The latest self-inflicted blow to the Supreme Court’s reputation as a wise and principled protector of constitutional rights comes at the cost of a man’s life. The facts of Thomas v. Lumpkin are stunning, but the Supreme Court refused to hear them: Instead, its conservative supermajority issued an unsigned order on October 11 denying Andre Thomas’s petition for review of his capital case. This judicial equivalent of leaving you on read means that the lower court’s ruling will stand by way of the Court’s inaction. The local district attorney’s office is already pursuing a date for Andre’s execution.

Andre Thomas, a Black man, killed his estranged white wife, their biracial child, and her child from a previous relationship in 2004, while he was suffering from severe schizophrenia and active psychosis. He then attempted to kill himself, but survived and turned himself in to the police. While awaiting trial in state custody days later, Andre took the Bible’s guidance—“if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out”—quite literally and gouged out one of his eyes. The prosecution’s expert at first agreed that he wasn’t competent to stand trial. But after five weeks at a psychiatric facility, where two doctors asserted that cold medicine “exaggerated” his psychosis, Andre’s trial began; he pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. He was convicted and sentenced to death in 2008, after which he removed and ate his other eyeball.

That death sentence was handed down by an all-white jury, three members of which openly expressed racist views directly relevant to Andre’s case during jury selection. One indicated that he “vigorously” opposed interracial marriage and people of different racial backgrounds having children and was “not afraid to say so,” explaining, “I don’t believe God intended for this.” Another opined that “we should stay with our Blood Line” and expressed his faith’s position is that interracial relationships “should not be”; still another stated that interracial relationships are “harmful for the children involved because they do not have a specific race to belong to.”

The attorneys representing Andre could have challenged those jurors “for cause”—a method of disqualifying potential jurors who wouldn’t be capable of deciding the case fairly. They did not do so. They could have used peremptory strikes, which allow lawyers to dismiss a juror without giving a reason. They didn’t do that either. They could have asked the jurors whether their bias would impact their ability to consider mitigating evidence—circumstances that don’t excuse an act, but that provide context that may warrant a less harsh sentence. His attorneys again did nothing.

If these lawyers had a good explanation for their silence, they didn’t share it. “My failure to ask few, if any, follow up questions of the members of the jury who had indicated on their jury questionnaires that they were opposed to interracial marriage was not intentional,” they later admitted in one of Andre’s appeals. ”I simply didn’t do it.”

(CHANTAL VALERY/AFP via Getty Images)

The Court has repeatedly recognized that racial discrimination in the administration of justice undermines the rule of law, and that the Court must be particularly vigilant in capital cases. Half a century ago in Parker v. Gladden, it reminded prosecutors and litigants that defendants are “entitled to be tried by 12, not 9 or even 10, impartial and unprejudiced jurors.” Just one racist juror would have violated Andre’s right to an impartial trial; his jury had three. And the prosecution didn’t shy away from appealing to those biases, either, eliciting irrelevant testimony about other sexual relationships Andre had with white women, and asking the jurors if they were “going to take the risk” of sentencing Andre to life imprisonment with possibility of parole, after which he might date their daughters or granddaughters.

Specialized knowledge of law and precedent is not necessary to understand that it’s unreasonable to seat an all-white jury that includes people who oppose interracial marriage and reproduction to decide a case where a Black man killed his white wife, biracial child, and white stepchild. You simply aren’t well-suited to fairly adjudicate Andre’s fate—including the potentially mitigating evidence of his history of severe mental illness, and the question of whether he should be incarcerated or executed—if you believe his marriage and children were against God.

And to address the crow named Jim in the room, the connections between this grim present and the not-that-distant past are obvious and chilling: White supremacists have historically propagandized Black men and boys as predators deserving punishment for preying on white women. Even imagined acts of violence by Black men against white women have been used as justification to inflict racial terror on Black communities. An effective attorney—and a responsible judge—would have at least tried to prevent racial animus from infecting the jury in a cross-racial murder trial. But Andre’s counsel did not, and now, the Supreme Court has blessed by inaction both the biased jury makeup and the attorneys’ puzzlingly poor lawyering. Apparently, future courts can let racist jurors sentence defendants to death while defense counsel stands idly by.

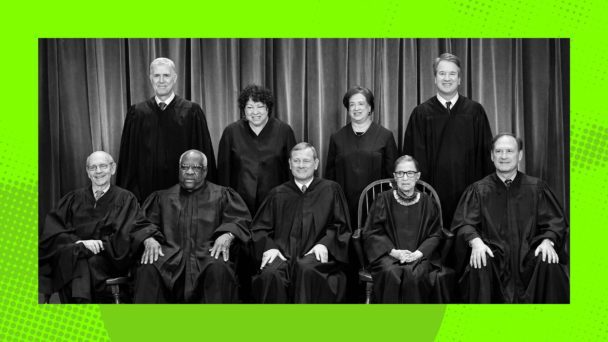

The Court’s failure to even hear this case is a jaw-dropping failure. Personally, I believe the death penalty is moral barbarism in any case, but its imposition in this case specifically also clearly violates the Sixth Amendment rights to an impartial jury and to effective assistance of counsel in criminal cases. This isn’t just my feelings—this is law. Or at least, what law is supposed to be, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in a dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. “No jury deciding whether to recommend a death sentence should be tainted by potential racial biases that could infect its deliberations or decision, particularly where the case involved an interracial crime,” she wrote. Although the dissent exposes the egregiousness of this Court’s failures, it will be no help to Andre Thomas.

The Supreme Court stated decades ago that racism in jury selection “damages both the fact and the perception” of the jury’s role “as a vital check against wrongful exercise of power by the State.” The Court’s disregard of Andre Thomas’s Sixth Amendment rights therefore harms everyone who lives under its rulings. There’s no question that he committed horrific crimes. But sympathy for the victims and the administration of justice are not in conflict; Andre Thomas’s family should be alive, and he should have received the fair trial the Constitution guarantees him. Any shreds of integrity the legal system has left unravel when it abandons such bedrock principles.