Ashtian Barnes was driving a rental car on April 28, 2016, when he went to pick up his girlfriend’s daughter from her daycare in Houston, Texas. He didn’t know that one of the rental car’s previous drivers had accumulated $6.45 in unpaid tolls. Around 2:40 P.M., Sergeant Roberto Felix, Jr., an officer for the Harris County Precinct 5 Constable’s Office, heard a radio broadcast about a “prohibited vehicle” with “outstanding toll violations.” Felix spotted Ashtian’s car and pulled the 24-year-old Black man over a few minutes later.

Felix ordered Ashtian out of the car, at which point Felix claims that Ashtian opened the door but began to drive off. In the next three seconds, Felix jumped on top of the moving vehicle and shot Ashtian twice. Felix continued to hold Ashtian at gunpoint for several more minutes as he lay bleeding. By 2:57 P.M., Ashtian was dead.

The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution prohibits police officers from using “unreasonable” force. But cops and civilians tend to have very different ideas about what reasonable means. The Harris County District Attorney’s Office didn’t indict Felix for killing Ashtian, after it gave a grand jury a police report on the incident and the grand jury returned a finding of no probable cause. The police department also concluded there was no violation of its standard operating procedures. So, in an effort to obtain some kind of accountability, Ashtian’s mother, Janice Hughes Barnes, filed a lawsuit in 2017 arguing that Felix violated her son’s constitutional right to be free from excessive force. But in 2021, the trial court dismissed her case, and an appeals court affirmed the dismissal last year.

Both lower court decisions hinged on how, exactly, courts should assess whether an officer’s use of force is reasonable. That question divides federal judges as much as it divides the police and their victims. On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Ashtian’s mom’s appeal, Barnes v. Felix, to decide if the lower courts used the right standard in his case—or if Janice Hughes Barnes can make the case in court that the cops were wrong to kill her son.

Anaya Barnes, 21, Ashtian Harris, 3, Janice Barnes, 52, and Aledra Barnes, 25, hold a photo of Ashtian Barnes, Monday, Dec. 13, 2021, in Houston. (Marie D. De Jesús/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images)

In eight of the country’s courts of appeals, which collectively hear appeals from 32 states, 4 territories, and the District of Columbia, federal judges evaluating a cop’s use of force review the “totality of the circumstances.” As the word “total” might suggest, this is a fact-intensive inquiry, where courts are able to consider things like how severe the crime at issue was, and whether the suspect posed an immediate threat to the officer or others, and what the officer did in the minutes before their use of deadly force.

But Ashtian wasn’t killed in any of the states applying that standard. He was killed in Texas, where federal trial courts follow a different standard. In the Fifth Circuit and three other circuits, judges instead zoom in on the precise moment when the officer perceives a threat in order to decide whether the use of force was reasonable. Under the “moment of the threat” doctrine, the only relevant consideration is if Felix reasonably believed his life was in danger in the seconds that immediately preceded him firing his gun—that is, when he was already hanging off of a moving car. Whether Felix created that danger himself by pulling Ashtian over for a nonarrestable offense and attempting some stunt out of Fast and Furious doesn’t matter.

The trial court and the appeals court opinions both openly expressed frustration with this standard, and practically begged the Supreme Court to intervene. Judge Patrick Higginbotham, a senior judge on the Fifth Circuit appointed by President Ronald Reagan, wrote the opinion for the three-judge panel, and wrote a separate concurring opinion criticizing the standard he just applied. “The moment of threat doctrine starves the reasonableness analysis by ignoring relevant facts to the expense of life,” said Higginbotham. And since “a routine traffic stop has again ended in the death of an unarmed black man,” he urged the Supreme Court to resolve the circuit split so that a cop who “stepped on the running board of the car and shot Barnes within two seconds, lest he get away with driving his girlfriend’s rental car with an outstanding toll fee,” didn’t evade liability for violating Ashtian’s constitutional rights.

At oral argument on Wednesday, lawyers representing Felix and the state of Texas argued that the lower courts did evaluate the totality of the circumstances, and it’s just that everything preceding the moment of the threat—including whether the officer created the danger to begin with—is not a “relevant circumstance.” This argument did not fare well.

“Totality of the circumstances were not used by this court, correct, in this opinion?” Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked. “It was,” Felix’s attorney replied. Sotomayor, annoyed, asked whether he could “point…to a place in the opinion where it used the words ‘totality of the circumstances.’” Felix’s attorney replied, “I cannot.”

Later, Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson and Elena Kagan emphasized that Felix’s counsel was conflating the question of how heavily judges should weigh an officer’s earlier conduct with the question of whether judges are allowed to weigh that conduct at all. “It seems as though the moment of the threat doctrine, as it exists and as everybody has understood it, is about evidence, essentially. It’s, ‘What can you look at to prove the alleged Fourth Amendment excessive force claim?’” said Jackson. She continued, “You seem to be now suggesting that it is about liability”—in other words, permission to look at all the facts is not the same as a conclusion that the facts prove guilt. Kagan also observed that “the question of what weight to give the fact that or the possibility that the officer created the danger in the reasonableness inquiry” is “definitely not the question in this case.”

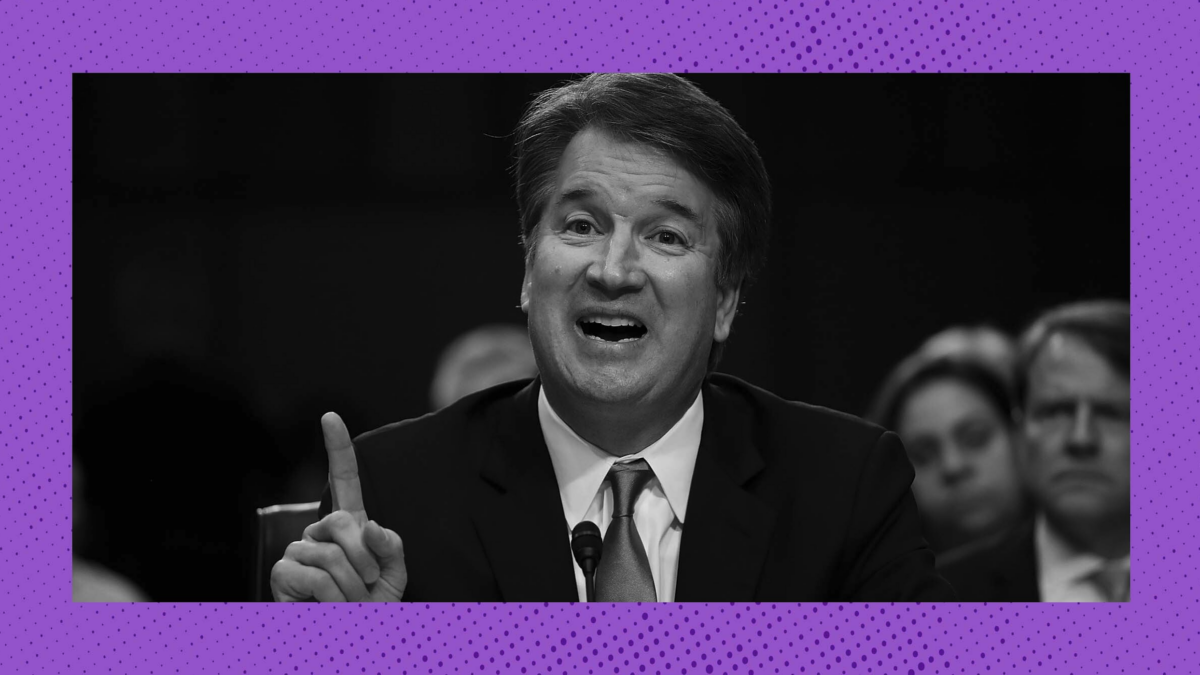

Only Justice Brett Kavanaugh implored his colleagues to think of the armed agents of the state who risk their lives every day to kill Black people at unnecessary traffic stops. “Are officers always prohibited at traffic stops, when the car pulls away, from jumping on the car?” he asked. “Traffic stops sometimes identify people who are doing things that are much worse. Oftentimes, major criminals are apprehended for things like that.” He worried that moving away from the moment of threat doctrine would force officers to choose between letting go of a moving car, “knowing that this person could do serious harm,” or, as Felix did, jumping on the hood and seeing what happens.

Kavanaugh, like counsel for Felix and Texas, fretted over the possibility that judges and juries would too often second-guess police officers’ split-second decisions, and hold them liable in all cases where they use force. The reality is much more modest: The totality of the circumstances standard would merely allow more survivors—or decedents’ loved ones—to make a case in the first place. The legal system has not yet recognized that Black lives matter, but Barnes v. Felix can at least acknowledge that more matters than the singular perspective of a cop at the exact millisecond they felt afraid.