Call it the Law of Cursed NextDoor Threads: Up and down the West Coast, the larger and wealthier the city, the more upset people are about their local homelessness crisis. Of the roughly 650,000 unhoused Americans at last count, more than a third lived in just three states: Washington, Oregon, and California. California, which by some estimates boasts the world’s fourth-largest economy, is home to more than 180,000 unhoused people. About 15,000 of them are children.

As grim as these numbers are, the spike in handwringing op-eds about homelessness in recent years is mostly a consequence of the fact that the people who write handwringing op-eds about homelessness have to see more of it, more often. Although the number of unhoused people is only (“only”) up 19 percent since 2016, the number of unsheltered unhoused people—people living in cars, abandoned buildings, sidewalk tents, and so on—is up 45 percent over the same period. Close to half of all unsheltered Americans live in California, and mostly in urban areas: About three in four unhoused people in Los Angeles, the East Bay, and Sacramento spend their nights in places not meant for human habitation.

Tents near San Francisco City Hall, May 2020 (Photo by Liu Guanguan/China News Service via Getty Images)

About a decade ago, local officials began responding by passing a slew of “anti-camping” ordinances, many of which imposed criminal penalties on people caught sleeping in public. Sometimes, mere possession of a blanket or pillow in a public park is enough to trigger an arrest; a law in Portland allowed cops to arrest, fine, and even jail people who, for example, are caught more than once using a gas heater to stay warm at night. There is perhaps nothing more American than a city choosing to shelter its poorest residents by locking them inside a cell.

In 2018, however, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held in Martin v. Boise that unless cities provide enough shelter beds to keep everyone safe, warm, and dry, anti-camping bans constitute “cruel and unusual punishment” under the Eighth Amendment. In 2022, a three-judge Ninth Circuit panel relied on Martin to block an anti-camping law in Grants Pass, Oregon, a city of about 38,000 people. The city appealed to the full Ninth Circuit, which declined to take up the case over five dissenting opinions laced with varying levels of NIMBY outrage. Reagan appointee Diarmuid O’Scanlainn, for example, accused the majority of “seizing policymaking authority that our federal system of government leaves to the democratic process.”

The city of Grants Pass, equally incensed, asked the Supreme Court to intervene and get rid of Martin altogether. On January 12, the justices agreed to take up the case, Grants Pass v. Johnson, to settle the constitutionality of public camping bans once and for all. Oral argument is expected in late spring or early next fall.

Leading the fight to overturn Martin are cities and states led by the sort of Democratic politicians who are liberal when it comes to firing off defiant tweets at Donald Trump, but not when it comes to ensuring that their constituents don’t die of exposure. Among them are California Governor Gavin Newsom, the cities of Los Angeles, Phoenix, and San Francisco, and several smaller organizations of cities and counties on the West Coast. In an amicus brief, Newsom purports not to “take issue” with the basic premise of Martin, but bemoans that courts have expanded its protections in “troubling and uncertain ways” that make it harder to enforce “common-sense” anti-camping laws. “Courts are not well-suited to micromanage such nuanced policy issues based on ill-defined rules,” he writes.

To an extent, Newsom has a point: The judiciary is a blunt instrument best equipped to veto policies set by other branches of government, which is, of course, why conservatives have worked so hard to capture it. But America’s homelessness crisis is a policy choice that people like him have made—the product of a cascading series of failures of governance, at multiple levels, over decades or even generations. A recent study found that 9 in ten homeless adults in California became homeless while living in California, primarily because they could not find an affordable place to live. Meanwhile, in its amicus brief, San Francisco tells the justices that they spent $672 million last year to shelter the city’s homeless residents. This sounds nice, until you remember that the city is also spending some $762 million on the police department responsible for arresting them for the crime of being poor in public.

A NYPD officer speaks to a homeless man in the East Village before his tent and belongings were cleared out by the sanitation department, April 2022 (Photo by Bryan R. Smith / AFP)

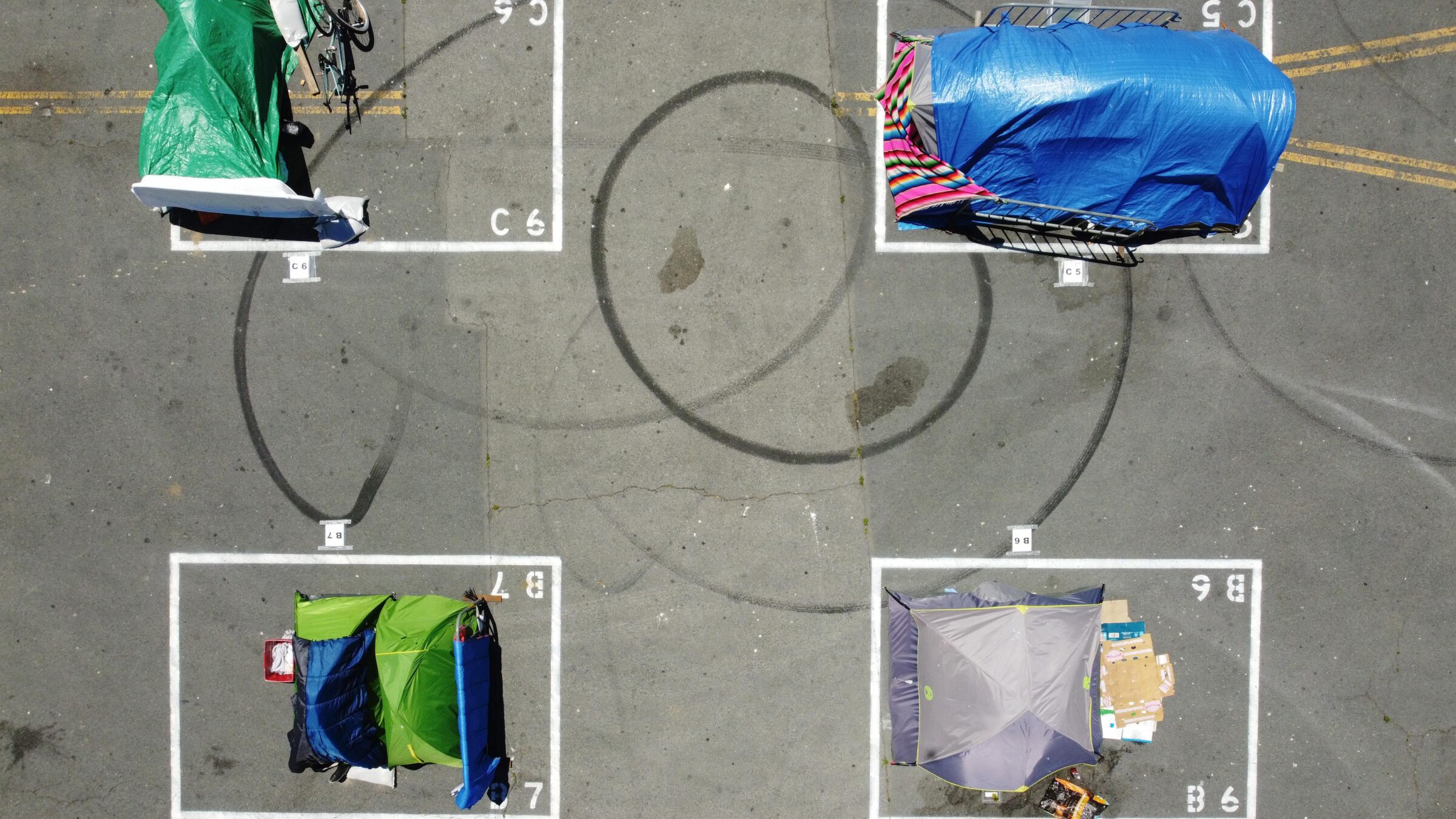

For all the complaining Newsom and company do about Martin-induced policymaking paralysis, Martin gets results that lawmakers and executives do not. Studies show that anti-camping laws do not move unhoused people into shelter so much as they force unhoused people to become transient, cycling through neighborhoods, trying to remain a step ahead of whichever law enforcement agency has the jurisdiction to make arrests. Meanwhile, as the law professor Jeffrey Seblin points out in Cal Matters, in 2021, a federal court ordered the city of Chico, California, to provide shelter to its unhoused residents that included a roof, walls, water, and electricity. (Access to a bare asphalt tarmac, the court ruled in a brazen bit of judicial activism, was insufficient.) Chico officials were furious; they also built 177 tiny homes a year later.

I don’t think anyone thinks that Martin is the best way of addressing homelessness, let alone solving it. But the modest protections the decision extends to people with nowhere but outside to go are far preferable to empowering cities to outsource their homelessness policy to the criminal legal system. Martin is best understood not as an unwarranted incursion on executive authority, but as a last-ditch attempt to shield some of the country’s most vulnerable people from the consequences of their lack of political power—an acknowledgement of basic human dignity that elected officials would otherwise happily ignore. As the challengers to the Grants Pass law put it, when every West Coast city is in the throes of a reactionary anti-tent hysteria, elected officials will inevitably find it “easier to blame the courts than to take responsibility for finding a solution.”

The Supreme Court has a long, bipartisan history of not giving a shit about poor people, and a Court helmed by Clarence Thomas and Sam Alito is unlikely to feel differently. But overturning Martin and cases like it, thus re-empowering cops to harass people dozing on park benches, will only relieve wealthy homeowners of the burden of occasionally confronting the consequences of income inequality on their morning commutes. This result won’t make people any less poor, hungry, or hopeless. It will just let elected officials off the hook.