Whenever one of William Brennan’s law clerks would come to his chambers to vent about a Supreme Court decision they found unconscionable, the justice would simply remind them how arithmetic works. As Nan Hentoff recounted in a New Yorker profile of Brennan, the staunch liberal who stepped down in 1990 at age 84: “Brennan holds up his hand, wriggles his five fingers, and says, ‘Five votes. Five votes can do anything around here.’”

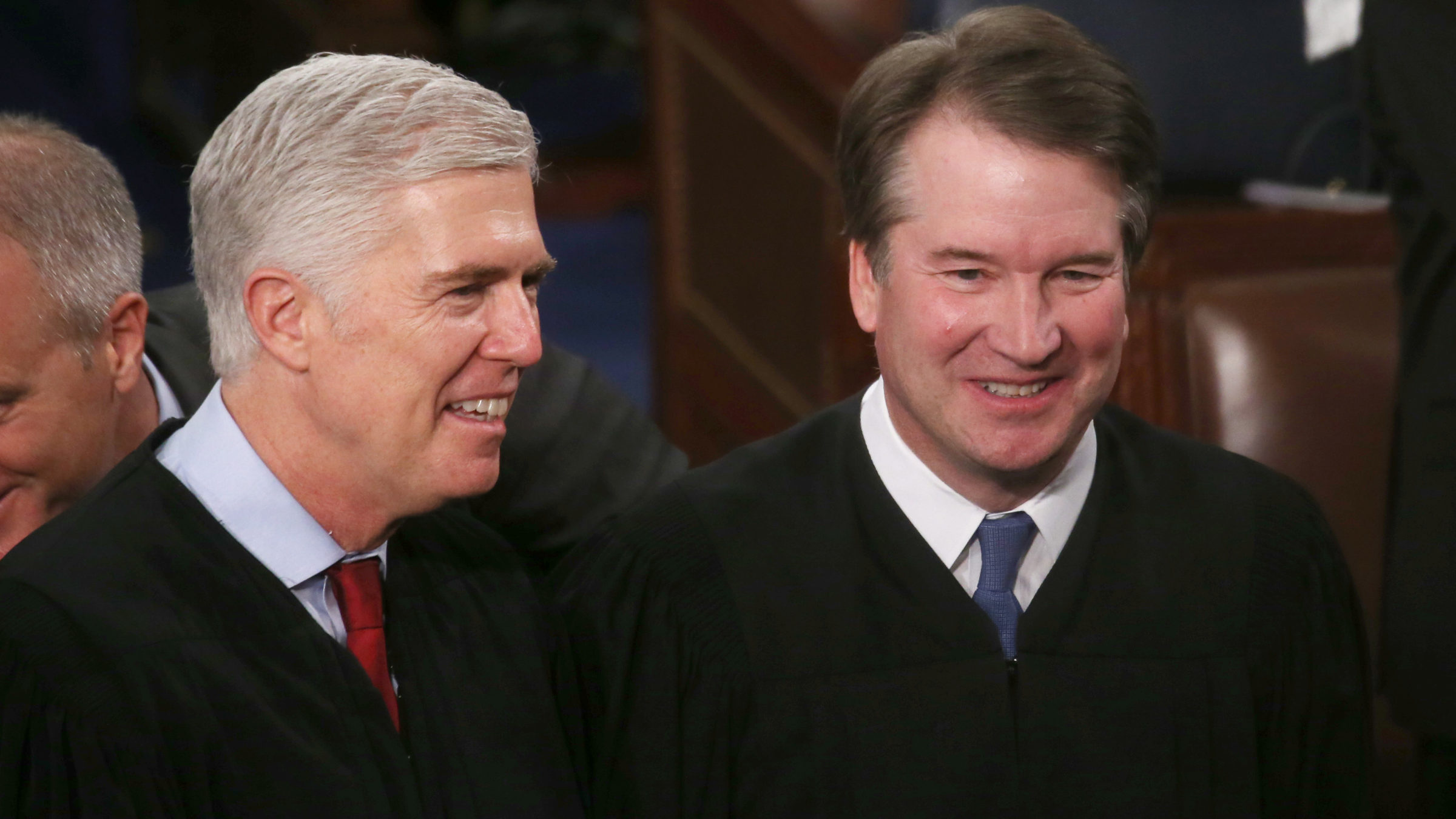

Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh would have missed the last live rendition of this “Rule of Five” speech; both of them clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy from 1991 to 1992, a year after Brennan’s retirement. But the Court’s majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overrules Roe v. Wade and ends five decades of constitutional protections for the right to abortion care, makes clear that they absorbed this lesson anyway.

Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the opinion, spills plenty of ink to explain the intellectual underpinnings of his decision. The dissent strains just as diligently to explain why it is wrong. All of it is jurisprudential dressing on an easy counting exercise: A 6-3 conservative supermajority has more than enough votes to do whatever it wants. Thanks to a tangle of “trigger laws,” pre-Roe abortion bans, and pending legislation to which Dobbs gives the green light, abortion will be illegal in more than a dozen states by Labor Day. In a handful of states with especially ambitious Republican leadership, abortion will be illegal by the time you read this sentence.

(Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images)

Friday’s opinion in Dobbs is nearly identical to Alito’s caustic, triumphant draft opinion that leaked in May. Other than two sections that address the joint dissent from Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elana Kagan, and another that takes on Chief Justice John Roberts’s feeble attempt to weaken Roe while preserving a husk of it, the final version basically picks up where the draft left off. One of Alito’s colleagues did persuade him to remove the spiking-the-football “Zero. None” language that originally followed this sentence: “Until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion.” Striking smug kickers from rights-eviscerating opinions is what passes for moderation on today’s Court; somewhere, Susan Collins is smiling proudly.

That nothing about Dobbs changed in the past three months is not a surprise, because nothing about the anti-choice movement has changed over the past fifty years. None of Alito’s arguments would have been out of place in the chorus of law review articles, ambitious state abortion bans, and Republican National Convention speeches that have called steadily for Roe’s death. The Constitution’s text does not protect abortion. Such a right would have been unthinkable to the Framers, and to the centuries of English common law that preceded them. Our conception of “ordered liberty” tasks elected officials, not judges, with deciding who controls the bodies of pregnant people. And so on. Every note of Dobbs is familiar; the only difference is that for the first time, there are five justices willing to put their names to it.

The majority’s attempts to identify some changed circumstance on which to hang their hat are cursory and half-hearted at best. The notion, for example, that abortion access is no longer important because “safe haven” laws mean that many women can legally abandon their infants at fire stations now is the sort of argument that was previously persuasive only to National Review backbenchers, and is now getting cited approvingly by the U.S. Supreme Court. The dissenters’ response to this silliness is equal parts unsparing and despairing: “Neither law nor facts nor attitudes have provided any new reasons to reach a different result than Roe and Casey did,” they write. “All that has changed is this Court.”

It is rare to see justices call out the role of the Court’s evolving membership like this, because the most sacred shibboleth of American legal culture, and particularly for liberal lawyers, is that law and policy are distinct. For once, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan abandon this tradition, excoriating the majority for not even bothering to cloak its reactionary agenda beneath a layer of polite-sounding legalese. Oddly, a sense of the sheer inevitability of the outcome in Dobbs permeates both opinions: The majority recites the same talking points these justices have spent their entire careers memorizing, while the three liberals seem to realize that there is no longer any point in holding their collective tongue.

“The majority has overruled Roe and Casey for one and only one reason,” they write. “It has always despised them, and now it has the votes to discard them.”

For the conservative legal movement, overturning Roe is the product of a decades-long, wildly successful effort to stock the bench with right-wing judges. This cake was baked in October 2020, when the Republican-controlled Senate replaced the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg with Amy Coney Barrett days before the president who nominated her lost his bid for reelection. It was baked in 2018, when Justice Anthony Kennedy, whose 1992 vote in Planned Parenthood v. Casey gave Roe a 30-year reprieve, stepped down from the Court, eventually yielding to Kavanaugh, his former clerk. It was baked in 2016, when Senate Republicans held open Justice Antonin Scalia’s vacant seat for nearly a full year, denying the liberals a solid majority and allowing Trump to appoint Gorsuch as his successor.

(Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Conservatives caught some breaks along the way, too. This cake was also baked in 2013, when Ginsburg, then 80, ignored calls for her to retire so that President Barack Obama and a rapidly-eroding Democratic Senate majority could confirm a pro-choice replacement. Ginsburg, of course, wanted someone who would preserve the progress for which she’d fought her entire career; she also really, really liked her job. Her decision to stay on the bench was a massive gamble on both her failing health and also on this country’s failing democracy. Today, it is indisputable that she lost the bet.

The right will take a victory lap for Dobbs, but the judicial counterrevolution it portends is just getting started. Dobbs pushes other bedrock civil rights protected by Supreme Court precedent—marriage equality, contraceptive access, sexual privacy, and so on—further out onto constitutional thin ice. Alito, and Kavanaugh in his concurrence, pinky-swear they aren’t coming for those decisions next. But nothing about the logic of Dobbs limits its applicability to abortion. Believing that this conservative supermajority will unilaterally stand down at the apex of its power requires trusting Sam Alito to tell the truth, and Brett Kavanaugh, of all people, to keep a promise. Ask Susan Collins about that.

In the fifty years since Roe, the conservative legal movement has sought to build a Court in its own image—a majority of justices who will not be swayed when a critical New York Times column gets them left off a cocktail party invite list. Today, finally, they got to five. Already, fringe groups are making the case for which civil right this Court should dispose of next, and one fringe justice, Clarence Thomas, is pining for the chance to do so. The only remaining questions are how quickly these activists can get test cases before the Court, and how soon Thomas can persuade his colleagues to take the plunge. William Brennan was always right: With five votes, you can do anything around here.