A little before sunrise on August 21, José Escobar Molina pulled on his work clothes, walked out of his apartment in Washington, D.C., and headed towards his work truck so he could go to his job as a scaffolder. Two unmarked vehicles pulled up beside him. Four men got out: Two of them grabbed Molina’s arms and handcuffed him while the other two grabbed his legs. Together, they forced Molina into a black Suburban.

The men didn’t say who they were, or ask Molina who he was. Molina, who was born in El Salvador and obtained temporary protected status from the U.S government in 2001, told them that he “had papers,” correctly guessing that the men abducting him were law enforcement officers. “No you don’t,” the officers responded. “Shut up, bitch!” one said. “You’re illegal.”

Molina was first taken to a parking lot near the Pentagon, and then shuttled to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Chantilly, Virginia. Around 1 PM, officers obtained a copy of Molina’s work permit, which proved his lawful presence in the country, but they held him overnight anyway in a cell with dozens of other people, without room to lie down and sleep. The next morning, a supervising officer apologized, gave Molina a copy of his papers—recommending he carry them in case he’s stopped again—and told him he was free to go. His ordeal lasted roughly 23 hours.

A few weeks later, Molina and three other noncitizens with pending immigration applications sued the Trump administration in federal district court in Washington, D.C. By law, in order to make an immigration arrest, federal agents need to either have a warrant, or probable cause to believe a person is in the country unlawfully and will escape before they can get a warrant. In their lawsuit, Molina and the others asked the court to block the administration from making additional warrantless arrests without that probable cause. And on Tuesday, in Molina v. Department of Homeland Security, Judge Beryl Howell granted their request.

The Trump administration made several arguments as to why the judge should toss Molina’s case, including pointing to Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, the Supreme Court’s recent order that lifted a lower court injunction blocking immigration officers from stopping people solely because of their presumed race, their location, and whether they speak Spanish or accented English. But Howell rejected the idea that Vasquez Perdomo was relevant or persuasive, since the issues in Molina are distinct from those in Vasquez Perdomo. Howell also reasoned that, as a four-sentence, unreasoned shadow docket order, Vasquez Perdomo didn’t have much value as precedent.

“The Court majority merely issued a one paragraph order granting a stay without any explanation for its holding,” she said. “Bluntly put, why the Court ruled as it did remains unclear—and without reasoning, this order cannot even be considered as persuasive.”

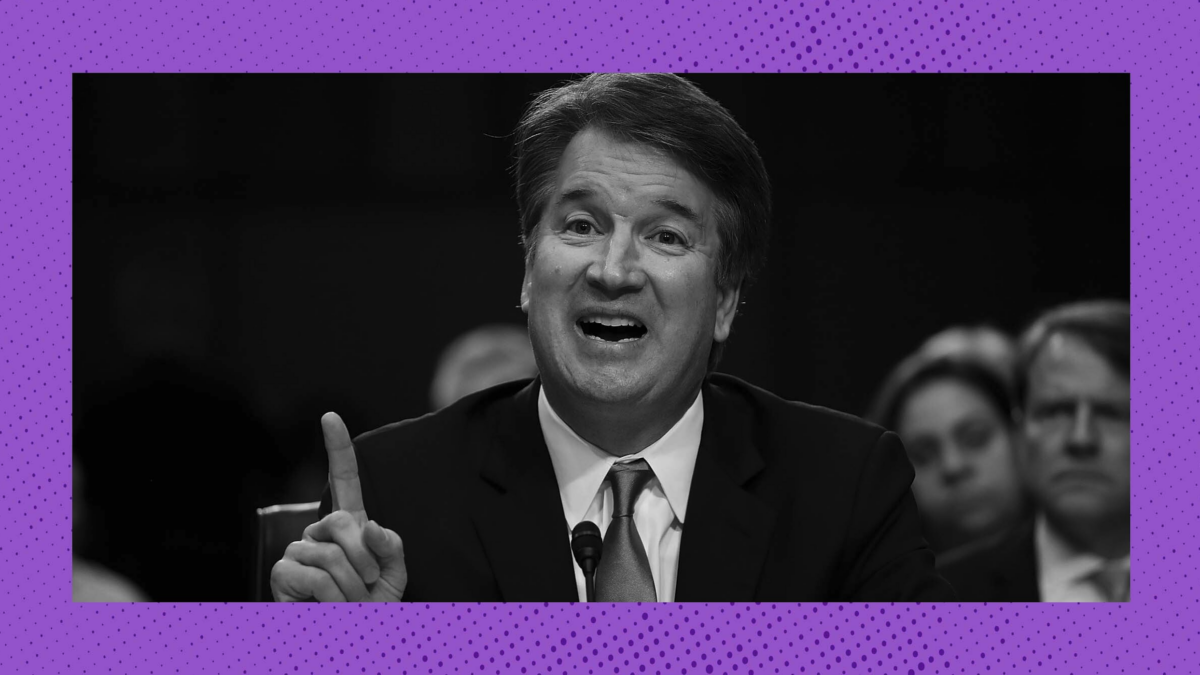

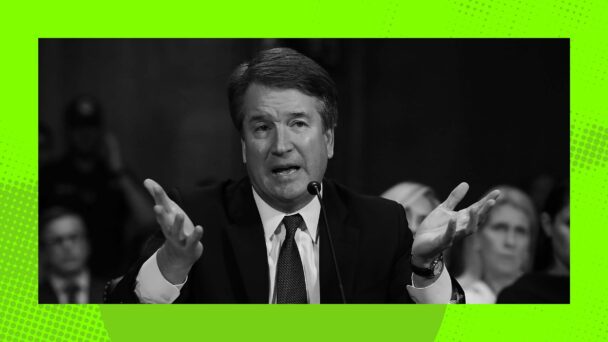

Justice Brett Kavanaugh did write a solo concurrence in Vasquez Perdomo, in which he infamously claimed that people who had been racially profiled by immigration agents likely lacked standing to bring their case in federal court because they were unlikely to be racially profiled again. “Plaintiffs have no good basis to believe that law enforcement will unlawfully stop them in the future based on the prohibited factors—and certainly no good basis for believing that any stop of the plaintiffs is imminent,” he wrote.

Although Kavanaugh wrote only for himself, the Trump administration invoked his concurrence in its briefing to argue that Molina lacked standing. But Howell was having none of it. First of all, Howell explained, Kavanaugh was just plain wrong: The plaintiffs here provided plenty of evidence showing that they “cannot avoid run-ins with these agents lest they avoid going about daily life.”

Second, Howell explained, the plaintiffs in Vasquez Perdomo argued that the government wrongly used race as a factor in their application of a legal standard for immigration stops. Here, in contrast, the plaintiffs “contend that defendants have abandoned the proper legal standard entirely,” and instituted an “arrest first, ask questions later” policy instead. In October, Chief Border Patrol Agent Gregory Bovino told the press as much, explaining that agents use—and only need to use—“reasonable suspicion of illegal alienage” to make immigration arrests.

Basically, in Vasquez Perdomo, Kavanaugh said that race can be a relevant factor in establishing probable cause for an immigration stop. But here, the government argued that probable cause is irrelevant, and that they can arrest anyone they feel like. “Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence in Vasquez Perdomo, to the extent it has persuasive, let alone controlling, authority, is inapposite,” said Howell.

Howell’s opinion is at least the second sign in recent weeks that lower court judges are learning how to navigate some of the Supreme Court’s shadow docket orders. Last month, a federal judge in Massachusetts denied the Trump administration’s motion to dismiss a challenge to its mass cancellation of Department of Education grants. The government argued that the logic of one of the Court’s recent shadow docket orders compelled dismissal, but Judge Angel Kelley declined the government’s invitation to follow the Supreme Court’s lead. “Not all Supreme Court writings are equal,” she said.

In theory, Supreme Court decisions should provide guidance for the lower courts. Yet the Supreme Court keeps making decisions that hurt people without bothering to explain itself. And without the guidance, lower courts have more freedom to chart their own course.