and imposed a barrage of punitive measures including the termination of government contracts with firm clients—a clear signal that anyone in the firms’ orbit must leave, lest they face financial consequences, too.

Many of these orders explicitly linked the firms’ punishments to their pro bono representation of clients Trump doesn’t like. The order affecting WilmerHale, for example, claimed that the firm had “abused its pro bono practice” in order to further “the degradation of the quality of American elections” and obstruct “efforts to prevent illegal aliens from committing horrific crimes.” WilmerHale’s recent pro bono representations include successful challenges to racially discriminatory electoral maps under the Voting Rights Act, and to the detention and deportation of certain noncitizens who are actively pursuing lawful immigration status.

As the White House tells it, BigLaw firms use pro bono as a vehicle to “undermine justice and the interests of the United States”; at a press conference in March, Trump said that law firms “have to behave themselves.” By this, he means that meaningful pro bono is an obstacle to tyranny, and that BigLaw firms have to clear a path for him or else. The few firms who have challenged these orders in court have won. But many firms are still wary of retribution, and so they are refashioning their pro bono practices to address the wants of the president, not the needs of the public.

Last week, for instance, ProPublica reported that nonprofits are struggling to find BigLaw firms willing to lend their vast resources to challenge the president’s attacks on vulnerable people. “There are cases that aren’t being brought at a time when civil rights abuses are maybe at the highest they’ve been in modern times,” said Lauren Bonds, Director of the National Police Accountability Project. One BigLaw partner told ProPublica that any cause or client that “this administration and Trump might notice and get angry about” has become “radioactive.”

The week before that, a Reuters investigation found that 17 of the 50 top-grossing firms have revised the descriptions of their pro bono work on their websites to remove mentions of issues like racial justice and immigration. And these changes in wording reflect real changes in actions: Reuters heard from 14 civil rights groups that firms that once proudly did pro bono work with them are now only willing to help in secret—or not willing to help at all. One organization described contacting firms that previously challenged Trump’s immigration policies, hoping to marshal free legal support for people ensnared in recent raids. This time, all declined.

Perhaps more disturbing still, Trump’s neutralization of pro bono goes beyond preventing BigLaw from working against him. He is conscripting BigLaw to work for him, too. In response to his spate of executive orders, to date, nine firms have entered “agreements” that commit a total of nearly a billion dollars’ worth of free legal services to Trump-approved causes. An April executive order hints at one way the White House intends to put BigLaw to use: by providing free representation to law enforcement officers accused of violating people’s rights.

Conservative activists, too, are eager to get in on the action: A few months ago, for instance, a conservative advocacy group sent letters to dozens of BigLaw firms seeking millions of dollars in free assistance in their attacks on voting rights and integration. When some firms hesitated or declined, the organization president told Reuters, “I don’t think the president is going to be happy when he hears law firms aren’t abiding by the terms of these deals.”

Pro bono was the only part of BigLaw not squarely dedicated to enhancing corporate power. Firms that surrender their pro bono practices to the Trump administration are surrendering both the rights of people who counted on them, and the pretense that the firm ever cared.