On the campaign trail in February 2020, Joe Biden made a promise to voters: If elected, he’d nominate a Black woman to the Supreme Court. He reiterated that “long overdue” promise again last week during his remarks at Justice Stephen Breyer’s retirement announcement. “The person I will nominate will be someone of extraordinary qualifications, character, experience, and integrity,” he said. “And that person will be the first Black woman ever nominated to the United States Supreme Court.”

Since then, many conservative pundits have suggested that Biden’s preemptive pledge casts a permanent shadow on the eventual nominee. The Wall Street Journal editorial board called Biden’s promise “unfortunate” because it “elevates skin color over qualifications.” Also at the WSJ, law professor Jonathan Turley bemoaned the implication that the next justice was “qualified by virtue of filling a quota.” The National Review editorial board claimed that Biden had “unwisely limited his options” and had “disqualified dozens of liberal and progressive jurists for no reason other than their race and gender.” Ilya Shapiro, a Cato Institute executive and recent Georgetown University Law Center hire, wrote in a now-deleted tweet that Biden’s nominee “will always have an asterisk attached.”

This is hardly the first time that conservative commentators, perpetually critical of affirmative action for everyone other than conservative lawyers and legacy applicants, have leaped to conclusions like these. After President Barack Obama nominated Sonia Sotomayor to the Court in 2009, for example, Shapiro claimed that Sotomayor “would not have even been on the short list if she were not Hispanic,” and was “not one of the leading lights of the federal judiciary.” As Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern note in Slate, Obama had said nothing publicly about wanting a Latina nominee; pundits like Shapiro simply assumed race was the sole reason for her nomination.

Given the visibility of such bad-faith criticism, some commentators suggested that Biden might have made a tactical mistake, if not a substantive one. In The Washington Post, Ruth Marcus criticized these conservative attacks, detailing the long, bipartisan history of demographic considerations in judicial politics and emphasizing the relevance of lived experience in judicial outcomes. Still, she wrote that she would “be more comfortable if Biden hadn’t been quite so explicit,” since it “carries an aura of unfairness to announce that no one will be considered who does not meet an announced racial test.”

It’s an understandable response. But focusing on the conservative spin on Biden’s promise risks missing the simpler point that presidents—or anyone in a leadership position, really—should incorporate intentional policies around race, gender, and other aspects of lived experience in their selection and hiring processes. Factors like these are inevitably tied up in the way that judges perceive the world and issue their rulings. A legal system cannot be fair if its most powerful actors do not reflect the experiences of the people whose lives their decisions affect.

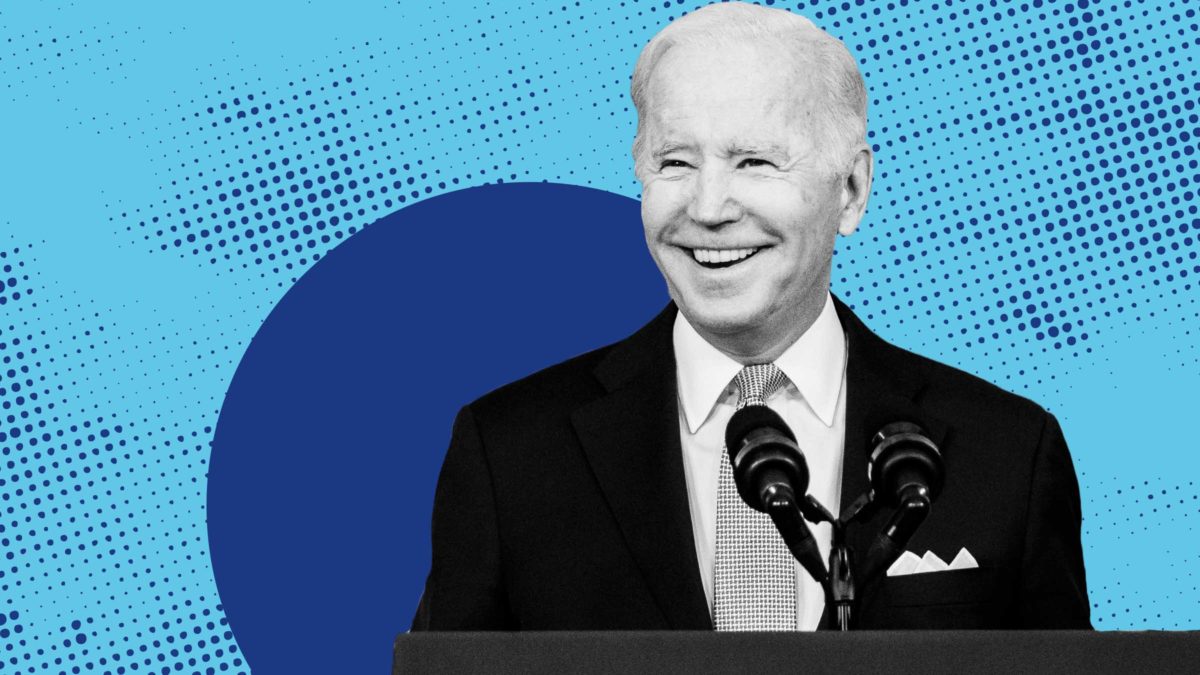

Justice Sonia Sotomayor swears in Joe Biden for a second term as Vice President in 2013 (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Surrendering to conservative framing around race-conscious policies loses sight of the reason these policies exist in the first place. Women and people of color have been structurally excluded from the judiciary for most of its history. It wasn’t until 1934 that President Franklin Roosevelt appointed the first woman, Florence E. Allen, to be an Article III federal judge. It would take several decades more and the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement for President John F. Kennedy to appoint Reynaldo Garza, in 1961, to a federal district court judgeship—the first Latinx person to serve in that role. It would take five more years for President Lyndon Johnson to appoint the first Black woman, Constance Baker-Motley, to serve as a federal judge. Baker-Motley began her judgeship just a year after passage of the federal Voting Rights Act. To this day, people of color are underrepresented throughout the legal profession. While the U.S. is nearly 20 percent Hispanic, for example, just five percent of lawyers are Hispanic.

Meaningfully addressing the bigotry and discrimination that caused this exclusion requires addressing it frankly, not whispering ashamedly about it. Sotomayor put it best in a 2014 dissent: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race,” she wrote, and to acknowledge “the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

Too often, people on the left give themselves a pass from inspecting their own behavior, assuming that alignment of their politics and actions is inevitable. Biden’s explicit promise to pick a Black woman Supreme Court justice sends a message to voters that he takes this responsibility seriously, instead of hiding behind platitudes about “diversity” that he could conveniently forget once the election is over.

Besides, as Marcus noted, denigrations of a nominee—including dim-bulb racist ones—are “inevitable in any event.” And this is why liberals and progressives should not capitulate to pundits arguing that race-conscious policies will negatively impact the qualifications of a nominee. In fact, every Black woman on Biden’s shortlist has sterling credentials, a fact that even Turley, in the WSJ, had to acknowledge; the frontrunners, he writes, “are all worthy candidates who could have been considered for any vacancy.” And because these potential nominees accomplished these things as Black women in an anti-Black society, they are necessarily exceptional and extraordinary. Using race-conscious policies and selecting excellent candidates are not mutually exclusive, despite what Fox News might want you to believe.