On Tuesday, the Senate Judiciary Committee held the second day of confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson. Of the three scheduled days of Jackson’s testimony, this was set to be the longest and most arduous: Each of the Committee’s 22 senators received a half-hour to ask questions, which is 29 minutes and 30 seconds longer than any one human being should be required to hear Lindsey Graham speak. Between lunch, bathroom breaks, vote interruptions, and occasional periods of senators sniping at one another about some inane drama involving paperwork, a hearing that kicked off at 9am concluded well past most of these elderly lawmakers’ bedtimes.

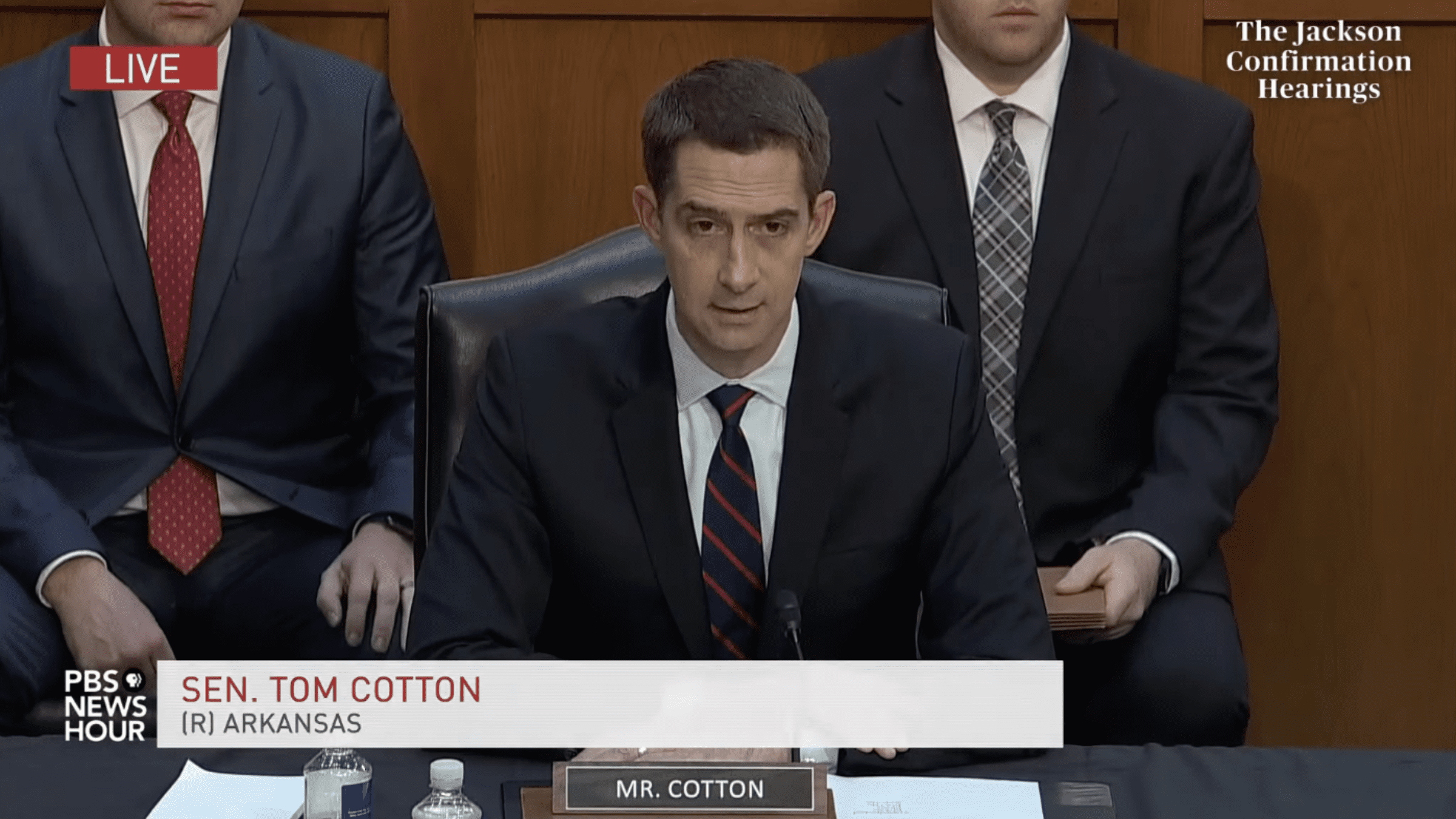

Thus far, Jackson hasn’t professed allegiance to a particular judicial philosophy that would make for a good news soundbite, let alone open her up to meaningful critique. As a result, several Republicans decided to abandon anything resembling a coherent line of questioning and instead spent their time rattling off as many Fox News buzzwords as possible before the horn sounded. With the 2024 presidential primary looming, Missouri’s Josh Hawley, Texas’s Ted Cruz, and Arkansas’s Tom Cotton saw Jackson’s hearing as a free opportunity to win some votes from the January 6th insurrection crowd, and did not pass it up.

“Judge, I’d like to talk about crime,” Cotton barked, as if stepping out of a time machine from Richard Nixon’s speech announcing the War on Drugs. He began his tirade by warning of “record levels of murder” in Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and Atlanta before proceeding to a series of bizarre this-or-that policy questions, including “Does the United States need more or fewer police?”, and “Is 17 years too long or not long enough for criminals to spend in prison for murder?”, and “Do you think we should catch and imprison more murderers or fewer murderers?”

Clip via YouTube

With each question, Jackson patiently explained why separation-of-powers principles and limits on judicial authority mean that Cotton’s questions would be better directed to the legislature—the branch of which, incidentally, Cotton is a member. “These are policy questions,” she said. “Whether they’re in the province of the Sentencing Commission in terms of recommendations, or whether they are in Congress, they’re not the kinds of things I can opine about.”

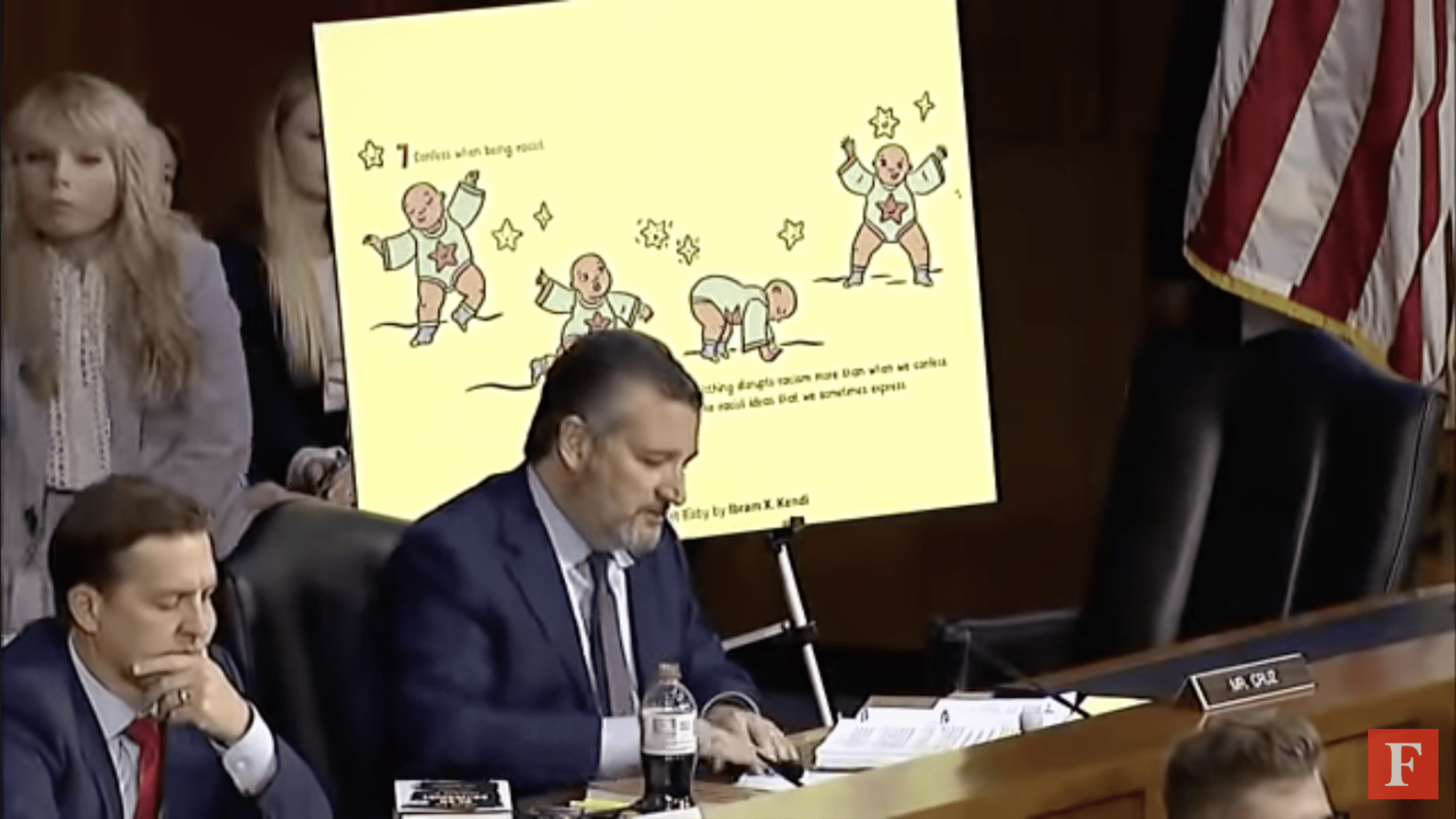

Cruz, meanwhile, made critical race theory his culture war of choice. He also brought visual aids, blowing up images of children’s books that appear on the suggested reading list of a local private school where Jackson serves on the board. “If you look at the Georgetown Day School’s curriculum,” he warned, “it is filled and overflowing with critical race theory.”

When you’re speaking truth to power (Photo by JIM WATSON/AFP via Getty Images)

Among the titles that made Ted Cruz’s stress veins pop are Critical Race Theory: An Introduction by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, and The End of Policing by Alex Vitale. But it was Ibram X. Kendi’s books, How to Be An Anti-Racist and Antiracist Baby, that truly enflamed Cruz. “Do you agree with this book—that the babies are racist?”, he asked. Jackson reminded Cruz that as a board member, she has no input on the curriculum or suggested reading lists, none of which was enough to deter a sitting U.S. senator from getting very upset about cartoons in public.

Clip via YouTube

Hawley remained committed to harping on the sentences of people convicted of child pornography offenses. For a painfully long amount of time, he discussed the details of the child pornography at issue in U.S. v. Hawkins, a case Jackson adjudicated as a district court judge. He admonished her for sentencing the defendant—an 18-year-old who had recently graduated from high school—to three months in federal prison, a result that he suggested dismissed the interests of the victims of child pornography entirely. “I am questioning your judgment, and I am questioning your discretion,” he said. “That’s exactly what I’m doing.”

Jackson, who by now must be very used to Hawley’s objectively wrong and unsettlingly Pizzagate-adjacent lines of inquiry, explained that Congress requires judges to impose sentences “sufficient but not greater than necessary to obtain the goals of punishment,” and that sentencing is not merely a “numbers game.” Hawley, a Yale Law School graduate, former Supreme Court clerk, and former state attorney general, is perfectly capable of understanding how this process works, but he also knows the people who book guests for Tucker Carlson’s A-block are not, and that’s the only constituency that really matters to him.

Theatrical though they were, none of these attacks seemed to accomplish much, other than making everyone in the room some combination of uncomfortable and confused. On Wednesday, Jackson will face each Senate Judiciary Committee member for an additional 20 minutes of questioning; when that leg of the race is over, her time before the senators will finally, mercifully be over, too. There is little reason to think tomorrow will be any less unhinged. But if a full day of Republicans’ furious broadsides couldn’t shake Jackson’s poise, there is little reason to think she’ll handle things any differently.